Youth unemployment is approaching crisis levels in Britain. For almost two decades, Britain’s more flexible labour market had favourable effects on youth employment. But the re-regulation of the British economy has narrowed the difference between our jobs market, and that of the continent. Meanwhile the British poverty trap has been strengthened by a dysfunctional welfare state: British workers can in some circumstances keep as little as 5p in every extra pound they earn if they find work. Who would break their back for less than 50p an hour? We’re paying people not to bother, so little wonder that most of the employment rise — in the last government, and under this one — is accounted for by a rise in foreign-born workers. A third factor: minimum wage for young people is also set at a rate above that normally judged harmful to employment prospects, as Tim Worstall has pointed out.

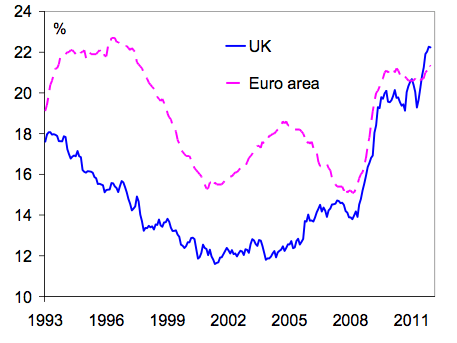

Net result? Our youth unemployment is now even worse than that of the Eurozone, as the below graph from Citi shows:

Michael Saunders, whose analysis we often cite on Coffee House, draws this conclusion:

I’m not saying that ‘foreigners are taking our jobs’ — just that if you pay people not to work, as the British welfare state continues to do, then they’ll take you up on your offer. (The IDS reforms are years away, and Osborne’s recent decision to increase welfare payments by 5.2 per cent, in line with a freakish inflation blip, will have only strengthened the welfare trap).‘UK firms seem to be reluctant to hire younger workers and, where they do, show a preference for foreign staff. For example, over the last year, employment among UK-born workers fell by 208,000, while employment among foreign-born workers rose by 212,000. We advocate a lower minimum wage for people aged below 25 years, a further easing of regulations over firing people, and a requirement that all UK schoolchildren have to study at least two foreign languages to at least age 16 years (ie GCSE standard). The UK aims to be a major centre of global service industries, and such industries probably prefer people who can communicate easily to a range of global contacts.’

The British government has been pathing the road towards welfare dependency, and ought not to be surprised if so many young people walk down that road. The above graph shows a failure of British government policy, not of British youth. But this leads us to a fourth factor, which Saunders refers to above (and I’ve referred to before — you might call the ‘Pret A Manger factor’): a preference by employers for foreign-born workers. Again, this is not the fault of the employers but the state. If I was getting just 5 per cent of every pound I earned, I’m not sure I’d be serving sandwiches with a smile.

You can’t change a culture overnight. But you can change the tax system. All of this strengthens the case for an emergency tax cut for the low-paid in the next Budget. Raising tax thresholds to £10,000, as the Liberal Democrats propose, is the only idea being taken seriously inside the Treasury. It sounds strange to say it, but for those wanting to see taxes cut for the low-paid Danny Alexander is our best bet.

Comments