Alexei Navalny, the de facto leader of the demonstrators who thronged freezing Moscow on Christmas Eve, minces no words. On rospil.info, a website he founded that is dedicated to the investigation of local and municipal corruption, he introduces the topic like this: ‘Why is all of this necessary? Because pensioners, doctors and teachers are practically starving while the thieves in power buy ever more villas, yachts, and the devil knows what else.’

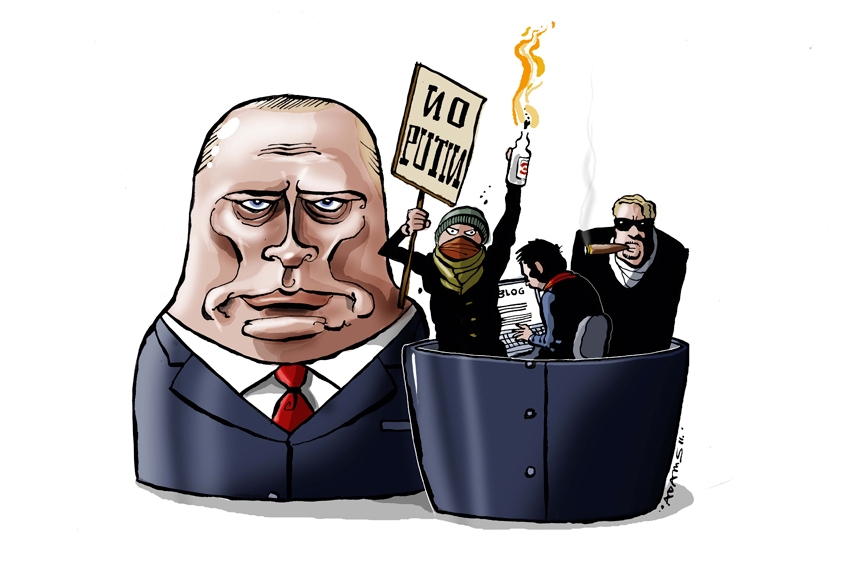

Nor does Navalny shy away from sharp visual imagery. Another one of his projects is to collect photographs of potholes, crumbling motorways, cracking bridges and other road catastrophes waiting to happen. On his personal blog, where he posts running commentary on the nefarious activities of Russia’s most famous corporations and covers the protest activities of himself and his supporters (demonstrations, lawsuits, prison), Navalny uses a particularly arresting photograph on the top left corner of every page. It shows a large, furious, red-faced man. The man is brutally strangling an equally massive, equally red-faced opponent.

The photograph is apt, for Navalny is the first real post-Soviet dissident. He is protesting against the recent falsified parliamentary elections, and he is angry. His fans and online followers are angry too. All of Navalny’s sites routinely refer to Russia’s business and political leaders as crooks, bandits, criminals and thieves. They also contain clear information about how to complain to the authorities about corruption or sloth, and about how to proceed if the complaint isn’t acknowledged. They are deliberately transparent — rospil.info lists its bloggers and legal advisers by name — and they contain a good deal of technical, legal information. At his photo project, the rules and regulations governing road repair and safety are listed in full.

Navalny, his colleagues and his followers differ from a previous generation of Russian democrats. The dissidents left over from Soviet times — the chess champion Gary Kasparov, the human rights activist Ludmilla Alexeeva — already seem to belong to another era. Even the founders of Yabloko, Russia’s anaemic liberal party, seem grey-haired and boring by comparison.

Part of the difference is simply age. Navalny was born in 1976. He was nine years old when Mikhail Gorbachev came to power. He was 15 when the Soviet Union broke up for good. He has lived his entire adult life in post-Soviet Russia. No wonder his thuggish style and occasionally vulgar language seem so perfectly in sync with the thuggish and vulgar society around him. No wonder they seem an appropriate response to Russia’s thuggish and vulgar leadership.

But the more important difference lies in his methods and his focus. As the death this month of the great Vaclav Havel reminded us, the resistance to communist totalitarianism took mainly intellectual, literary and theoretical forms. Much of what was most important could be discussed around a kitchen table. By contrast, Navalny’s resistance to Putinist authoritarianism is specific and practical, and much of it takes place online. Despite some allusions to the dissidents of the past in recent days — one Moscow demonstrator carried a ‘We need a Havel’ placard and others are calling for ‘a new glasnost’ — Navalny doesn’t talk much about human rights. Until recently he didn’t talk much about democracy, which many Russians dismiss as an empty ideal. Instead, he talks about money: who has it, who has stolen it, who has misused it.

And this too makes sense. Contemporary Russia is a materialist, non-ideological society. It’s hardly surprising that the first political opposition movement to take a materialist, non-ideological approach has had so much success. Navalny is right to focus on what people care about. Once upon a time, Soviet dissidents worked to expose the hypocrisy of a regime that claimed to believe in peace and justice, and in fact promoted war and terror. Navalny and his ilk work to expose the hypocrisy of an authoritarian clique which claims to be making everyone richer but is in fact stealing most of the nation’s money for itself.

