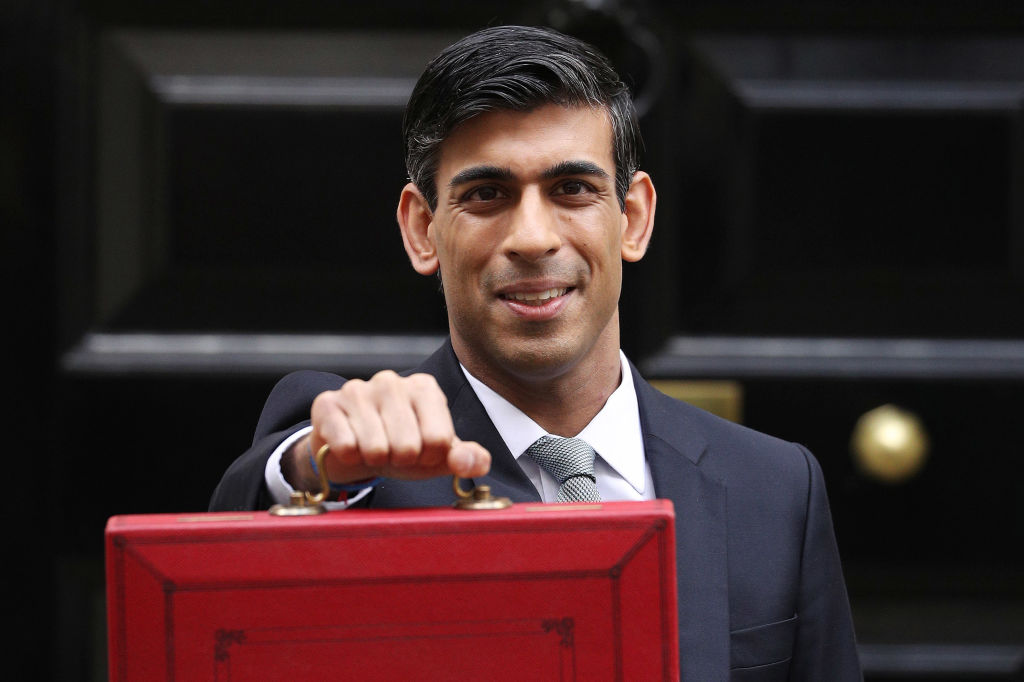

There are three dimensions to a UK budget: the political theatre, its underlying economics, and the measures themselves. My view is that the new Chancellor’s Budget speech was the most effective financial statement of any Chancellor since Nigel Lawson, for whom I worked as a Special Adviser. Rishi Sunak had a command of the economics, mastery over the detail to the measures and brought a political brio – not seen for 30 years or more – to the statement. The Budget offers an empirical, Conservative response to the circumstances of early 2020s. Understandably, however, some people are asking: what is Conservative about spending and borrowing hundreds of billions of pounds?

In terms of borrowing, put simply, the central question is not the scale of borrowing but the cost. The Budget papers show the cost of debt for the UK falling over the next five years, not rising. Why? This reflects low inflation, interest rates, and the international bond markets that trade UK government debt.

This budget has done – in macro-economic terms – what has been needed for some time.

We are living through a combination of very low levels of international price inflation and very low interest rates. These have transformed the costs and risks of using fiscal policy for governments in advanced economies. They have changed the trade-off between debt and tax in financing public spending. Even if rates were to rise, the UK has some of the longest maturity of debt among advanced economies, locking in the current level of interest rates.

From the perspective of bond markets, the UK is unusually well placed to borrow: it has one of the most efficient and best developed government bond markets in the world; a huge demand for its bonds from domestic insurance companies and pension funds, which has increased over the last 20 years; and significant demand from international banks and financial institutions. The role of sterling as a reserve currency has, if anything, increased since the construction of the eurozone, adding to that demand.

All of the above means investors are continually happy to accept very low interest on UK debt, which is good news for the government. And unlike the world before the 1980s, international bond markets are fully integrated – the borrowing by one government has little impact on the interest rate it pays.

Now let’s tackle the second pressing point. The UK is experiencing an adverse economic shock in the coronavirus, which is slowing domestic economic activity and creating a weakened international economy. An effective policy stimulus is needed to stabilise output. But as a reliable tool of economic management, monetary policy has run out of road when it comes to stimulating the economy due to zero-bound interest rates. Fiscal policy, such as targeted tax breaks or emergency loans, has to be used.

This budget has done – in macro-economic terms – what has been needed for some time. It has responded to an adverse economic shock with an active fiscal stimulus. The fiscal measures (such as the Business Interruption Loan Schemes and the breaks from business rates) have been co-ordinated with the central bank in the manner that was needed. In an economic environment where monetary policy and changes to interest rates have lost their potency as a source of stimulus, macro-economic policy has to mean fiscal policy co-ordinated with the monetary authorities; so that monetary conditions do not spoil the effects of a fiscal stimulus. The Sunak Budget is therefore an important watershed moment, offering an audacious example of the necessary future direction of travel.

For a Conservative, the question is whether borrowing is affordable in public expenditure terms. In the 1990s, Professor Robert Barro – who played a seminal role in formulating the economic theory that guided policymakers’ perception of the economic role of deficits – described a borrowing requirement of around 2 per cent of GDP as being a balanced budget in a modern economy. In the context of much lower interest rates today, the UK can afford much higher levels of borrowing. Professor Kenneth Rogoff – whose scholarship has warned governments about the dangers of borrowing – was very clear about borrowing and the contemporary British economy at Davos this year. As he put it, ‘The last thing on earth you should be worried about in the UK is the budget deficit.’

Comments