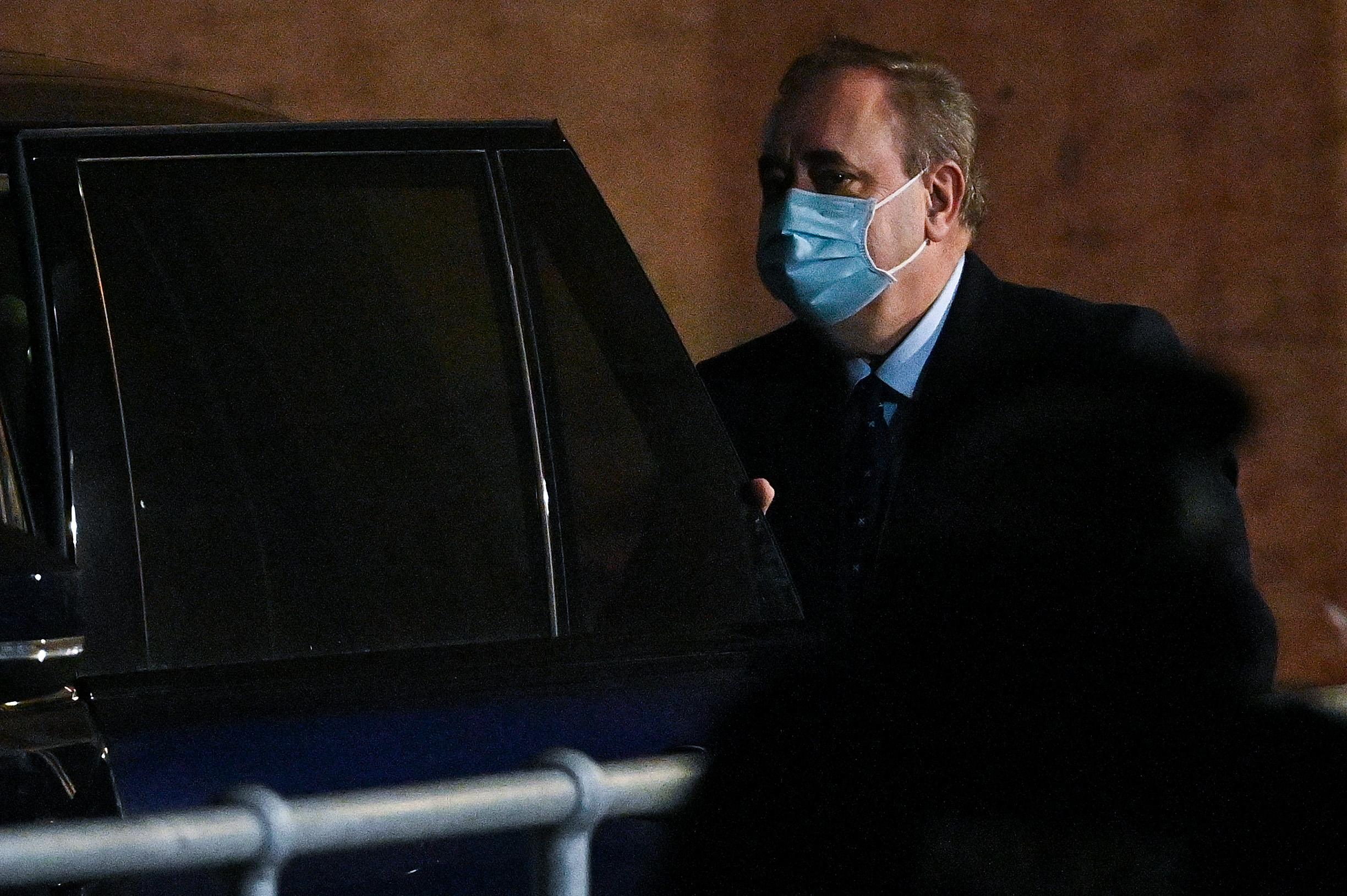

As Alex Salmond finally testified before the Scottish parliament on Friday, it was clear that he was trying to walk quite a fine tightrope.

