Rwanda

It had been more than 30 years, yet I recognised the church and its surroundings instantly. Superimposed on the tidy green sward of today, I recalled the rags, shoes and corpses I saw here in May 1994. There are gaps in my memories of Rwanda. But the parts I do recall are explosively vivid, as if branded on my retina, like those people outside the church. They’d lost heads and limbs and every-body was dead, but the scene was alive. I could see and hear their last moments. A woman lay in my path, on her back with her gingham skirt hitched up around her thighs. Not much flesh left on her skeleton, her hair sloughing off, her face and frame frozen at the end of her rape, when her attacker shot her in the heart.

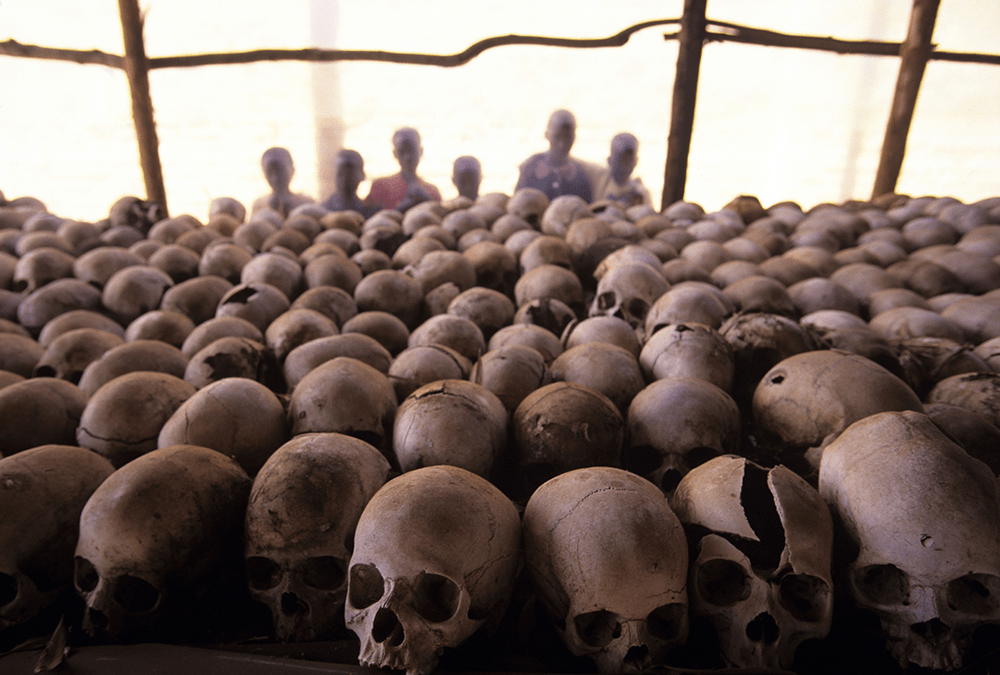

I knew a TV man who filmed violence for years without a break until one day he entirely lost the use of his arms

The memory of it remains as if encased in amber, that brief glance down at the woman on the grass, before I went on. As we entered the church on that first day, the black floor buckled and disintegrated as millions of flies took to the air above a tangle of rags and limbs and bags of guts. I gave up counting the bodies. Today, the church interior is full of ivoried skulls tidily arranged on shelves. Back outside, where we had sat down on the grass to watch clouds of butterflies, white with orange-tipped wings, flexing on the edges of mud puddles around the corpses – today there is a wall engraved with all the names of the dead who could be identified. I felt great admiration for the Rwandans who had built this memorial, that for once in Africa everybody who died here had been commemorated as people rather than lost in that pile of nameless death.

‘Never, in peace or war, commit your virtue or your happiness to the future,’ wrote C.S. Lewis – and to that, I’d add, never make your happiness, or unhappiness, depend on the past. Inevitably the correspondents who covered central Africa’s bloodletting in the 1990s were wounded by memory. I knew a TV man who filmed violence for years without a break until one day he entirely lost the use of his arms, which became paralysed, as if his brain and body were in rebellion, so that he could not raise a camera to his shoulder to film another horror. Yet from what I recall, I frankly enjoyed my work in places like Rwanda, Somalia and Ethiopia. Observing conflicts, revolutions and catastrophes in the exterior world worked to neutralise the noisy discord inside me, and in the work I did as a reporter I had a sense of purpose. As for any damage that might have occurred, like having a pebble in your boot on a fast march which you have no time to halt and remove, you adjust your gait so that you can try to avoid developing a blister. As you march on, even if your gait is out of kilter, you can begin to forget that the pebble is even there. No doubt the pebble took its toll over time, and I do have my regrets. ‘You are just an arsehole,’ somebody close said to me recently – and there might be no treatment for being just an arsehole.

On a hill in downtown Kigali, capital of Rwanda, there is a series of compounds that surround the redbrick Catholic church of Sainte Famille. During the battles over Kigali in 1994, thousands of Tutsis took refuge in the Sainte Famille complex and when we could get through the militia roadblocks, we would visit to report on how the people were doing there. At the entrance there was always a group of armed young men, swigging from large bottles of beer. Inside, the concentration camp conditions were oppressive, and ruling over the site was the bizarre figure of Father Wenceslas, a priest who wore a dog collar and a flak jacket, while packing a pistol. He claimed to be protecting the civilians in the Sainte Famille, but after dark each night the militias entered the complex through holes in the walls and seized people to slip away with and slaughter.

On my more recent visit to Kigali, we went to the Sainte Famille to hear Mass and the church was packed, clearly with people who had been on both sides in the conflict three decades ago. In the street outside, the scent of flowering trees dropped in the sunshine and the air was heavy with the sound of bees. After what the worshippers taking Mass had gone through with their families in 1994, they had done a fine job of rebuilding their lives and moving on. Who were any of us outsiders who saw what happened to say that we could not move on too? According to C.S. Lewis: ‘The present is the only time in which any duty can be done or any grace received.’

Comments