A few years ago, a French reader congratulated me on my marvellous biography of Napoleon. Yes, I agreed, it’s a terrific read — an absolute blinder. But I had to be frank and reveal that, alas, I wasn’t Frank.

I confess to being a little envious of my approximate namesake, Frank McLynn. A hugely successful popular historian who has the freedom to write on just about any subject he damn well pleases: Marcus Aurelius, the Burma campaign, the battle of Hastings, Jung, the Wild West. He even has a sideline on Hollywood greats. With some two dozen books to his name, he has clearly grasped the baton from Christopher Hibbert. Such eclecticism should come at a price — and occasionally it does, if only a nominal one — but he keeps his many readers happy, and will do so again with his new book.

The Road Not Taken purports to ask how it is that Britain has avoided, as McLynn sees it, the type of full-blooded, ‘true’ revolution experienced in so many other countries (France, Russia, China, Mexico and Cuba, for example). However, his focus instead rests on the established methodology of cause, course and consequence of seven ‘clear revolutionary situations’.

It is debatable whether all McLynn’s choices were indeed such near misses; of the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, the Jack Cade rebellion of 1450, the Pilgrimage of Grace of 1536, the English Civil Wars of the 1640s, the Jacobite Rising of 1745-6, the Chartist Movement of 1838 and the General Strike of 1926, how many really nearly threatened permanent change of the whole regime? And surely the Magna Carta rebellion of 1215 should be included, with its profound implications for the restriction of kingship under conciliar probation? Even more curiously for an historian who specialises in the 18th century, McLynn consciously chooses to exclude the Glorious Revolution of 1688 on the grounds that it is merely a ‘rank zero’ or ‘alleged’ revolution, being simply a transfer of power ‘within a given elite’. I am all for bashing the Whigs but this goes too far: it was not the bloodless transformation of myth and it had a profound effect on many ordinary folk, too. (It also undermines the book’s assertion that Britain has not been successfully invaded since 1066.) McLynn’s interest is decidedly in revolution from below. Ultimately his choice of revolutionary moments is, as ever I suspect, based on his wish to write about, yes, whatever he damn well pleases.

The book does not require one, big corset binding hook to hold its expansive 600 page girth together, for it succeeds admirably as a fascinating and always enjoyable narrative and analysis of insurgency. Besides, McLynn discusses other unifying themes common throughout the period. Chief of these are economics and war, often going hand in hand. It was no coincidence that the Peasants’ Revolt and Jack Cade’s rebellion erupted against a background of setbacks and, in the latter case, outright disasters during the Hundred Years War; the financial cost of campaigning — increased by the curtailment of lucrative booty from France — was laid on the King’s subjects through taxation, exacerbating existing deleterious conditions that pushed avoidance to outright rebellion. No wonder, in 1381 when the peasants stormed London, they went on a rampage, beheading all those associated with the recently imposed and much hated Poll Tax. Their main target was Simon Sudbury, worldly Archbishop of Canterbury and, more to the point, Chancellor of the Exchequer, a recent promotion that ended rather than enhanced his career:

He did not die well; first he begged, pleaded and wept for his life, then, when the axe descended, it took no less than eight strokes to finish him off.

At least he was spared the post-decapitation fate, not recounted here, of the Chancellor of Cambridge University and the Prior of Bury St Edmunds: the peasants spiked their heads on lances and gave them lead roles in a macabre puppet show, in which the disembodied performers chatted and kissed each other.

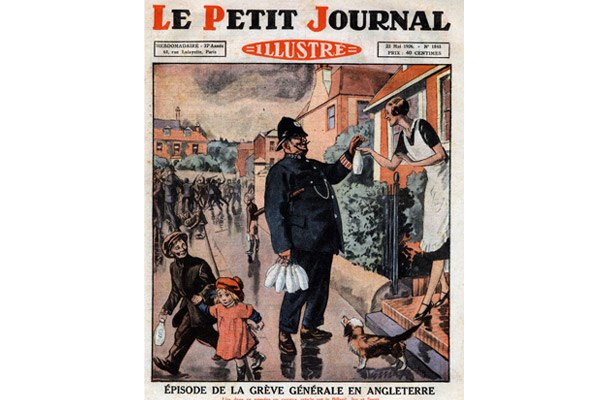

In the modern era, potential revolutionaries were more restrained but no less concerned for their livelihoods. The disparate movement of Chartists demanded parliamentary and electoral change, but this was primarily a means to improve economic conditions; the General Strikers of 1926 might not have feared starvation like their protesting predecessors, but theirs was the perpetual concern to provide dignity and security for their families. Memories of the French Revolutionary wars, and the economic dislocations of the pyrrhic first world war victory, added further volatile ingredients to the bubbling cauldron.

McLynn rightly gives religious reasons as the overriding motivation for the rebels taking up arms in the Pilgrimage of Grace against Protestant reform and the first round of the dissolution of the monasteries, but he perhaps understates the economic factors here, not least the worrying loss of monasteries as providers of jobs and, crucially, charitable and welfare services. The latter is raised in the Pilgrims’ Ballad, not used by McLynn:

How the pore shall mys / No tong can tell / For ther they hadde / Boith ale and breyde / At tyme of nede / And succer grete / In alle distresse.

A major theme of McLynn’s, and an enjoyable one, is exposing ‘the disastrously poor calibre of English leadership’ and ‘the obscene complacency of elites in history when faced by grotesque inequality’. Thus Stanley Baldwin was a ‘cunning’, ‘two-faced’ ‘prima donna’ suffering from ‘paranoia’. The ‘incompetent’, ‘pathetic’ Charles I was ‘one of those people who displaced or rationalised his own inadequacy by systematic duplicity’. I thought that I was well placed in the queue at the stocks to hurl rotten veg and dead cats at Henry VIII, but I yield to McLynn barging through with a flamethrower: ‘The most bloodthirsty and vengeful sovereign imaginable’, suffering from ‘hypertrophied egotism’, an ‘English Nero’, ‘the most horrendous of psychopaths’ (a term used at least four times) and ‘on some indices … the most despicable being who ever lived’. I knew he was a bad ’un, but gosh.

Do not, however, be fooled by this seemingly intemperate language; time and again McLynn’s judgment and analysis is informed and perceptive, all the while guided by his sound historical instinct, as in his unromantic assessment of the futility of insurrection citing Simón Bolívar’s experienced words: ‘He who makes a revolution ploughs the sea.’

For a postulation of Britain’s non-revolutionary Sonderweg (if that is what it was) to be fully convincing, there needs to be more developed comparisons made with foreign revolutions. Thus, while Rosa Luxemburg’s left wing ideas are discussed at length (leaving Karl Liebknecht in the shadow), the 1919 Spartacist uprising in Germany barely merits a mention. Ranging as widely as he does, McLynn is bound to miss nuances and connections, but these are nominal costs readily incurred for the satisfaction of reading yet another great book from an historian who writes with style and wisdom.

Comments