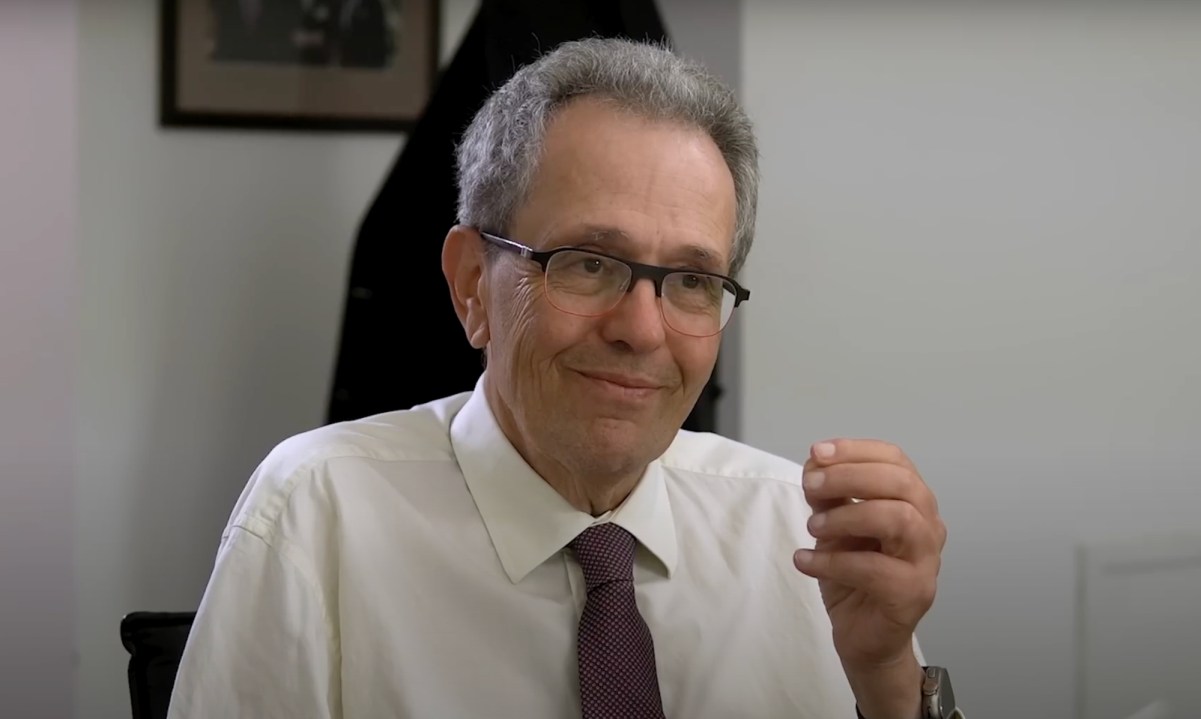

The long-time Spectator contributor Jonathan Miller has died. James Tidmarsh remembers him here:

Jonathan Miller liked to say that Emmanuel Macron was the gift that never stops giving. ‘The Spectator can’t get enough of him,’ he told me. ‘Macron serves up fresh spin, scandals and missteps, an endless supply of stories for any journalist willing to look behind the official line.’ When we first crossed paths on X, we’d swap messages about ministers, café gossip, and the small absurdities that make French politics so irresistible. Jonathan was usually in his village in the Languedoc sunshine. He loved it there and seemed content when describing the rhythm of village life.

Jonathan Miller made trouble where it mattered and never stopped

When he wasn’t working or with his family, he was walking the dogs, sitting in a café or talking to his French neighbours. He told me the magic of France was that it gave him endless stories, but also peace. He insisted French politics was a goldmine, that the stories wrote themselves if you looked behind the official line.

Jonathan was a newsman through and through, who spent decades in the US and Canada – Detroit, Cincinnati, Dayton, Washington. He learnt his trade on the police beat, chasing crooked cops, city hall scandals and covering national and international stories. In his memoir, soon to be published, he recalls the days when a reporter could cross the yellow police tape with a press card and get the story before the competition. He and his colleagues kept police scanners on their desks so they could race to murder scenes before anyone else. He wrote about the thrill of learning to pick out the small details that made a story stand out. That sense of beating the pack, he said, kept him hooked on local journalism long before the foreign assignments came. He remembered stealing rubbish from administration buildings in Cincinnati to piece together city hall scandals and chasing down police corruption stories that others were too timid to touch. Andrew Neil once called him a ‘bare-knuckle journalist’. He believed in the old Chicago city news bureau rule: ‘If your mother says she loves you, check it out.’

One of my favourite lines from his memoir goes back even further, when he was at school in Hampshire before his family moved to Canada for his father’s job: ‘When I was at Bedales School, my history teacher Ruth Whiting, in her signature green ink, scrawled on the bottom of one of my essays the single word, “journalese”. She meant it as an insult. I took it as career advice. I didn’t learn much else there. Pace Mark Twain, I never let schooling interfere with my education.’ This is how Jonathan saw the trade: something you learn by doing, with your eyes wide open.

In Kosovo, he found himself less interested in the press pack chase for war footage than in getting a single family out of the country to safety. A reminder, he said, that not every journalist had to be as cold-blooded as the job sometimes demanded. His memoir is full of these scraps: the dark corners of American city politics, the Detroit murders, the Dayton city hall intrigue, the stolen documents, the small acts of compassion that don’t make headlines.

Jonathan was the one who told me to try my hand at The Spectator. He encouraged me to be braver, sharper, and to lose my caution. ‘You’re too much the lawyer’, he’d say. ‘Don’t sit on the fence. You have an opinion, write it. And for heaven’s sake, don’t be afraid to offend.’ He enjoyed coaching me through a lead paragraph, needling me when I hedged. He’d call after a piece went up, to push me further. He went out of his way to be generous with his time, ringing just to say what he thought, the best sort of advice any writer can get.

This past year, he spent much of his time writing his memoir. It is a proper, unapologetic look at the journalism trade, the spike on the desk, the moments when you need to write unflinchingly, even when editors urge caution. Jonathan’s book, Shock of the News: Confessions of a Troublemaker, comes out this August with Gibson Square Books. It’s an ode to the dead-tree press and for the troublemakers who made it matter, told by someone who never forgot what the job was for.

Jonathan Miller made trouble where it mattered and never stopped. He knew that good stories ruffle feathers, that good journalists never get too comfortable, that you should never trust the official version without first checking the bins behind the building. I’ll miss him. And so will journalism, the kind that still remembers what real trouble looks like.

Comments