On the one hand, the former first minister is alleging a conspiracy so vast that, if true, it would deeply discredit the central institutions of the devolved Scottish state. His claims put the reputations of the Scottish government, the Scottish parliament, and the Crown Office, not to mention the civil service and even the police, on the line.

Yet he shrank from the implications of this. Right from the start, he sought to erect a firewall from the leadership of these institutions and the institutions themselves: ‘The Scottish civil service hasn’t failed; its leadership has failed. The Crown Office hasn’t failed; its leadership has failed.’

Cosy consensus has been a feature of devolution in both Edinburgh and Cardiff

It’s understandable that Salmond is wary of seeming to side with those who claim that Scotland risks becoming, in his words, a ‘failed state’. His remaining supporters would likely take a dim view of his seeming to ‘talk Scotland down’.

Some on the other side of the constitutional question have not been so reluctant. The Spectator’s editor Fraser Nelson has written about how the scandal has shaken his original belief in the creation of the Scottish parliament. George Galloway has gone even further and outright called for its abolition.

Whatever his faults, Galloway is an able political operator and he’s currently trying to corner the hard-line Unionist vote. His public conversion to abolition might therefore be significant. Not because it presages a sudden upsurge of devolution sceptic sentiment among the general electorate, but because it might become a bigger, and problematic, factor in Unionist politics.

This has already happened in Wales where abolition currently outpolls independence. The new ‘Abolish the Welsh Assembly’ party may not yet have broken through in an election, but it is already reshaping the debate by forcing the Conservatives to pivot against the Cardiff Bay consensus in order to try and shore up their pro-UK flank. Their old plan for a pact with Plaid Cymru is now impossible to deliver.

Galloway’s vehicle, Alliance for Unity, is not yet polling so well as Wales’s Abolish party and is ploughing less fertile soil. But there is nonetheless a constituency for his new message. A substantial share of Tory voters remain unreconciled to the Scottish parliament. Perhaps that’s why Salmond’s painstaking attempts to separate his attacks on the ‘leadership’ of pretty much every significant institution of the devolved state from any implied judgment on those institutions themselves made him sound so much like a Scottish Conservative spokesperson.

Like Salmond, senior Tories keep trying to damn the outcomes of the system without damning the system itself. Sure, the system might not have delivered good policy outcomes on such trivial issues as education and the economy. Certainly, devolution may have turbo-charged separatism. Of course, it may have fostered a political culture which is, in the words of one Tory MSP, ‘awash with corruption’.

But, both Salmond and the Scottish Tories insist with a wary eye on their restive grassroots, none of this discredits the institutions themselves. Apparently no experience can. All that’s needed is a change of leadership. Where else did we hear that today?

The problem is that such firewalls are almost impossible to maintain. Salmond must know this — after all, the SNP are past masters of pinning unpopular policies or individual politicians on the structural shortcomings of the United Kingdom. It has been obvious for some time that he is past caring that his campaign against Nicola Sturgeon risks undermining the separatist cause, but it is nonetheless striking to see him advancing an argument that implies Scotland is not fit for independence.

Likewise, on the other side of the table, it will be increasingly difficult for Labour and Conservative MSPs to try and justify solutions based on further tinkering with the British state — the much-feared ‘constitutional convention’ — while continuing to avoid hard questions about the increasingly obvious shortcomings of their own devolved domain. Not least if Galloway starts asking them.

It was not the intent of Salmond or his inquisitors to give devo-scepticism a shot in the arm. But cosy consensus has been a feature of devolution in both Edinburgh and Cardiff (often piously contrasted with Westminster’s more adversarial model) and the result has been insufficient scrutiny and inadequate delivery. A shot of anti-system politics might be just what that system needs.

Comments