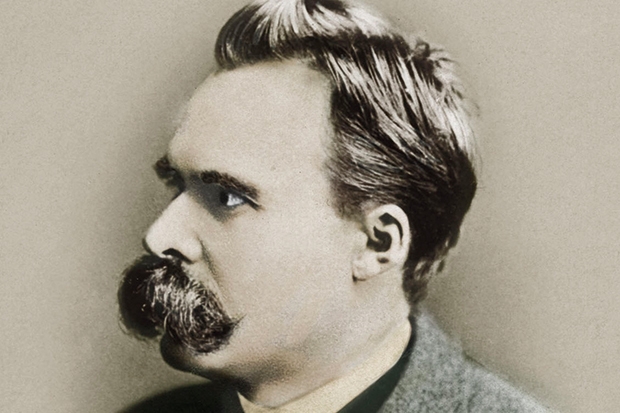

Had you been down at Naumburg barracks early in March 1867, you might have seen a figure take a running jump at a horse and thud down front first on the pommel with a yelp. This was Friedrich Nietzsche, midway through his 23rd year and, thanks to a sickly childhood, no stranger to hospitals. Nietzsche lost part of his sternum, leaving him not so much pigeon-chested as angle-grinded. Once recovered, he celebrated by having his picture taken in full uniform, sabre at the ready, glaring at the ‘miserable photographer’ like a warrior set for battle.

Daniel Blue regards the photo as ‘unflattering’ — though it’s nowhere near as unflattering as the picture Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche painted of her brother after his death in 1900. Rabidly anti-Semitic (in later years she would support Hitler), Elisabeth rewrote and restructured Nietzsche’s unpublished manuscripts so as to make this anti-racist internationalist read like a Nazi before the fact. Blue doesn’t mention that, but he does cite some of Elisabeth’s other misrepresentations and believes that most of Nietzsche’s biographers have erred through their unthinking acceptance of Elisabeth’s ‘statements and stories as uncontroversial facts’. Hence The Making of Friedrich Nietzsche, a volume which ‘aspires to be the biography that Nietzsche himself might have composed if he had possessed the inclination and the time’.

In fact, Nietzsche spent a good deal of his early years composing just such books. He completed his first memoir when he was just 13, and wrote another five over the next decade. They weren’t written to record his academic achievements (negligible, at least until his mid-teens), much less his prowess on field or track (non-existent), but, rather, according to Blue, as a ‘mirror’ in which, abstracted from history and environment, his ‘latent self’ would come into focus. ‘Autobiography’ was what Nietzsche wrote ‘in order to see who he was’.

On the evidence adduced here, what he was was a mummy’s boy. As late as her son’s undergraduate days, Franziska Nietzsche was still doing her son’s laundry. And whenever a more metaphysical storm broke, mum was always Nietzsche’s first port of call. Even when he was called away from his studies for military service, he was granted a dispensation that posted him in his hometown — and allowed him not only to live at home with Mum, but to lunch and dine with her every day of the week. Blue, who seems to have read everything ever published on Nietzsche (and translated much new material hitherto available only in the German), doesn’t mention Joachim Köhler’s Zarathustra’s Secret: The Interior Life of Friedrich Nietzsche. Nonetheless, he does an awful lot to endorse Köhler’s suggestion that Nietzsche was a repressed homosexual.

But does Blue offer as radically new a portrait of Nietzsche as he claims? On the whole, I’m afraid, no. In essence, what this book does is translate into biographical terms the more analytical findings of Walter Kaufmann’s still groundbreaking study Nietzsche: Philosopher, Psychologist, Antichrist. Prior to the publication of that book in 1950, it was a critical commonplace that Nietzsche was a crazed Teutonic supremacist whose poetic ranting was of no philosophical worth. Kaufmann went back to the original texts to show how, far from being a proto-dictator, Nietzsche (who once called himself the ‘last anti-political German’) was in fact a proto-existentialist — a rationalist moralist who believed that the only thing worth conquering was the self.

Subsequently, of course, Nietzsche has gone on to conquer legions of readers. Who doesn’t love a writer who stops being apophthegmatic only in order to be aphoristic? Nietzsche isn’t just the greatest stylist in the history of philosophy. He’s one of the greatest stylists in the history of the written word. As with Shakespeare, reading Nietzsche is like reading a dictionary of quotations: practically every line seems both familiar and startling.

Which means that the big drawback of Blue’s impressively researched book is its prose. Though he calls himself an ‘independent scholar’, Blue writes the purest acadamese — a stodgy slurry in which nothing goes without saying and, as if in homage to Nietzsche’s notion of eternal recurrence, many things are said more than once. ‘Without music,’ remarked Nietzsche, ‘life would be a mistake.’ Daniel Blue’s book is without music. Even though it sets his record straight, Nietzsche wouldn’t have approved.

Comments