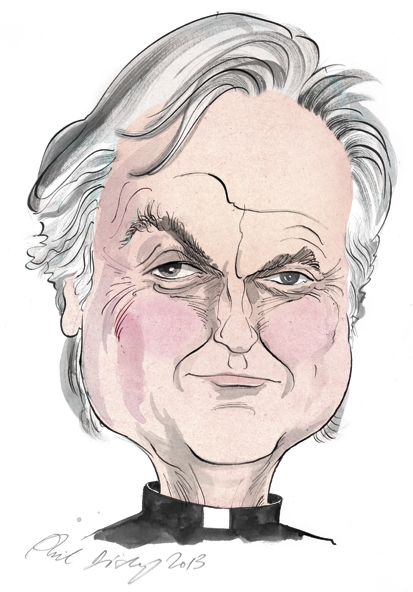

‘You owe me an apology,’ Richard Dawkins informs me. It is a bright Oxford morning and we are sitting in his home. His wife has just made me coffee and I have met their new puppies. I am here to discuss a new book of his, but he is smarting from a disobliging reference to him in a recent one of mine. That, and an earlier encounter I wrote about here, have clearly rankled. I try a very limited apology. But it does strike me that Dawkins is more easily bruised than one might have imagined. I wonder if it has anything to do with the deluge of criticism he attracts, provokes and possibly unwisely takes notice of on social media. ‘Do you feel beleaguered?’ I ask. ‘Do you?’ he fires straight back.

The sensitivity comes across in An Appetite for Wonder: the Making of a Scientist, the first of a projected two-volume autobiography. In this surprisingly charming memoir, Dawkins seems especially keen to pre-empt any critics who will attack him for his fortunate background and privileged education — Oundle School and Oxford. ‘Have you met the phrase “check your privilege”?’ he asks.

It is not the only sign of bruising. Throughout the memoir Dawkins makes a special effort to appear, well — how else can one put it — human. He is at pains to point out that he is much moved by poetry and music — particularly the poetry of the late 19th and early 20th century. He relates a poem that regularly moves him to tears, Belloc’s ‘To the Balliol Men still in Africa’, which finishes:

Balliol made me, Balliol fed me,

Whatever I had she gave me again:

And the best of Balliol loved and led me.

God be with you, Balliol men.

As his book makes clear, it was indeed Balliol — and Oxford as a whole — that ‘made’ Dawkins. Several generations of his family — nearly a dozen members in all — attended the college and it is a place for which he holds deep gratitude as well as affection.

What is Oxford to him? ‘Very much the tutorial system. I suspect even Cambridge doesn’t do what Oxford at least did in my time.’ His gratitude for the superb tutoring he received makes him caustic about what is out there in the profession today.

‘I think there is a sort of box-ticking mentality. Not just in the teaching profession. You hear about it in medicine and nursing. It’s a lawyer-driven insistence on meeting prescribed standards rather than just being a good doctor.’ He recently stopped teaching but says, ‘We were just beginning to have to fill in forms accounting for every hour of the day and I think it’s got worse since I retired.’ All of which leaves him more time for, among other things, his oldest adversary: God.

In his new book, Dawkins relates for the first time the full story of his schoolboy break-out as an atheist. In the chapel at Oundle, he helped lead a small insurgency of boys who refused to kneel. The school’s headmaster was in Oxford on the day that the young Dawkins took his university entrance exam and drove him back. During this lift, Dawkins writes, the headmaster ‘discreetly raised the subject of my rebellion against Christianity. It was a revelation,’ he says, ‘to talk to a decent, humane, intelligent Christian, embodying Anglicanism at its tolerant best.’

I ask him about this. ‘I’m kind of grateful to the Anglican tradition,’ he admits, ‘for its benign tolerance. I sort of suspect that many who profess Anglicanism probably don’t believe any of it at all in any case but vaguely enjoy, as I do… I suppose I’m a cultural Anglican and I see evensong in a country church through much the same eyes as I see a village cricket match on the village green. I have a certain love for it.’ Would he ever go into a church? ‘Well yes, maybe I would.’

But at this point he turns it back around again. I try to clarify my own views to him. ‘You would feel deprived if there weren’t any churches?’ he asks. ‘Yes,’ I respond. He mulls this before replying. ‘I would feel deprived in the same spirit of the English cricket match that I mentioned, that is close to my heart. Yes, I would feel a loss there. I would feel an aesthetic loss. I would miss church bells, that kind of thing.’

And what about the fear of losing the tradition? ‘Yes. I sort of understand that. I certainly would absolutely never do what some of my American colleagues do and object to religious symbols being used, putting crosses up in the public square and things like that, I don’t fret about that at all, I’m quite happy about that. But I think I share your Anglican nostalgia, especially when you look at the competition.’

Then how do we pass it on? How do we make sure that succeeding generations in our country — even if they do not believe — are not so stripped of their religious heritage that they are prey to ignorance and possibly much worse? Dawkins is surprisingly receptive to the worry — and hearteningly impervious to the curse of cultural equivalence.

‘I am thoroughly in favour of educating people in this country in the Bible,’ he says. ‘So you know where phrases like “through a glass darkly” come from.’ But wouldn’t students also have to learn the Koran and all other ‘religious’ books?

‘I don’t think you have to actually,’ he says. ‘Because if the justification for it is a literary one — since in this country we are on the whole not studying Arabic literature — it’s enough to know the King James Bible, like you have to know Shakespeare. European history you can’t begin to understand without knowing about the perennial hostility between Catholics and Protestants so I suppose for history we need to. But I don’t buy the feeling that because we have Christian faith schools we therefore have to have Buddhist and Muslim and Hindu faith schools as well.’

Nevertheless he is concerned that the nice bits of Christianity, let alone making a virtue of faith as a whole, can make the world ‘safe for the suicide bomber’. I put it to him that certain atheists are a bit too keen to lump in the old lady at evensong with the suicide bomber. Some time after 9/11 it became easy for people to say ‘all religion is bad’. Would he agree that we may only now be reaching the point at which we can say that some religion is slightly worse than others? ‘More than slightly,’ he answers.

But what would come next if everyone followed him? I put to him the argument Jonathan Sacks recently made in these pages: après Christianity le deluge.

‘I don’t think I buy that really. I live in a post-Christian world in Oxford, it is quite rare to meet somebody who is religious in academic life now and there is absolutely no tendency for rioting and mayhem and it is extremely civilised.’ (I resist the urge to make him check his privilege.) He is much influenced by a recent book by Steven Pinker which he says shows that we humans are in fact ‘just getting nicer’.

And what about his own followers? He does have some fervent admirers who seem able to worship him and turn on him with surprising ease.

‘Well I don’t know, I can’t help it if that’s true. I would absolutely hate anybody to take what I say as a sort of ex-cathedra pronouncement on how they should behave, I just want people to listen to the arguments and judge for themselves, that’s always been my goal.’

It has been — and he has probably been more successful at it than almost anyone else alive. As we say our goodbyes it guiltily occurs to me that Richard Dawkins is a man more sinned against than sinning.

Comments