For an orchestra to lose one anniversary concert may be regarded as unfortunate. To lose two? Welcome to 2020. The City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra gave its first ever concert on 5 September 1920. But that was only a warm-up, a sort of soft opening if you like. The big public fanfare came two months later, on 10 November 1920, when the all new ensemble descended on Birmingham Town Hall for an inaugural gala conducted by Sir Edward Elgar. The plan in Birmingham this year was to recreate both events, in lavish style.

Well, life comes at you fast, doesn’t it? Go online, came the cry from 1,000 armchairs, but streaming costs money that most arts organisations don’t have right now, and a lot of space is required to house a full symphony orchestra without deafening the musicians — even without social distancing. The CBSO streamed its September centenary concert from a warehouse in Longbridge while Birmingham’s Symphony Hall stood empty up the road, a casualty of the lockdown. You can’t reactivate a building as complex as a modern concert hall by walking in and flicking a switch. When the cash eventually came through and Symphony Hall reopened, the CBSO announced a scaled-down centenary concert — complete with audience — for 10 November. They’d got as far as drafting the marketing copy when, wham! Lockdown 2.0. No audience. Game over, again.

The Covid-era format is starting to feel routine, even – god help us – reassuring

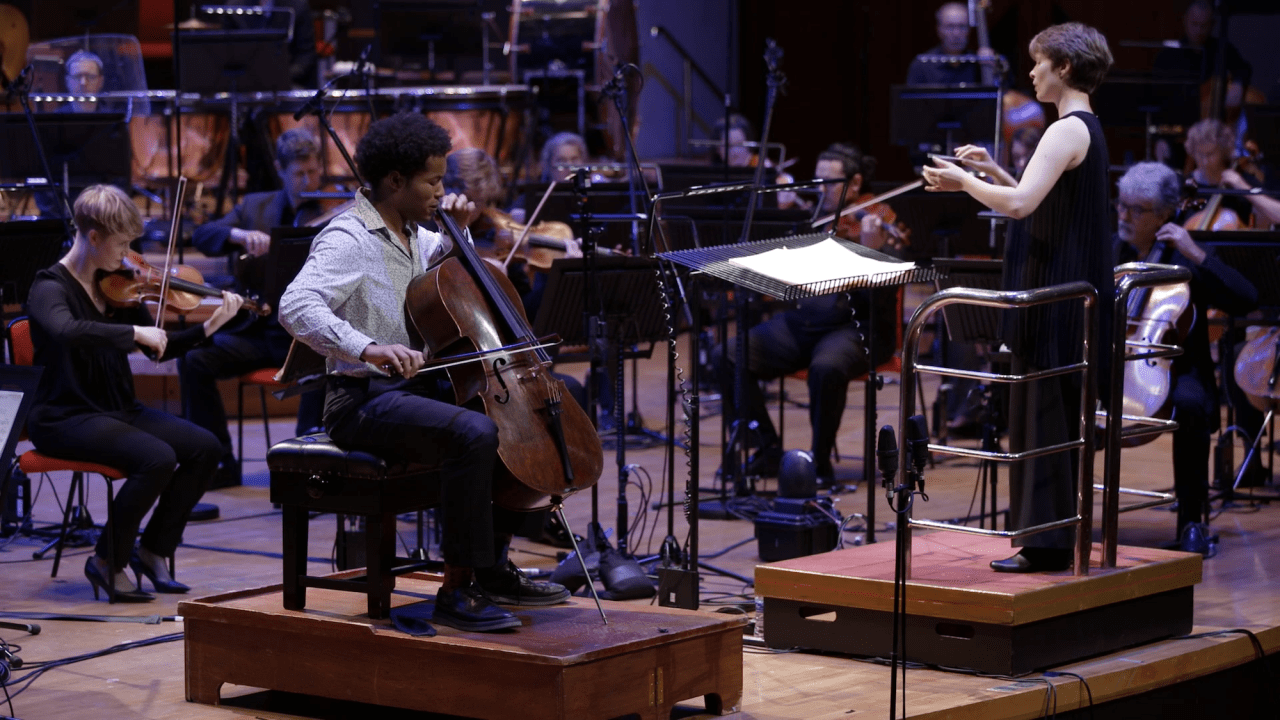

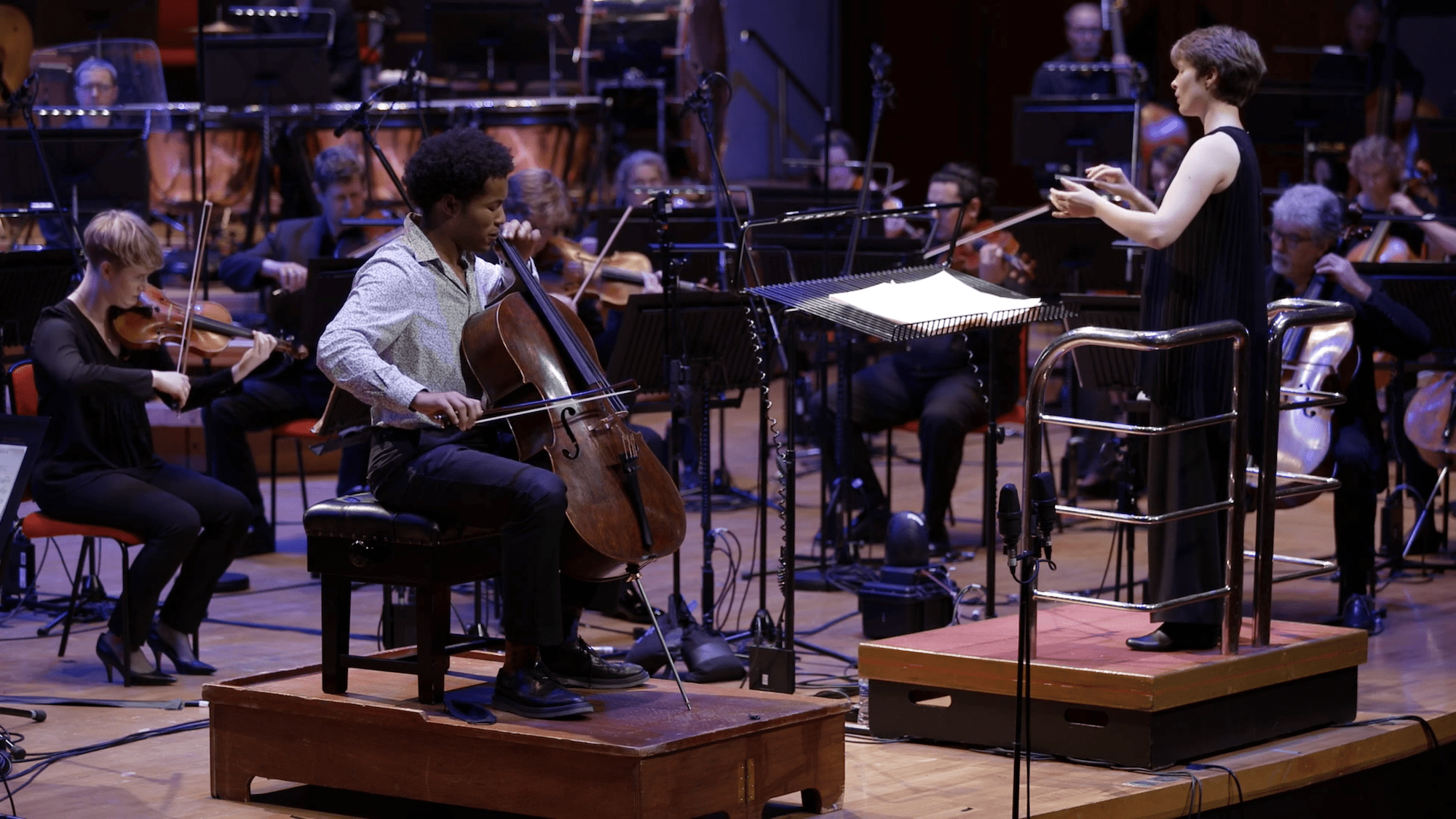

The orchestra played the concert anyway, and the results are now online. What shocked me most was just how unfazed I’ve become, after barely six months, by the utter weirdness of the Covid-era format. The empty seats, the yawning gaps between musicians, the absence of applause: it’s starting to feel routine, even — god help us — reassuring. Mirga Grazinyte-Tyla conducts, and contributes a short spoken introduction in the enthusiastic, animated manner familiar to Birmingham audiences, and which so infuriates classical music’s cloth-eared, faintly creepy community of message-board misogynists. The orchestra’s Argentinian principal cellist Eduardo Vassallo joshes cello soloist Sheku Kanneh-Mason about the football results. Prince Edward (the orchestra’s patron) talks about Elgar’s Cello Concerto. ‘Elgar’s music is also closely connected with my own family,’ he deadpans.