So far, the official response to Navalny has been careful and cautious, but that should not be surprising. Though the Putinist regime is sometimes mistakenly called ‘Stalinist’, it has never been a true totalitarian regime. Its borders and its satellite channels are open, its internet is ineffectively policed and it has always tolerated some limited dissent. Although most Russian television stations are controlled one way or another by the Kremlin, a few newspapers have always been allowed to publish critical articles, so long as their circulations remain low. Alexander Lebedev, owner of the crusading Novaya Gazeta of Moscow (as well as the Independent and the London Evening Standard in this country) reckons the authorities allow his newspaper to function simply because they themselves want something decent to read. ‘They want to know what’s going on too,’ he once told me.

A few critics, Kasparov among them, have also been allowed to keep going, bar the odd jail sentence, presumably because they are not terribly effective. More dangerous critics have met worse fates. The defiant oil baron Mikhail Khodorkovsky is now in a Siberian prison camp. The crusading journalist Anna Politkovskaya was murdered on her doorstep. The lawyer Sergei Magnitsky was tortured to death in prison for refusing to withdraw accusations of corruption.

Until now, the authorities appear to have put Navalny in the Kasparov category. At first glance he must indeed have seemed like yet another oddball, a person who could inspire 5,000 people to take to the streets but not 50,000. When I met him last winter, he was introduced to me as a prominent blogger, not as a candidate to run a political movement. Even now, in the wake of several major street demonstrations, Putin’s entourage may well be hoping Navalny’s star will fade. The population of Moscow is more than 10 million, after all, and the best estimate for last week’s rally is 80,000 — still a drop in the bucket. They may well be counting on the cold weather to discourage further action.

•••

Two tests now lie ahead. The first is of the nascent Russian middle class, which has given so much online support to Navalny and his colleagues. But it is one thing to join a Facebook campaign, quite another to have your face smashed into a wall. Will the demonstrators keep showing up in large numbers? Do they have a following outside the Russian capital? Can they withstand the brutality of which we already know the Russian riot police are capable?

If the answer to the above is yes, then the second test is of the authorities: how far will they go to stay in power? The current leadership has a lot to lose — billions of dollars, principally — and many of its members will fight hard to keep their status. Their fortunes were acquired through political connections and they can lose those fortunes through politics too (just ask Boris Berezovsky). Some of them can escape to their homes in London, but some need to remain in Russia. It may not suit them to share their country with an anti-corruption activist such as Navalny. A diplomatic acquaintance of mine recently asked Navalny if he and his family were prepared for the consequences of his protest. Yes, he replied, he understood: perhaps a long prison sentence on trumped-up charges. Perhaps an ‘accident’ in a car or plane. Or perhaps an internet firewall will suddenly make his websites disappear.

Then what? In the wake of a serious clash between the authorities and protestors, a violent revolution is not impossible — though it is unlikely. Fear of anarchy is a part of Russia’s national

genetic code. Memories of the chaotic 1990s, when pensioners, doctors and teachers went unpaid for months on end, are still fresh. The most radical protest leaders, among them the Left Front leader Sergei Udalstov (now serving yet another in a series of multiple prison sentences), have galvanised some support in Moscow but are unlikely to inspire confidence in the provinces of a nation suspicious of anything that sounds too much like rapid change.

If the inner circle ever decides that Putin himself has become a liability, a palace coup is also possible. Mikhail Prokhorov — a nickel billionaire who is number 32 on the Forbes ‘richest’ list, owner of the New Jersey Nets basketball team and a clear beneficiary of the current system — has declared that he might be a candidate in presidential elections, and he may well see himself as Putin’s heir. He has a few things going for him: having already acquired his money, he would not need to steal. But the very wealthy aren’t particularly popular in Russia at the moment (Putin goes to great lengths to hide his own fortune) and it isn’t easy to see Prokhorov as a populist reformer. The incumbent president, Dmitri Medvedev, is similarly tarnished by his associations with the Putin regime. Nobody likes a front man, to put it bluntly, even the one assigned to the role of Mr Nice Guy.

Other scenarios are gloomier still. In the event of a real crisis, if another social breakdown suddenly looms, and the regime is able to blame the chaos on its opponents, then the country may unite behind Putin once again. If they learned nothing else from the 20th century, Russians learned to beware of politicians making extravagant promises. All things being equal, they may prefer the devil they know.

But we aren’t at a crisis point yet — not even close — and so far this is an extraordinarily positive story. For the first time in 20 years, protestors have organised two large and largely peaceful demonstrations in Moscow. If nothing else, they prove that Navalny and others really have begun to create a new kind of opposition, using a new kind of rhetoric; that Russians do care about how they are ruled; that some are even willing to do something about it. One of the world’s most corrupt and self-satisfied regimes has been embarrassed, which is always a good thing. Navalny’s achievements are impressive, and they are real. It’s just that he hasn’t yet pointed the way to what comes next.

Comments