Juliet Townsend finds that children’s arcane playground rituals have survived television, texting and computer games

When Iona and Peter Opie published their groundbreaking work The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren in 1959, they started their preface by pointing out that

Queen Anne’s physician, John Arbuthnot, friend of Swift and Pope, observed that nowhere was tradition preserved pure and uncorrupt ‘but among School-boys, whose Games and Plays are delivered down invariably from one generation to another.’

Theirs was the first study to establish that this was still largely true in the mid 20th century. Steve Roud now brings the story up to date, and seeks to find out whether this rich oral tradition has survived the onslaught of computer games, texting and television.

He is the first to acknowledge that he could not duplicate the sheer scale of the Opies’ field research, which involved 5,000 children, 70 local authorities and all types of schools throughout the country. It appears that he has had direct contact with a relatively small number of individual children and schools. On the other hand, he has had access to the internet, through which he has garnered a rich store of contributions, especially from adults remembering the games and rhymes of their own childhoods.

Roud points out that for more than a century writers have bewailed the fact that ‘children are forgetting how to play’, blaming city life, the cinema, television or computer games, according to the date and the perceived threat. Actually, children’s play thrived on city streets and in playgrounds, and the stars of the cinema, television and pop music were effortlessly absorbed into their rhymes and games, from ‘Charlie Chaplin sat on a pin, How many inches did it go in?’ to ‘I’m Popeye the Sailorman, I live in a caravan’ or the more abrupt ‘Jingle Bells, Batman smells’.

Perhaps the most important revelation of this book is that children today, compared with those in the 1950s, are abandoning their games at an ever earlier age. Whereas 50 years ago the Opies noted children regularly playing games like Kick the Can and Wavie well into their teens, Roud has found that today these, together with skipping and clapping games, come to an abrupt halt when children transfer to secondary school at 11.

The result of this is that some games, particularly those requiring complex strategy, have become simplified and debased to suit the abilities of children aged ten rather than 14. It is a pity that he did not include private schools in his study. Prep schools, where children remain until 13, may well preserve much that has been lost elsewhere.

Roud says in his introduction:

What I have set out to do is to disprove the pessimists who think children no longer play, and show how games have been endlessly modified and reinvented, or sometimes abandoned and replaced, over the last century.

In this he succeeds, but, although much of interest remains it is still a picture of decline. Nowadays there is simply not the opportunity to build up the skill and cunning demanded by many games that were at their peak at a time when most children spent hours every day playing in large groups in the street or fields.

Nonetheless there is much that is reassuring in this book, which shows the resilience of childhood traditions. Children are neither scholarly nor politically correct, and references to Coca-Cola or spacemen crop up in rhymes whose essentials go back for centuries, while poor Ching Chang Chinaman has been subjected to an ever-changing series of disasters over the years.

One thing that has never faltered is children’s fascination with what Roud calls ‘gross subjects’:

If you see a bunny

With a runny nose,

Don’t think it’s funny

Coz it’s SNOT.

There are many gleefully disgusting visits to the lavatory and the sick bowl, and the human body is followed in unlovely detail from the cradle (‘Mummy, I’m unhappy,/There’s something in my nappy’) to the grave (‘The worms crawl in and the worms crawl out. /They crawl in thin and they crawl out stout.’)

It is tempting to attribute to the rhymes and vocabulary of this oral tradition a greater antiquity and relevance than they actually deserve. I was surprised to learn that some verses which I had imagined dated back hundreds of years were first recorded only in the early 20th century, and Roud wearily refutes the widely held but false belief that ‘Ring a-Ring a-Roses’ derives from the Plague. In the 1960s I found girls in Hoxton, who had never heard of Lord Randal, chanting their own version:

At the time I thought it a fascinating ancestral memory. I now see that it was probably a take-off of what the previous generation had been singing at school.

