Working on a ‘trending’ news desk is the journalistic equivalent of being a battery-farmed hen. When I was still at university, I wrote pieces for one of the most-visited clickbait news sites in the UK, which boasts 300 million followers worldwide. My brief was to pump out a 400-word article in 45 minutes, every 45 minutes, for nine hours straight. My fee for these 12 articles was £125 in total (£13 per hour or, more saliently to a student, a pint for 250 words).

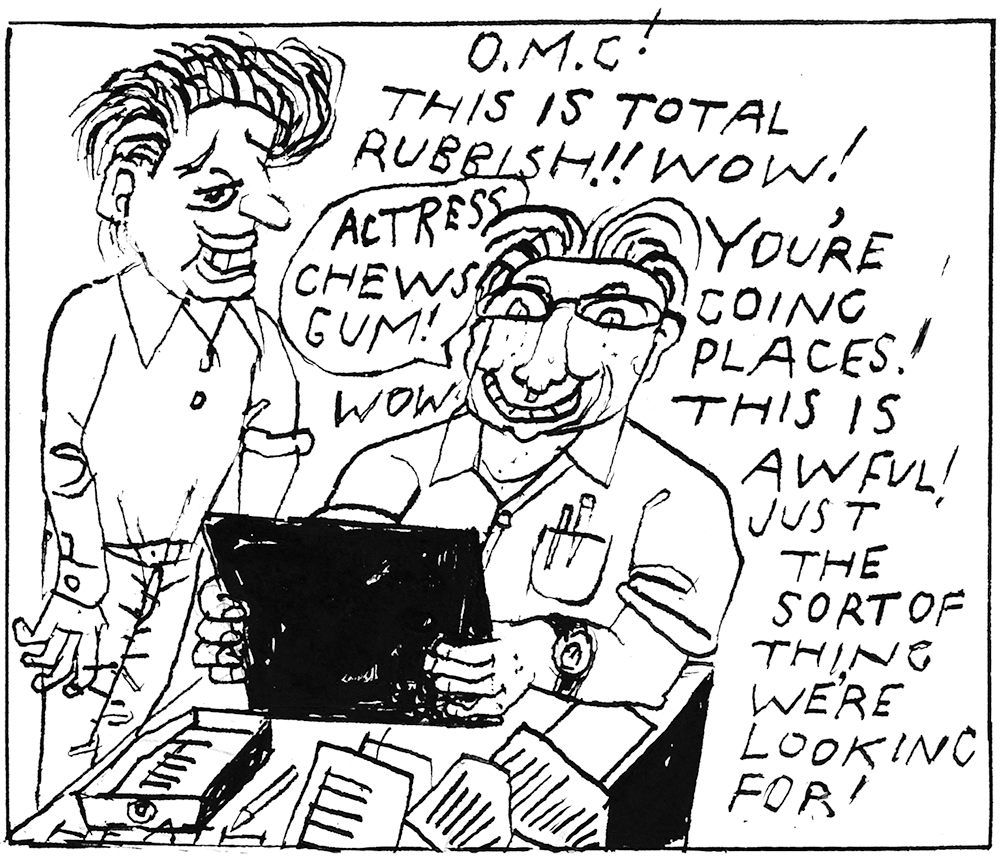

All of you will have come across clickbait online. Some of you might even admit to having clicked on it. Who doesn’t want to know which vegetables are killing you, which celebrities are married to their cousins, or what Victoria Starmer’s beauty regimen consists of (especially given that ‘step five will surprise you’)? In my brief time as a professional clickbaiter I learnt the grim formula for producing an article which over-promises and, 30 seconds of scrolling later, underdelivers.

Who doesn’t want to know which vegetables are killing you, or which celebs are married to their cousins?

The first ‘trending’ news story allocated to me set the tone for my new job: ‘Kristen Bell Said Her Family Farts So Much They Didn’t Smell Rot In Their Home.’ The extent to which this can be described as either ‘newsworthy’ or ‘trending’ is dubious. In the eyes of my editor, it qualified for a story since at least five other online outlets had covered it within the past week.

For clickbait factories, this loose interpretation of ‘news’ has two advantages. Firstly, it removes the need for any fact-checking, research or thought. If you think that 45 minutes is long enough to undertake any original journalism whatsoever on these kinds of stories, then you need a psychological examination.

Secondly, these stories are safe bets in the mindless content churn. Editors can see how much traffic the story attracted on tabloid websites and know that it will generate similar ad revenue on their own platform.

If you find such stories depressing to scroll through, they are equally depressing to write. Clickbait production is designed to minimise the time it takes to get a piece out. My editor would send me a published article. I’d copy it and post it to the site with a tweaked headline. I’d throw in a handful of extra detail and sensationalist adjectives, but the end result would be a reheated version of whatever had graced MailOnline’s ‘sidebar of shame’ a few days before. I suspect my old colleagues can now pump out articles in seconds instead of minutes given the speed with which AI spawns copy. I can only hope the entire clickbait writing process is soon automated, permanently putting these content writers out of their misery.

One of the challenges for clickbait websites is how to keep people reading the article when the stories are so vacuous. The solution is to scrap journalistic ideals such as accuracy, concision and style in favour of what’s referred to as ‘scroll depth’ – the trick of burying the piece’s only nugget of interest so deep in the article that readers might keep scrolling to the end. My subeditor would repeatedly ask me to redraft my work because I had placed useful info too high up in the piece. Perhaps this is a good opportunity for me to apologise to the many readers of ‘Drinking Water From Your Bathroom Could Be Bad For Your Health’, who had to wait until the fifth paragraph for the big reveal.

The content management systems into which I entered my copy are configured to maximise clickbait–friendly yield. A helpful widget in the corner of the screen tracks how many adverts can be crammed into the piece and how many more sentences are required if another needs to be crowbarred in. ‘Search Engine Optimisation’ (SEO), ‘Click-Through-Rate’ (CTR) and ‘Cost-Per-Click’ (CPC) were in the pantheon of sinister three-letter acronyms which determined the value of my writing. If you have ever wondered why online news stories on so many sites are a multimedia minefield of adverts, links and pop-ups, or why you have to battle through paragraphs of things ‘you might also like’ (but almost certainly won’t) only to realise that there was no news buried in the article after all, these acronyms are to blame.

The site I worked for produced clickbait journalism in its purest form, but the weapons in the clickbaiter’s arsenal are wielded to different extents by almost every publication. I doubt there is a news desk in the country unaware of the importance of SEO for getting pieces higher up on Google’s search lists. It’s to be expected that new media groups, which cannot rely on paying subscribers, are the most vulnerable to clickbait’s charms: the lure of quick guaranteed ad revenue is more attractive than introducing a paywall which risks turning away the readership.

This decision is especially easy for editors who lack confidence in the journalistic value of their product. But the pressures faced by ‘legacy media’, at a time when readers are more reluctant than ever to pay for content, helps to explain why even the most established publications are attracted by a clickbait news model – it is no longer the preserve of viral news bots and glitchy regional tabloids. Many broadsheet journalists toil under the glare of a giant LED board providing real-time updates about the online performance of their articles. Perhaps the most depressing thing about clickbait is that it works.

Comments