This is an important, authoritative work of art criticism that recognises schools of painters, yet displays the superior distinctions of individual geniuses. Martin Gayford, The Spectator’s art critic, concedes that the identification by R.B. Kitaj, an American painter, of a ‘substational School of London’ was ‘essentially correct’, though in London there was no ‘coherent movement or stylistic group’.The only characteristic shared by London painters has always been merely that they live in London. There have been some influential personal relationships, even cases of a sort of cosiness, especially in the French Pub, the Colony Room and other drinking venues in Soho and Fitzrovia.

In this comprehensive, intimate inspection of the London art scene between 1945 and 1970, Gayford observes that there was a ‘great opening up’ immediately after the war. In that pivotal era, ‘a London art world that had previously been small and provincial turned its attention to what was happening elsewhere in the world’. Artistic dominance had shifted from Paris to New York, but London was becoming increasingly significant.

It takes many years of close-up scrutiny and intense conversations to become an expert art critic. Would-be painters who work hard at their craft are often lonely, need guidance and are glad to confide in a sympathetic, knowledgeable critic. ‘At one time or another,’ Gayford writes, ‘I have met and talked to many, indeed most, of the prominent artists’ discussed in this book.

At the end of the second world war, a new generation crowded London’s art colleges as never before, with new experimental excitement. The young students overcame traditional conservatism and looked to the future rather than the past. Abstract Expressionism was an American creation. According to Gayford, the term Pop Art was a London coinage, but it was in New York that it was produced on a large scale. The majority of painters on both sides of the Atlantic no longer submitted to the academic discipline of drawing from human models and plaster casts. Before long, the difficult technique of drawing was hardly taught at all. Since the first daguerreotype of 1839, few artists used photographs for reference, but there seemed to be no point in attempting to compete with them to achieve realistic figurative art. As Gayford mentions, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Picasso, Rothko, Pollock, Matisse and others succeeded without cameras.

By the mid 1950s, the London Zeitgeist brightened. In the late 1960s, the Menswear Association condemned in vain ‘the codswallop fashions of perverted peacocks’ of the Carnaby Street shops of swinging London. In the meantime, an increasing number of ambitious London painters made an ‘American Journey’, Gayford notes: ‘the mid-20th-century equivalent of the 18th-century Grand Tour’. Like those explorers, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, in the bars of Greenwich Village, the galleries of midtown Manhattan and the sumptuous studios of East Hampton, I encountered avant-garde freedom and the oppression of conformity with commercial artistic dogma, fashion and commerce. Soi-disant and genuine painters were as eager to talk about their aesthetic philosophies, know-how and tax problems as so many patients displaying symptoms of chronic diseases.

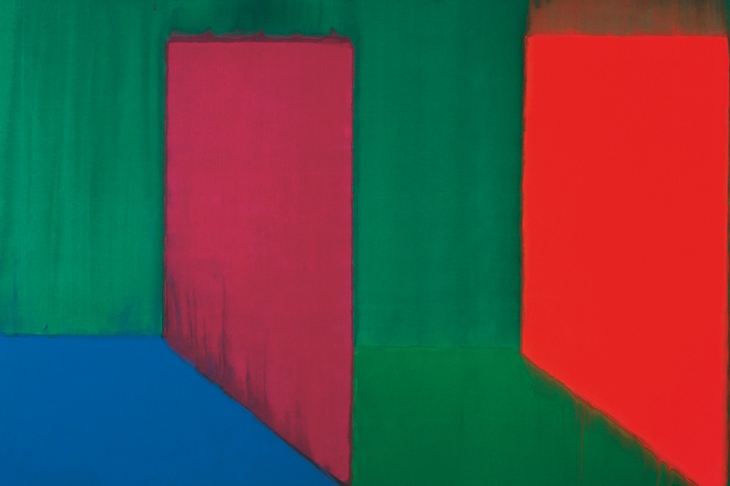

Back in London, fabulously prosperous galleries and auction houses stimulated the painting of countless outsize, gaudy, American-style abstractions. Perhaps in emulation of Andy Warhol, who made a fortune marketing images of soup tins and Marilyn Monroe, in London, too, some enterprising painters and their managers established mass-production art factories. Every profitable innovation attracted many imitations. Action Painting and Op Art were presented as ‘isms’ for all who dared.

Gayford achieved analytical understanding of all sorts of London modernists, from Frank Auerbach to Bridget Riley, and they are all allowed their say, in reports of nice equilibrium. The modernist London painters are interesting in themselves: they added extra intellectual flavour to all the other arts in our bizarre contemporary culture. ‘The major painters of London were all idiosyncratic mavericks,’ Gayford concludes, ‘even when they were modernists.’ The peculiar excellence of this informative survey is exhibited best in passages about the three supermavericks of the subtitle.

David Hockney, Gayford’s co-author of A History of Pictures, having been brought up in a socialist household in Bradford, was pleasantly surprised to be admitted to London’s Royal College of Art. There he was befriended by Kitaj, who praised a sample of Hockney’s draughtsmanship as ‘the most skilled, most beautiful drawing I’d ever seen’. Hockney since then has always boldly asserted his individuality. When he first visited America, he celebrated its free-and-easy customs by dyeing his black hair blond, and he has repeatedly reinvented himself stylistically.

Lucian Freud seemed to develop backwards when he chose to paint figuratively, but he went far beyond ordinary realism, inspecting physiology as penetratingly as if dissecting its musculature. A close friend of Francis Bacon’s, he declared: ‘Francis depended entirely on inspiration, which made him rather brittle. He was completely untrained, and couldn’t draw at all but was so absolutely brilliant that through sheer inspiration he could somehow make it work.’

Bacon’s inspirations were richly varied, including Velázquez, Picasso, William Blake, naked men entwined on a bed, life in the ‘gilded gutter’ and ‘Calvary without salvation’. After oysters and champagne at Wheeler’s in Old Compton Street, he showed me the fertile chaos of his studio in Reece Mews, Kensington, where he said he felt that he was ‘a member of a group of one’. Gayford’s portrayal is tragi-comically wonderfully revealing, and the quotations seem to carry on from David Sylvester’s famous interviews. ‘Ninety-five per cent of people are absolute fools,’ Bacon said, ‘and they’re bigger fools about painting than anything else.’

Comments