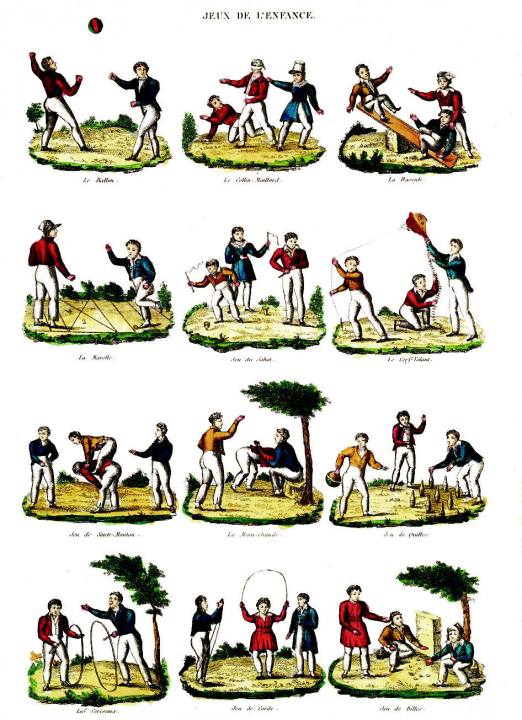

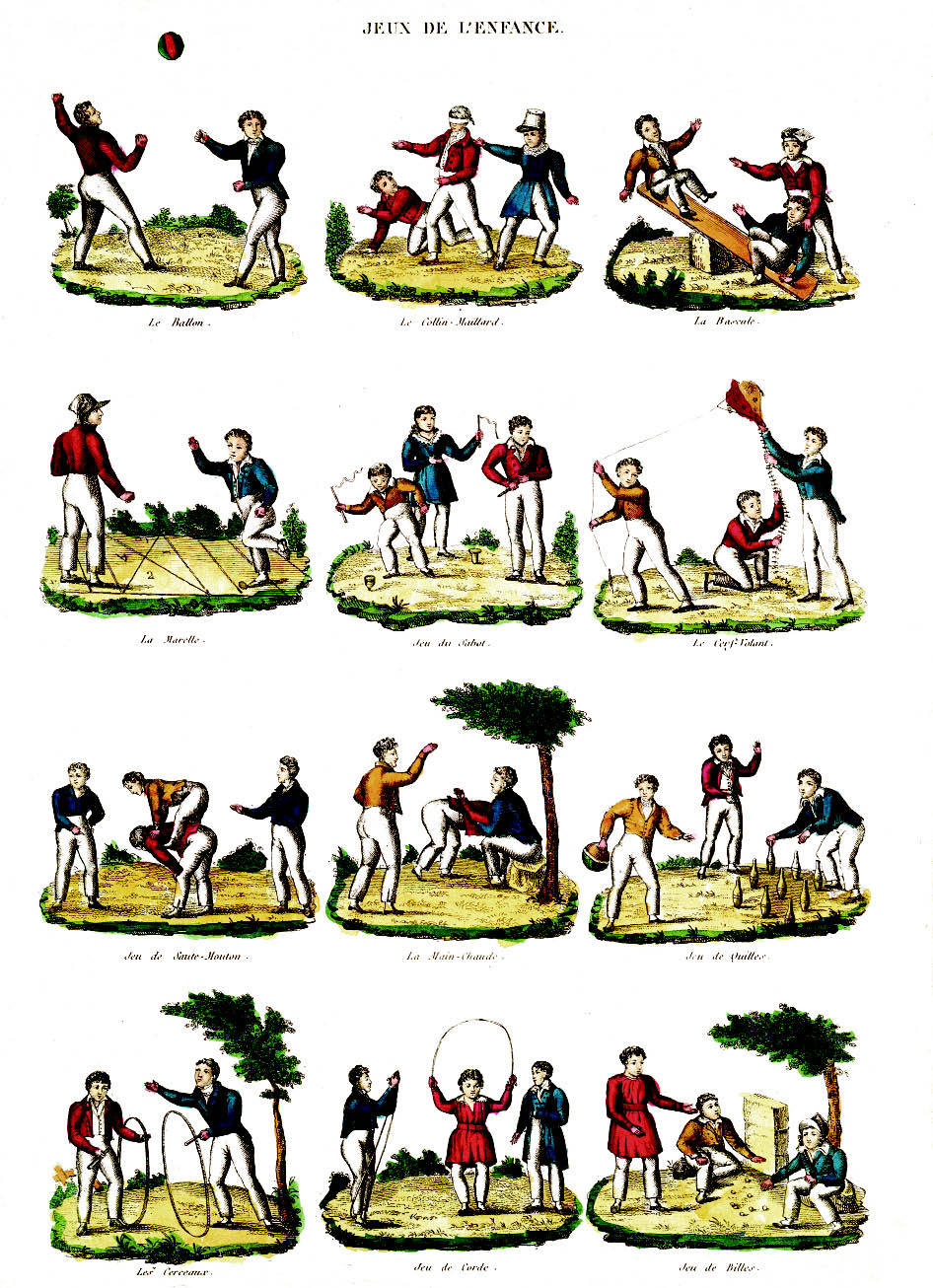

For me the most rewarding part of this book was its detailed account of the rules of many half-forgotten games, from marbles to hopscotch, which even led to my trying out a few lumbering hops last week on the squares of a London pavement.

Childhood is a realm we have all inhabited, and it is extraordinary how a jingle, or the phrase ‘Fains one, touch the ground, amen’, can transport us back to a world of rituals, games and traditions as unbending as those of the Medes and Persians. If you want to make that journey, The Lore of the Playground will certainly point the way.

Comments