There are lots of reasons why non-scientists should be forced to study mathematics, but it’s hard to see why mathematicians should bother with literature. Literature is part of the entertainment industry: emotional manipulation, crippled by cheap assertions and hollow arguments. Maths is intellectual. Maths has rigorous standards. Literature hides guff under its pretty phrases.

Hart discusses the statistical challenges for the Oulipo group and their refusal to use the letter ‘e’ in thir clvr novls

Sarah Hart, a professor of mathematics, wants us to see literature and mathematics as the ancients did – mutually supportive, central elements of a rounded education. Once Upon a Prime is an eager, straight-forward book. There is maths but, unless you’re embarrassingly innumerate, it’s not hard to grasp; there is Tiggerish enthusiasm. Like an eager parent trying to cajole a sullen child, she occasionally over-peppers her prose with exclamation marks and a little too much joshing modesty, but that’s not her fault, it’s ours. We non-mathematicians are sullen about maths. That a theoretician of the calibre of Hart has any desire at all to stoop down and include us in her glorious subject is cause for celebration. She is at her best when talking about literary structure, poetical form and combinatorics.

In chapter 3, about the literary group Oulipo, she discusses the statistical challenges for Frenchmen who refuse to use the letter ‘e’ in thir clvr novls. Oulipo’s aim is to explore fresh ways to mould literature, using mathematics. Raymond Queneau, one of the group’s founders, published 100 trillion poems in a ten-page book: he wrote ten different sonnets, then invited readers to pick their first line from any one of them, combine it with a second line, again from any one of the ten on offer, follow it by a third, also plucked from the sample of ten – giving 1014 possible combinations in all. B.S. Johnson, not to be outdone, puffed up his chest and nine years later published The Unfortunates, a novel with 25 chapters that could be read in any order, giving a total of – put this in your Gauloise and smoke it – 15.5 septillion versions.

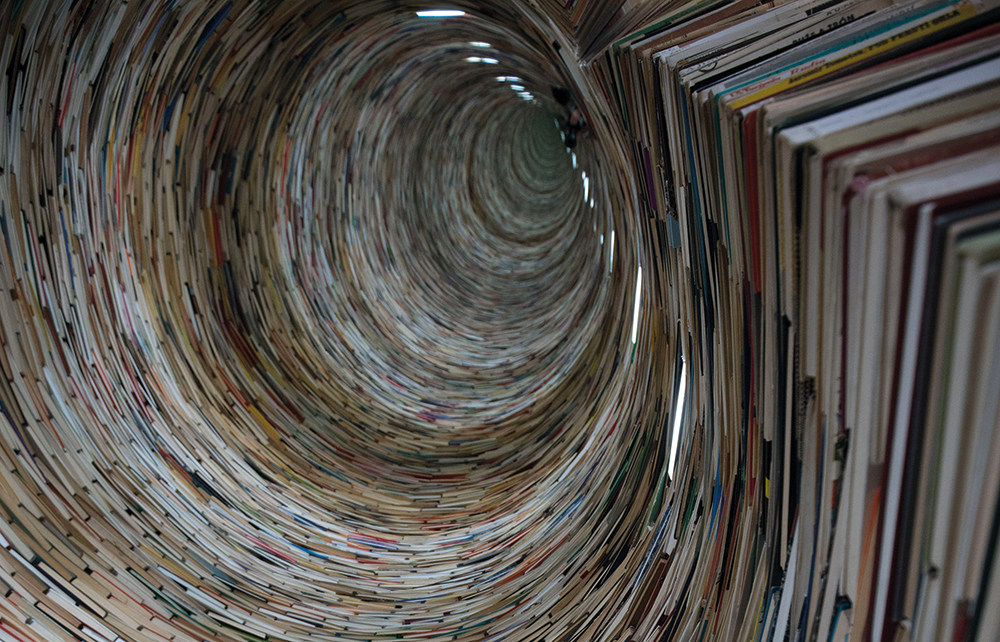

Jorge Luis Borges was much more interesting. In The Library of Babel he describes a library that contains all possible books. Every book that has been written, will ever be written, will never be written, can be imagined, and has never been imagined; as long as it could be a book, it is in the library. ‘Only the impossible is excluded. For example, no book can be a ladder.’ Once Upon a Prime is in it, but so are all the versions of the book that contain embarrassing errors or nothing but swear words. Somewhere, a finite distance from where you are standing now, is a volume that will describe each moment of the rest of your life. It is a large building, but not an infinite one.

Borges also reveals a few architectural details about the building. It is made up of identical hexagonal galleries with gargantuan air shafts running between, and separated by a narrow corridor, in which there are tiny closets where the librarians can sleep. From any of the galleries, one can see, stretching into the distance, millions of floors above and below. Every gallery holds 640 books that are 410 pages long, have 40 lines on a page, 80 characters to a line, written in an unspecified language, with 22 letters and three extras: a comma, a space and a full stop. Borges’s detail peters out at this point – he has a story to write – but Hart charges on with glee: 410 pages x 40 lines x 80 characters per line means 1,312,000 characters per book… 25 characters in total (the alphabet plus those three extra) equals 251,312,000 volumes… multiply by, say, another 2540 to account for the text on the spine.

