The alchemy wrought by a young man’s ability to gyrate and croon at the same time is notorious, turning shy mama’s boys from Presley to Rotten into love/hate machines. Something magical happens when someone – however unsightly – sings a song well, allowing him access to a quantity and quality of women undreamt of when he was just walking and talking like a normie. Two words: ‘Mick’ and ‘Hucknall’.

The romantic image of the modern musician as tasty but troubled troubadour roving from town to town on his lonesome (except for his bandmates, backing singers, roadies, drug dealer and manager, of course) and taking sensual solace where he may is a powerful one, long propagated by he-sluts who would be intimate with a jack-in-the-box if it looked at them the right way. But there is another sexual cliche which musicians go in for when the ceaseless sexual smorgasbord causes a bilious attack and they think that they might want to set up something a little more a la carte. And then – just as men traditionally had it off with their secretaries rather than roam too far from home – they may turn to a bandmate. You might call them ‘randmates’.

In his 1995 autobiography Take It Like a Man, Boy George wrote of his relationship with drummer Jon Moss as being ‘built on power-tripping and masochism’ adding that ‘our love, however diseased, was the creative force behind Culture Club’. Recently Moss was awarded a reported £1.75 million to be paid by his erstwhile bandmates for ‘lost earnings’ after being told to stand down from the band’s 2018 European tour when the aftermath of the ‘great unresolved romance of the century’ (as Moss once called it) proved too tense.

Just as men traditionally had it off with their secretaries rather than roam too far from home, roving musicians turned to a bandmate. You might call them ‘randmates’

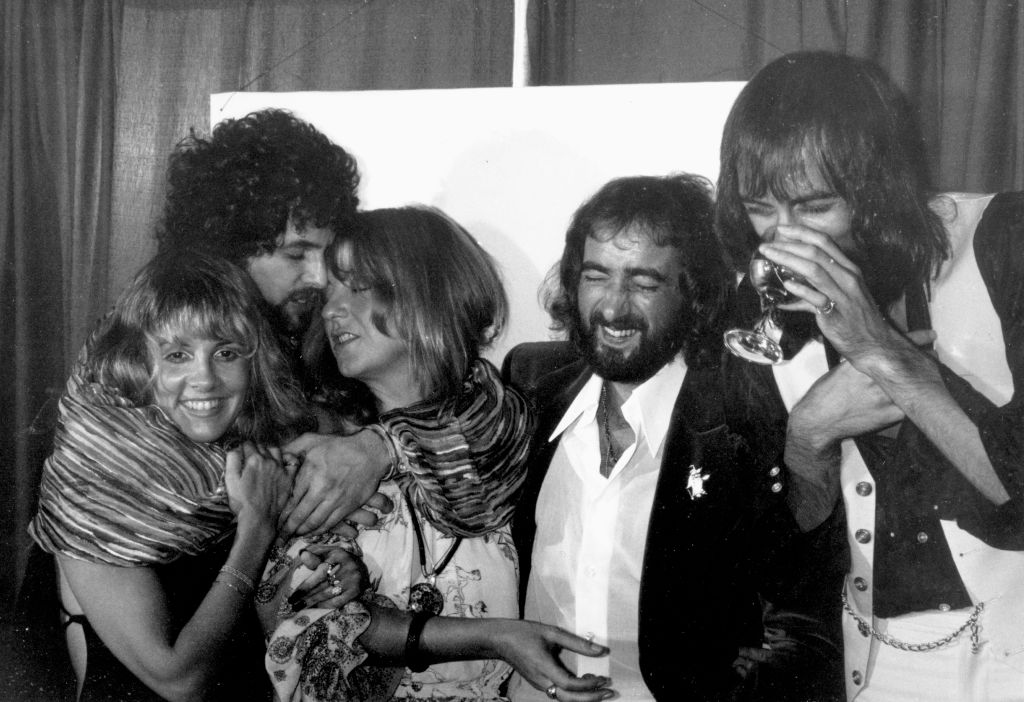

Over on Amazon Prime, the TV adaptation of Daisy Jones and the Six (based on the best-selling novel based on the best-selling and band-romancing Fleetwood Mac) is a smash hit. There was a point when Fleetwood Mac resembled nothing so much as a sex-shop version of Twister; how clever they were to capitalise on this by recording Rumours, the album which went on to sell more than 40 million copies – the 12th best-selling album of all time.

Though Rumours was issued in 1977, Fleetwood Mac were a product of the 1960s, and the love-the-one-you’re-with ethos of the time perhaps made shrewd boyfriends or girlfriends of a talented singer or musician think it wisest to tag along and keep an eye on them – thus the Mamas and the Papas and Jefferson Airplane. Cher was lumbered with her older and less talented husband Sonny, while Tina Turner suffered ceaseless violence from her loathsome husband Ike.

