Here he comes. Royalty’s favourite crackpot is back. Alan Bennett’s trusty drama, The Madness of George III, doesn’t really have a plot, just a pathology. The king is fine, he then goes barmy, he stays barmy for a bit, he gets bashed about by sadistic healers, then he recovers. It’s less a play and more a monologue amplified by a cast of glove puppets.

Each supporting character is given, at most, two attributes. William Pitt drinks and keeps his counsel. The queen snorts and whinnies like a German weightlifter. Pious equerries proclaim their loyalty. Various doctors wheedle and pontificate. The Prince of Wales, an overdressed slob, waddles in and out sounding greedy. The aristocratic Lady Pembroke trundles around like a wax cleavage in a noose of pearls. And Charles James Fox, one of the most flamboyant figures in English history, is reduced to a posh simpleton with a beer gut. And he wears a beard too, which, in the 1780s, would make him a pirate or a convict. Toffs didn’t sport whiskers until after Crimea.

The sets in Christopher Luscombe’s stylishly vacuous production are made from gilded picture frames nailed on to mobile flats. Gastropubs use the same motif to suggest forgettable elegance. Every single costume is as pristine as a freshly unwrapped bandage. Gowns, uniforms, frocks and tunics are all spotlessly neat, and ironed flat, as if the show has been hired from a museum and is due back tomorrow, at noon, in mint condition. It feels very remote, unlived in and not quite human.

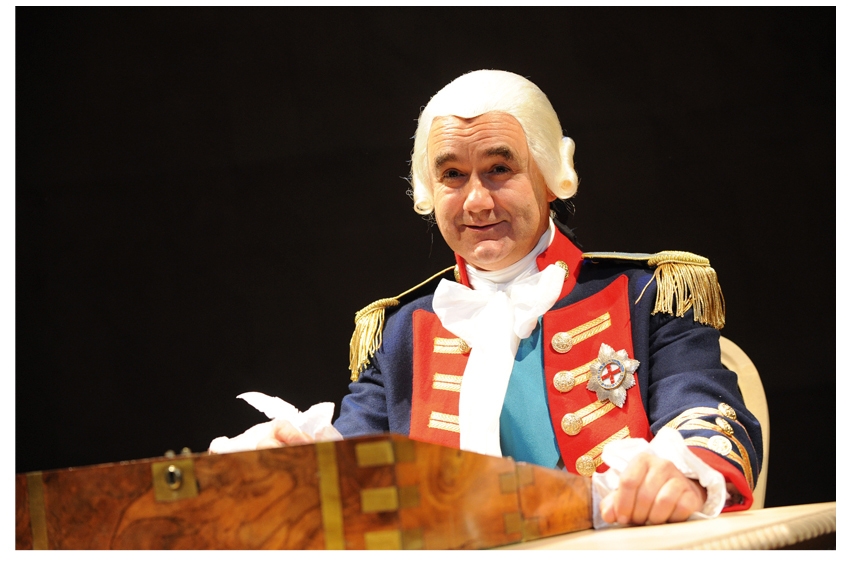

David Haig, born with the gift of eternal middle-age, is well cast as the innocuous nitwit charged with the job of running an empire without losing any of the important bits (like America). But the most striking thing about the production is its popularity. It arrives in the West End after a punishing national tour and, on the evidence of the mid-week show I saw, the public’s appetite for punishment is undimmed. It was almost sold out. How come?

The combination of majesty and disability is strangely appealing (as we saw from The King’s Speech and from Meryl’s Oscar-tipped impression of Lady Thatcher as a vegetable-in-waiting). And the play’s premise, that any old moron could be quite a good king, is rather flattering. Most importantly, the script is a counterstrike against liberal posturing and theatrical experiment of every kind. It’s the most overtly Conservative drama of the 20th century, a gormless and unquestioning celebration of crown, flag and anthem piped to the heavens and cheered on by the servile suburbs.

The Almeida has come up with a new version of Lorca’s piping-hot melodrama, The House of Bernarda Alba. In Bijan Sheibani’s production, the show has been bundled out of 1930s Spain and dumped in an unnamed Iranian village in 2002. Dunno why. Extraordinary rendition is never good for plays. It destroys their health. And for every similarity between hard-line Spain and basket-case Iran there are three or more incongruities. The result is a working seminar not an entertainment, a comparison of footnotes, a laborious evening spent labelling cultural observations. You watch under constant threat of ‘the interesting juxtaposition’.

Sheibani overlooks the script’s crowd-pleasing intensity and goes for languor, atmosphere and elegance instead. Some of the lighting effects are gorgeous but there’s only so much time you can spend looking at a nice lamp. The action constantly grinds to a halt so that another long, long minute of aching poignancy can lumber past. (There were so many yawns being stifled that the contagion spread across the stalls and triggered a Mexican wave of boredom.)

The acting does little to help. The matriarchal tyrant Bernarda Alba (good Islamic name, that) is played by Shohreh Aghdashloo, a beautiful actress whose tremulous presence is at its most effective when she says nothing. Her insecurity with English removes all conviction from her performance. For some reason she has an Americanised drawl, while her daughters and her servants all talk like Hampshire stockbrokers on horseback. A very odd blend of influences. The furniture is neither Spanish nor Islamic but solid Victorian oak stuff on loan, no doubt, from an Islington antique shop.

The show’s best feature is the red-blooded Hara Yannas (Adela), who brings a welcome sense of erotic revolution to her mother’s hellish paradise. Her sister Elmira is powerfully played by Amanda Hale despite being horribly miscast. Elmira is a hunchbacked dwarf and Miss Hale is a willowy Home Counties beauty. Bit of a problem. So they taped a rugby ball to her shoulder blades and prayed that she’d double over and become repulsive. Result: the sexiest cripple you’ve ever seen.

Comments