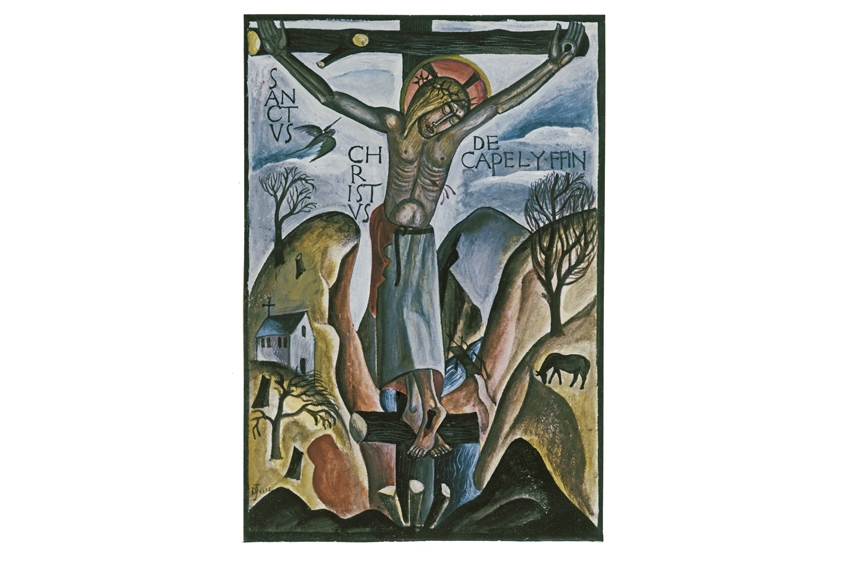

As the focus for an Easter meditation, David Jones’s ‘Sanctus Christus de Capel-y-ffin’ (1925), a small, heartfelt painting in gouache on paper, could scarcely be bettered. The Crucifixion takes place in a luminous landscape with the bird of hope in attendance. This is the world of medieval illuminated manuscripts and ivory carvings, a highly sophisticated spiritualised and classicised vision of existence that is sometimes dismissed as primitive. A Welsh hill pony is set off against a chapel, trees and a bridge over running water in an arabesque design quivering with natural and spiritual life. Rhythm is crucial. As Jones said, ‘I don’t care how static the subject is, but it must be fluid in some way.’ He recognised the strong rhythms of the Welsh hills and the counter rhythms of the brooks, and made of them a new unity, a new beauty.

David Jones believed that the artist’s primary function was as a ‘rememberer’. In 1959 he wrote: ‘My view is that all artists, whether they know it or not, whether they would repudiate the notion or not, are in fact “showers forth” of things which tend to be impoverished, or misconceived, or altogether lost or wilfully set aside in the preoccupations of our present intense technological phase, but which, nonetheless, belong to man.’

Myth and religion were two of the things he strove through his art to elucidate to the contemporary mind. He was lucky to have been born at a time of late flowering in Catholic culture: not only were the writers G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, Evelyn Waugh and Graham Greene superbly active, but Eric Gill and his circle of artists were Jones’s intimate friends, while the spiritual overseers included that notable Jesuit Father Martin D’Arcy, together with Douglas Woodruff and Tom Burns, successive editors of the influential Catholic weekly The Tablet. In such a sympathetic climate, Jones could thrive and give rein to his very particular themes and obsessions. His friend and fellow-poet Kathleen Raine identified the three strands in Jones’s work that defined his place in civilisation: Wales and the Romano–British roots of our ancestral heritage; the Catholic Church and its liturgy; and the army.

David Jones (1895–1974) was born in Kent of Welsh extraction, his father hailing from Flintshire, while his mother’s family came from Rotherhithe. He was four when he first visited his grandparents in Wales, and from his earliest years drawing made more sense to him than anything else. He studied at Camberwell School of Art under A.S. Hartrick, and then on 2 January 1915 enlisted in the Royal Welch Fusiliers, fighting as a private in the trenches of the Western Front from December 1915 to March 1918. The camaraderie of the army was one revelation, another was the mystery of the Eucharist, first glimpsed during the war through a crack in the wall of a barn while Mass was being celebrated.

After much soul-searching he was received into the Catholic Church in September 1921, and in 1922 he joined the community set up by Eric Gill at Ditchling in Sussex, to concentrate on establishing a career as an artist-craftsman. To this end he learnt the technique of line engraving.

Gill left Sussex and gravitated to Wales, re-establishing the community in 1924 at Capel-y-ffin in the Black Mountains. In 1925, Jones joined him there, staying on and off until 1927. These were crucial years in his development, which saw his first works as a mature artist, among which this small but potent Crucifixion must be numbered. Just across the valley from the community was Y Twmpa, or the tump, a conical mountain that features in many of Jones’s paintings of this period, becoming a motif rather like Cézanne’s Mont St Victoire in its importance to the artist. It appears here in the background of the Crucifixion, to the right of the Cross.

Jones loved lettering — an enthusiasm he shared with Gill — and became an expert maker of inscriptions. In this painting he has lettered the legend ‘Sanctus Christus de Capel-y-ffin’ around the figure of Christ in the top half of the painting, arranging the script to make both horizontal and vertical patterns of strikingly original simplicity. His was a sacramental vision of celebration and praise, based on an understanding that transient natural beauty was but a reflection of eternal things. As Auden wrote of William Blake, he ‘heard inside each mortal thing / Its holy emanation sing’. In his art, David Jones proceeded from the known to the unknown, rediscovering the sacred in the ordinary.

Although Jones was one of those rare figures who excelled in more than one discipline, and is widely known and respected as a poet (Eliot placed him alongside Pound, Joyce and himself as one of the four significant writers of his generation), he thought of himself essentially as a painter rather than a writer. Ironically, he is still somewhat underrated as an artist, whereas his reputation as a poet is more assured. But in whatever he attempted, his profound historical imagination was evident, much preoccupied with the layering of metaphysical, mythical and metaphorical meaning. For Jones, man made things of mysterious and sacred significance, which were both timeless and yet also of their age, possessing what he called a ‘requisite nowness’.

Jones hated the way daily life was deprived of spiritual meaning. What would he have made of our secular society? As Kathleen Raine so poignantly put it, ‘The ugliness of the world without any sacred dimension, proliferating and submerging the landmarks of the soul, was more than he could bear.’

At the Solemn Requiem for David Jones held in Westminster Cathedral, the poet Peter Levi delivered a sermon that began as follows: ‘David Jones understood better than the rest of us the sacrifice of the lamb. His experience in the 1914 war was terrible and it was deep. He understood and he needed what is offered at the stone of this altar and what is shared at the table of this altar and what is said and what is sung in the petrified forest of this church. His need was quite innocent, merely human, to do what has already been done once and for all on another hilltop, outside a different city, and also done many times from the beginning of mankind. In its reality and in its

meaning that long series of sacrifices has not ended.’

There is in this serenely joyful painting a sense of a world washed clean and a new beginning for mankind.

Comments