Punk defined itself largely by hating the hippies of the 1960s, and in many ways acted as a sexual corrective to the decade; there were far fewer groupies and far more friends-of-the-band-with-benefits. Similarly, the inter-band relationships were far more likely to be between partners (a ghastly word unless used of people who are a) playing tennis, b) have a law firm or c) have an extremely dull sexual dynamic leading to the situation where one of them doesn’t want to marry the other) rather than cash-cow and plus-one. Talking Heads’s Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth (now married for 45 years) epitomised this new way of band-romancing – though it sometimes felt like there were three of them in that marriage, Weymouth’s wide eyes never leaving the whirling David Byrne as her hapless husband bashed away at his drum kit, safely stashed away at the back of the stage.

Blondie’s Chris Stein and Deborah Harry were a far more appealing pair; as with Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller before them, they represented the bookish Jew’s eternal appeal to the blonde sexpot. Harry writes of her alliance with Stein: ‘We kept on making it for 13 years. I didn’t think it could be done. But it was so easy.’ When Stein developed a rare and potentially fatal autoimmune disorder, which took him three years to recover from, Harry devoted all her time to him, leaving them both impoverished – a very rare example of sex, drugs and rock’n’roll mutating into selfless devotion.

In the post-punk world, band-romancers became the norm: The Fall’s Mark E. Smith and Brix; Brett Anderson and Justine Frischmann; New Order’s Gillian Morris and Stephen Gilbert; Tracey Thorn and Ben Watt; Phil and Joanne from the Human League; Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore; the wonderful White Stripes. The teenage Gwen Stefani came to fame in the pop group No Doubt, whose first hit Don’t Speak dealt with the break-up of her love affair with a bandmate, the video very much recalling the way Abba (the greatest randmates of all time) would dramatise their real-life heartbreak in search of the perfect three-minute MTV-friendly kiss-off.

Why do band-romancers do what they do, knowing perfectly well that nothing kills a friendship like a busted romance – and how hard it will be to work sensibly, even after the dust settles, alongside someone who has made you feel the best and the worst you’ll ever feel? Well, watching somebody do something well is often sexy, and you’ll be seeing it in close-up – of course, there are unexplainable anomalies here, like the Eurythmics. But generally looking at someone being screamed at by a cast of thousands while wriggling about within grabbing distance of oneself may make one recall the old Paul Newman line about his marriage to Joanne Woodward: ‘Why go out for hamburger when I have steak at home?’ Nobody really knows what a rock idol feels except another who has a similar experience of what Janis Joplin described as ‘making love to 25,000 different people – then I go home alone’.

To bring us back to the squabblers of Culture Club, an extra layer of pressure is added when homosexuality raises its head; think of the Runaways’ Joan Jett and Cherie Currie keeping it quiet lest they put off the teenage boys who were thought to be their main audience. Knowing what we know now, of course, it’s likely that this would have made their audience even keener – as would the disputed liaison between Spices Scary (says it happened) and Ginger (denies it). But there’s also the aspect that because so many relationships between young men in bands are so intense and immature anyway – hilariously embodied in Spinal Tap’s David and Nigel – there already appears to be some sort of love affair taking place; Lennon/McCartney, Jagger/Richards, Morrissey/Marr. When they combust, the same anger, recrimination and loss experienced by the bed-hoppers of Fleetwood Mac is often acted out. Anyone watching the way John behaved with Yoko, leading Paul to do the same with Linda, could easily imagine that the two ex-Beatles were also ex-lovers, due to the way they paraded their new partners around, right into the recording studio: ‘Don’t need you now – look, I’ve got a new friend and she can play the tambourine!’

Are the great days of band-romancers over? Probably. The issues of consent and coercion have, understandably, reached even the notoriously sluttish shores of rock and roll (a term which started out as slang for sex) and what may seem a good idea after a bottle of Jack Daniels with applause still ringing in one’s ears may feel less so in the cold light of a motel morning. And then there’s the undeniable fact that – in common with culture generally – popular music is so much less sexy than it used to be. Hearing a David Bowie record the other day, I had the feeling that were he to start out today – even though he more than anyone ticks all the gender-fluid and non-binary boxes – he wouldn’t be made a superstar by today’s anxious youth; he just looked like he was enjoying it all too much.

In a musical era where childhood-sweetheart-marrying Ed Sheeran is king, there’s no call for a queen bitch – or for Fleetwood Mac, still warm from their adulterous water-beds. So, when we look back on the band-romancers of the 21st century, it’s a drab fact that the greatest union we will recall is that between Sam Smith – and Sam Smith.

Awful People – a play by Julie Burchill and Daniel Raven about sex, drugs, race and class – will debut in the Brighton Fringe Festival from 22 to 25 May. You can book your tickets here.

Comments