Suddenly, in the full flight of this nerdish fancy, Hart brings a hint of mathematical magic. These numbers mean that the writing on the book spines must include the character ö. Sarah Hart doesn’t share her initials with Sherlock Holmes for nothing.

I sputtered in my coffee, Dr Watson-like.

Hart explains her reasoning with amused patience. It’s an elementary mathematical insight. 251,312,040 is an idiotically large number. The number of atoms in the universe is only 1080. So, either the hexagonal galleries are billions of times smaller than an atom or the library exists in another universe.

How does that help? I guffaw. Do you mean in other universes there will be, perforce, the letter ö?

Not at all. 251,312,040 tells us that one of Borges’s galleries is not full.

My dear Hart, I admire you greatly, I believe in the importance of your work; but how can you possibly…

Because 251,312,040 is an odd number.

I had a brief image, as I wiped up my coffee, of Hart flashing out, trillions of light years, to the edge of a parallel universe and checking that last digit on the wiggling end of 251,312,040 was not 2, 4, 6, 8 or 0. But she had deduced this result more simply. Any odd number multiplied by itself is odd; 25 doesn’t give up being odd just because you keep harassing the poor thing 1,312,000 times. Yet Borges has already told us that every gallery in the library contains 640 books, and 640 is an even number, so it can’t go into 251,312,040. One gallery in the library is therefore only partially full: the library is imperfect. And this means… but I won’t give away all Hart’s sleuthing insights.

Five pages later, she has deduced the solution, filled up all the rooms nicely, and worked out that the entire library must be built as a torus. Hart is well named as well as well initialled: she is kind.

From the galleries of Borges’s library one can see, stretching into the distance, millions of floors above and below

For structure, clever writers go to arithmetic. Georges Perec’s magnificent Life: A User’s Manual is set in a hotel that is ten floors high, with ten rooms on each floor. He worked out the contents of each room with the help of two overlapping 10×10 Latin squares – rather like entwined Sudoku puzzles – that he cross-referenced to a pile of lists he’d made beforehand. The result is exquisite: rich, surprising, otherworldly, yet intimate. The length and form of Eleanor Catton’s superb, ever-tightening Booker Prize-winning novel The Luminaries is also based on mathematics. The chapter lengths follow a geometrical progression with the sum 2L(1 – 1/4096), where L is the length of the first chapter and 4096 the value of the gold that has been stolen at the start of the book. Amor Towles’s international bestseller A Gentleman in Moscow also uses geometric progression: leap the story forward by jumps that double in length of time, from one day to 16 years until the middle of the book, then flip, invert and halve in time until the final day, 32 years later. It’s not so much the particular pattern that is valuable to these writers as the sense of constraint; the protection maths offers against uncontrolled imagination.

At the end of her best chapter, on the mathematics of poetry, Hart quotes Karl Weierstrass: ‘A mathematician who is not somewhat of a poet will never be a perfect mathematician.’ It’s one of those tingly, kaftan-wearing sentences that I never quite understand. Does the fact that today’s computers can do original mathematics – discover in a few minutes new and remarkable proofs and unexpected connections that would have taken humans perhaps another 1,000 years – mean they are poets? The only really good mathematician I’ve ever known plucked his wizardry out of thin air. His insights were driven by a sense of balance and beauty, not by proof. Poetry came before proof. But poetry also misled him. It was as untrustworthy in mathematics as it is in emotional life.

Hart also quotes Ezra Pound’s reversing of Weierstrass’s aperçu: ‘Poetry is a sort of inspired mathematics. It gives us equations… for the human emotions.’ But this doesn’t wash either. There’s a reason why after, for example, watching someone they love die, people often can’t read novels or poetry or listen to music: art feels cheap; a skin over chaos, nothing more. Maths – its lack of self-indulgence, its firm but fair standards, its clean, straightforward acceptance of fact – does a better job of consolation. ‘I take walks, play on the piano, read Voltaire, talk to my friends,’ wrote George Eliot after a particularly trying year, ‘and just take a dose of mathematics every day.’

By the end of Once Upon a PrimeI still didn’t understand why mathematicians should bother with literature, but I felt doubly grateful that literature has had the sense to steal from mathematics. Put these two sundered friends together again, as they used to be in ancient times, and you reach the pinnacles of elegance. How much more would your children love you if you could only write out their homework like the 12th-century poet and mathematician Bhaskara:

Out of a swarm of bees, one fifth part settled on

a blossom of Kadamba,

And one third on a flower of Silindhri;

Three times the difference of those numbers

flew to the bloom of a Kutaja.

One bee, which remained, hovered and flew

about in the air,

One bee, which remained, hovered and flew

about in the air,

Allured at the same moment by the pleasing

fragrance of jasmine and pandanus.

Tell me, charming woman, the number of bees.

Comments