Back in 2008, Boris Spassky paid a visit to Bobby Fischer’s grave in Iceland. ‘Do you think the spot next to him is available?’ he mused. Last week, Spassky died too, at the age of 88. The two world champions were rivals, but also the unlikeliest of friends. Spassky was born in Leningrad in 1937, and won recognition at the age of ten by beating the Soviet champion Mikhail Botvinnik in a simultaneous exhibition. By the age of 18, he had earned the grandmaster title and qualified for the Candidates tournament in Amsterdam, 1956. Ten years later, he played a world championship match against Tigran Petrosian, but lost narrowly: 12.5-11.5. Spassky, who is often described as having a ‘universal’ style, qualified for another match with Petrosian in 1969. His versatility made him an even stronger challenger the second time around, and he won the match by 12.5-10.5, to become the tenth world chess champion.

Spassky’s challenger in 1972 was Fischer, when they contested the ‘Match of the Century’ in Reykjavik; a Soviet champion and an American challenger, at the height of the Cold War. Were it not for Spassky’s sportsmanship, that match might never have happened. The volatile Fischer failed to turn up for the opening ceremony, and Spassky resisted political pressure to claim victory by default. When the match finally began, Fischer lost the first game and forfeited the second after a dispute over the playing conditions, demanding to play without cameras and spectators present. Spassky acceded, evidently determined – to his credit – that the match must be decided over the chessboard. But that proved a turning point, and the negotiations undoubtedly took a psychological toll on Spassky. Fischer dominated the rest of the match and won by 12.5-8.5. Despite the tension, they remained on good terms, even playing an unofficial rematch in Yugoslavia in 1992, with Fischer competing in defiance of US sanctions.

In 1975, Spassky married for the third time, to Marina Shcherbachova, and they emigrated to France the next year. He became a French citizen, and later represented France in three Olympiads, though in the latter years of his life he returned to live in Moscow.

A beautiful win from Spassky’s youth, against a great player of the older generation.

Boris Spassky-David Bronstein

USSR Championship, Leningrad, 1960

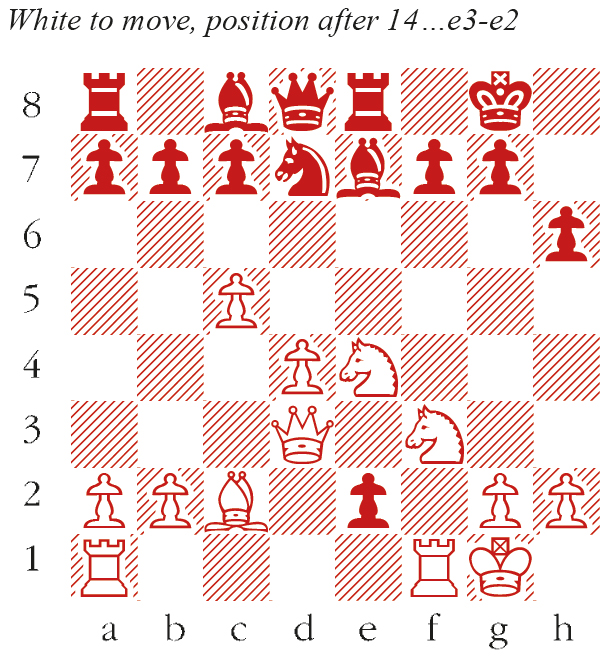

1 e4 e5 2 f4 Spassky played the King’s Gambit in dozens of games against world-class opposition. exf4 3 Nf3 d5 4 exd5 Bd6 Bronstein, another avid King’s gambiteer, would not wish to lag in development after 4…Qxd5 5 Nc3. 5 Nc3 Ne7 6 d4 O-O 7 Bd3 Nd7 8 O-O h6 9 Ne4 Nxd5 10 c4 Ne3 11 Bxe3 fxe3 12 c5 Be7 12…Bf4 13 g3 Bg5 14 Nfxg5 hxg5 15 Qh5 yields a decisive attack. 13 Bc2 Re8 14 Qd3 e2 (see diagram) Aiming to divert the queen from the key b1-h7 diagonal. In fact, 15 Qxe2 was best, but Spassky had a fantastic idea, sacrificing his rook with check. 15 Nd6!? Nf8? One alternative was 15…exf1=Q+ 16 Rxf1 Nf6, which runs into 17 Nxf7! Now 17…Qd5 18 Nxh6+ is crushing, but the really beautiful point arises after 17….Kxf7 18 Ne5+ Kg8 19 Qh7+!! Nxh7 20 Bb3+ Kh8 21 Ng6 mate. A better defence was 15…Bxd6 16 Qh7+ Kf8 17 cxd6 exf1=Q+ 18 Rxf1 cxd6 19 Qh8+ Ke7 20 Re1+ Ne5 21 Qxg7, but the attack remains very dangerous. Fearing this, Bronstein chose something worse. 16 Nxf7! exf1=Q+ 17 Rxf1 Bf5 17…Kxf7 18 Ne5+ or 17…Qd5 18 Bb3 are no better. 18 Qxf5 Qd7 19 Qf4 Simple chess. The attack is overwhelming. Bf6 20 N3e5 Qe7 21 Bb3 Bxe5 22 Nxe5+ Kh7 23 Qe4+ Black resigns

Comments