Following an unusually quiet December for the Russian president, Vladimir Putin has emerged to deliver his traditional New Year’s Eve address. The first since his invasion of Ukraine ten months ago, many across Russia’s eleven time zones will today be glued to TV screens and internet live-streams at five minutes to midnight to hear what he has to say. With 2023 already beginning in half of those time zones, we too have been able to view his speech.

In years gone past, Putin’s typically predictable and formulaic pre-recorded New Year’s Eve speech has been a staple fixture of Russia’s countdown to midnight. It is a useful touchstone for Putin and the Kremlin to feign a connection with the Russian people. This year’s speech has shown itself to be a complete departure from precedent.

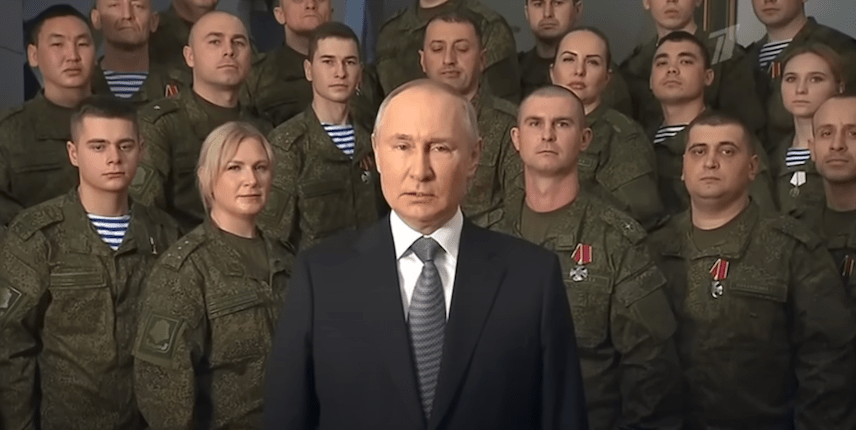

From the very beginning, it was obvious what the theme of Putin’s speech would be. Instead of posing against his usual Kremlin backdrop, Putin delivered today’s address flanked by 20 morose-looking Russian servicemen and women, all clad in army fatigues, with several sporting medals.

In previous years, the President’s speech has followed the same rough formula: speaking for a maximum of five or so minutes, Putin touches vaguely on the trials and tribulations the outgoing year has brought, ending it with a call to action for Russians to unite, love each other and go into the new year on a fresh slate. Heartwarming stuff.

Conforming to a pattern that has become recognisable in the many speeches Putin has given since invading Ukraine in February, what emerged today though was an aggressive, ranting address to the nation. At over nine minutes long, it is the longest New Year’s Eve address he has ever given.

Although immediately different in tone, the beginning of Putin’s speech began much the same. Using a phrase employed annually with such predictability it has spawned memes and satire, this year, Putin said, has been ‘a difficult one’. Here, however, the similarity to previous years ended.

At first, his references were jingoistic but vague: this year, he said, ‘clearly separated courage and heroism from betrayal and cowardice. It showed there is no higher power than love for one’s nearest and dearest, loyalty to friends and comrades, devotion to one’s Fatherland.’

But very quickly, Putin reverted to themes common to his speeches in recent months. Referencing Donetsk, Kherson, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia, the Ukrainian regions annexed by Russia in September, Putin said: ‘This is what we are fighting for today. We are protecting our people in what are our historic territories and who are the newest subjects of the Russian Federation.’ ‘Moral historical correctness’ – Putin’s fictitious justification for the invasion – ‘is on our side’, he declared.

Slipping into the realms of conspiracy the Kremlin has been peddling for most of the year, Putin continued: ‘For years, the Western elites have hypocritically assured us all of their peaceful intentions.’ Instead, he said, they had ‘encouraged neo-Nazis in the Donbass’. It was the West, and not Russia, which ‘lied about peace but was preparing for aggression’.

In rhetoric representative of the alternative narrative Putin’s regime has been spinning regarding the war, he accused the collective West of being the aggressor in Ukraine: ‘They are cynically using Ukraine and its people to weaken and divide Russia. We have never allowed anyone to do this, and never will.’

The West’s ‘sanctions war’ on Russia has failed, he said; the country’s industry, finances and transport have not been destroyed. Gallingly Putin continued: ‘Our fight for ourselves, our interests and our future of course serves as an inspiring example to other states striving for a just, multipolar world order.’

Putin then addressed those on the front line, thanking soldiers and key workers alike for their service: ‘There are sure to be many toasts in your honour at the New Year’s table tonight.’ The families of any fallen servicemen would be taken care of, he promised.

Speaking to Russians more broadly, Putin alluded to their supposed unity: ‘I want to thank you for your sensitivity, responsibility and kindness. For the fact that you, people of different ages and wealth, are actively involved in the common cause.’ Chillingly, referencing Ukrainian children, many of whom have been proven to have been forcibly separated from their parents and transported to Russia, he thanked Russians for ‘sending children from the new regions of the Russian Federation on holiday’.

Following months of humiliating setbacks, Russia’s military campaign has proven increasingly difficult for Moscow to sell to the Russian people this autumn and winter. The Kremlin will be watching the response to Putin’s speech, and this part in particular, to see whether it has any success in assuaging public sentiment over the coming days and weeks.

In the final few minutes of his address, Putin jarringly strove to draw people’s minds back to fuzzier, warmer images of the holiday season: ‘Meeting the new year, everyone tries to bring happiness to those closest to them, to warm them with attention and affection from the heart, to give them the presents they wished for.’

Rounding off his speech with a strange call to action that combined jingoistic nationalism with festive merriment, he said: ‘Together we will overcome all difficulties and keep our country great and independent, we will go forth and win for the sake of our families and Russia, for the sake of our only, beloved motherland’s future.’

A legacy of the Soviet Union’s atheist past, New Year’s Eve is considered a particularly important celebration in Russia. Rituals more commonly associated with Christmas in Europe, such as exchanging gifts (including Santa Claus visiting children with presents) and gathering together for a meal, instead take place tonight. Russians treat the occasion as a family holiday; Moscow’s famous kitsch, hedonistic variety show (surreally, incidentally, presented exactly ten years ago by none other than Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky during his time as a comedian, before his entry into politics) is beamed into nearly every living room in the country.

It is difficult to understate how, even to Russians by now acclimatised to the Kremlin’s ranting propaganda, the aggressive, almost paranoid nature of Putin’s speech will feel out of kilt with the festive mood of the season. The change in tone of his message will not have gone unnoticed.

Putin’s wish for 2023 is clearly a united Russian victory in Ukraine. Whether the Russian people, after global isolation, economic hardship, military defeats and thousands of war dead, agree to rally to his call remains to be seen. This year, as the Kremlin’s ‘special military operation’ has faltered, Putin’s speeches have given way from justifying the war as a quest for shared nationhood to an existential war against the West.

Comments