As for the music (the Elgar, plus Beethoven’s third Leonore overture and two of Sibelius’s Lemminkainen Legends): well, having had some small involvement in the CBSO’s ill-fated centenary plans, I was predisposed to enjoy it, though I don’t think it’s unduly partial to say that Kanneh-Mason’s interpretation of the Cello Concerto has evolved since he recorded this work in 2019. There’s a focused, increasingly refined quality to his sound. His phrasing is eloquent in its restraint; passions flare up and are swiftly corralled back in line. The result is somehow more affecting — more vulnerable — than if he’d simply opened the emotional sluices. Elgar had a word for it: nobilmente.

Of course, Kanneh-Mason is still only 21; he’s at the start of a long road. Instinct suggests that his journey will be worth following, though you might not guess that from his recordings alone. And that’s the basic problem with online concerts too, or at least, the aesthetic problem. (The finances are another matter. Classical musicians are cagey about figures but it’s rumoured that even the Berlin Philharmonic’s Digital Concert Hall — a premium online product with an unrivalled global brand — has yet to break even.)

It’s not as though orchestras have much choice — they have to be seen to be doing something — but digital concerts normalise yet another form of canned and processed music, when all that should really matter is live performance. (Yes, a funny complaint to make after 130 years of recorded sound, but this is The Spectator. Tilting at windmills is part of the remit.) Sergiu Celibidache reportedly said that listening to recorded music is like making love to a photograph. What he’d have thought about listeners sitting alone in darkness, hunched over downloaded images on flickering screens, is probably best left to the imagination.

But we are where we are; and I derived real, if solitary, pleasure from the CBSO’s latest online performance, in which Grazinyte-Tyla conducts Vaughan Williams’s Tallis Fantasia and John Ireland’s Downland Suite. The Fantasia works like a dream; you almost feel the shimmer in the air as Grazinyte-Tyla pulls long, singing lines from Vaughan Williams’s lush textures, and the second orchestra floats translucent answering chords from the vicinity of the choirstalls. The Ireland is more of a surprise — a brisk, sometimes wistful showpiece for brass band by one of Britain’s more reliably understated composers. Grazinyte-Tyla conducts a version for symphonic brass that transforms Ireland’s monochrome linocuts into Eric Ravilious watercolours, and she does it with a smile. A Lithuanian pupil of Mariss Jansons champions obscure British brass band music? Even in a year as bizarre as 2020, I did not see that coming.

Comments