In 1904, the great Halford Mackinder, founder of the modern academic discipline of geography, published one of the most subversive maps of the century. It might seem unlikely that a scientific representation of the physical world projected according to mathematical principles onto a two-dimensional surface could mess with your head, but that is the unmistakable conclusion of Professor Jerry Brotton’s exhilarating book.

From Hereford cathedral’s Mappa Mundi, with its depictions of enigmatic griffins and bloodthirsty manticores and the Himannopods ‘who creep along rather than walk’, to Google Earth’s satellite view of the world showing it in such detail that the result rivals Jorge Luis Borges’s absurdist vision of a map as large as the earth itself, maps prove to be less conveyors of information than theatrical performances. Indeed the first really popular atlas put together in 1570 by Abraham Ortelius was named Theatrum orbis terrarum. And the influence of Mackinder’s map illustrates how mind-altering the plays can be.

What Mackinder did was to depict the world on either side of the central Asian steppes, locating the United States to the right, as an oriental power, and the vast southern oceans as a counterweight to the immensity of land above. Instead of the Anglo-American view that pictures history and power moving inexorably westward, he offered early 20th-century Europe the chance to imagine that a drive eastward might secure Russia and the landmass beyond, and its master would then have the new American power firmly in his sights.

Adopted three decades later by Rudolf Hess and the Nazis as ‘geography in the service of world-wide warfare’, the vision inflated Hitler’s nationalist greed for Lebensraum in eastern Europe to an immense prospect of global domination. Even today, world strategists, Putin presumably among them, see Russia as the pivotal power on the globe because it occupies what Henry Kissinger called, using Mackinder’s term, ‘the geopolitical heartland’.

Mackinder was only taking to an extreme what every map-maker must do— which is to select a method of representing reality, because it is impossible to reproduce exactly the three-dimensional sphericity of the earth on a flat page. A choice of distortions has to be made: accurate polar regions misrepresent those at the equator, properly sized oceans leave little landmass, the right spatial relationship between Europe and North America diminishes Africa.

In 1569, Gerard Mercator produced the most famous solution to the insoluble problem with a projection that straightened the north-south lines of longitude instead of showing them converge towards the poles. Since the space between them widened in proportion to their distance from the equator, northern countries — those most important in European eyes — were displayed larger than they were in reality.

Because most books about map-making focus on this technical difficulty, treating it as a flaw that must be overcome by increasingly exact observation and clever maths, they tend towards a specialist dryness. For Brotton, however, the inventive possibilities created by cartography’s awkward problem are its chief appeal:

The map’s dissimulating brilliance is to make viewers believe, just for a moment, that such a perspective is real, that they are not still tethered to the earth looking at a map . . . In the act of locating themselves on it, the viewer is at the same moment imaginatively rising above it in a transcendent moment of contemplation, seeing everything from nowhere.

In answer to the question, ‘Where am I?’, the map-maker expects a reader to be split in two.

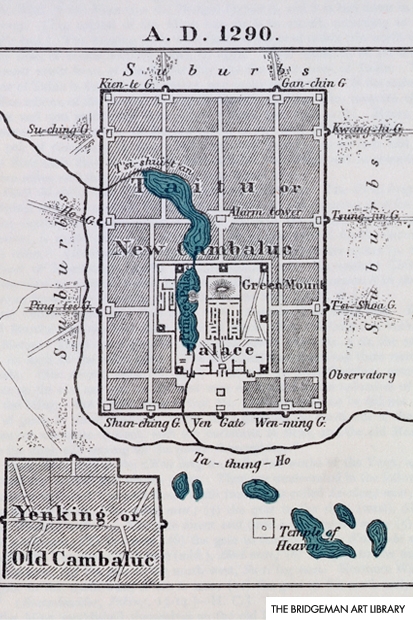

Examined from this bifurcated standpoint, Brotton’s 12 maps are not only records of the changing state of knowledge about the world, but of their composers’ cultural state of mind. A sophisticated attempt by the 12th-century Islamic scholar, Al-Idrisi, to show a globe that he said hung ‘in space like the yolk in an egg’, not only includes information from travellers across the Muslim world, but demonstrates through its borrowing from Greek and Arab astronomers both the tolerance of contemporary Islam, and its belief that faith and science were not incompatible. The 13th-century Jerusalem-centred Mappa Mundi suffers by comparison, sacrificing information to the urge to provide what amounted to a guide through the world’s dangers to its Christian heart. But its very constriction provides physical evidence of the terrifying pressure Islam exerted on Europe from east and west until the 15th century. In similar fashion, Mackinder’s Central Asian map reveals the deep fear of a British empire past its peak of the threat from a German-Russian alliance.

The intellectual background to these images is conveyed with beguiling erudition. Perhaps the most satisfying example is the link made between Mercator’s secrecy about the mathematical calculation that gave rise to his projection and his deeply concealed Protestant mysticism that tried to read the shape of divine intentions in the pattern of everyday appearance.

But two modern maps provide the best illustration of Brotton’s thesis. In 1974, the German cartographer Arno Peters infuriated the mapping establishment with his projection apparently showing the proper area of every landmass, and in particular the enormous size of Africa. Brotton is merciless in exposing his mistakes, but even more incisive in showing that the fury Peters aroused was both political, for diminishing the importance of the wealthy north, and professional, for giving the game away about the arbitrariness of choosing a projection.

Finally, with an elegance that typifies his book, the author links the gaze of the Google Earth satellites looking down from space to Socrates’ account of the transcendent vision that he might glimpse after death viewing the earth from above, where it would look like ‘one of those 12-piece leather balls, variegated, a patchwork of colours’. The rise of the near-immaterial Socratic soul from his body is counterpoised with the reverse journey of the Google map from 11,000 kilometres out in space as its focus closes vertiginously in on the mortal world narrowing from continents to countries to towns to houses, until the magnification makes it possible to recognise an individual’s face. Because the image is digitised, a computer-generated leap through the skin allows the mapping of ever greater detail, until no doubt a cartographer’s view will one day come to rest on the smallest possible mass within our bodies, the Higgs boson, the God particle.

There is nothing more subversive than a map.

Comments