For far too long, John Martin (1789–1854) has been dismissed as ‘Mad’ Martin, the prophet of doom. In the eyes of many, this unacademic painter was a grotesque curiosity, producing colossal pictures of apocalyptic destruction, crude dramas of catastrophe and tumult, much to the delight of the populace. The mere fact that he was so popular an image-maker made him irredeemably vulgar (rather like Lowry today), and the cognoscenti looked for faults rather than appreciating his strengths.

In fact, Martin was a reforming inventor as well as a painter, much concerned with draining the marshes around London and ensuring a pure water supply for the capital, simply because he wanted, as he says in his ‘autobiography’, to improve the condition of the people. This document, published now by the Tate as ‘Sketches of My Life’ (£4.99), is a mere seven pages but full of interest. Far from being deranged, John Martin was a typical figure of the age: self-reliant, immensely energetic, ambitious and successful. It’s high time the epithet ‘mad’ was dropped from his profile.

He trained as a decorative painter, working on glass and china, but soon recognised the potential of dramatic landscape painting. He was, first and foremost, a commercial artist, and he was shrewd enough to identify a market and exploit it, going for sensation (like any young British artist of the 1990s) and making biblical devastation and natural disaster his specialism. He was not naturally religious, though he acted the visionary with conviction; his private inclination was rationalist and scientific. Catching the public eye in 1816 with ‘Joshua commanding the Sun to stand still’, he enjoyed great success in the 1820s before suffering something of an eclipse and financial crisis towards the end of the 1830s.

His career trajectory was revealing of the man: he grew so incensed by the illegal pirating of his works in print (even though he attempted to do all his printmaking himself) that he turned to town-planning, and nearly bankrupted himself in trying to improve the common weal. Not prepared to be beaten, however, he made a calculated comeback to the art world with a crowd-pleasing ‘Coronation’ painting in 1837, and went on to paint some of his best pictures.

Martin soon gave up on the Royal Academy as a shop window, deciding it was a monopoly ruled by bigots, and sought alternative ways of reaching the public. He hired a room at the famous Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly and hung his paintings there; also at the Western Exchange, a kind of ‘high-class shopping centre’ (as the catalogue has it). Later he toured his great ‘Last Judgment’ triptych around the country, allowing it to be shown in theatres and music halls as well as galleries. It went on the road for 20 years, travelling as far as Australia and America, with an estimated audience of 8 million. In using these alternative exhibition strategies, Martin foreshadowed the YBAs of our own time, who have rented warehouses or taken over disused shops to show their work.

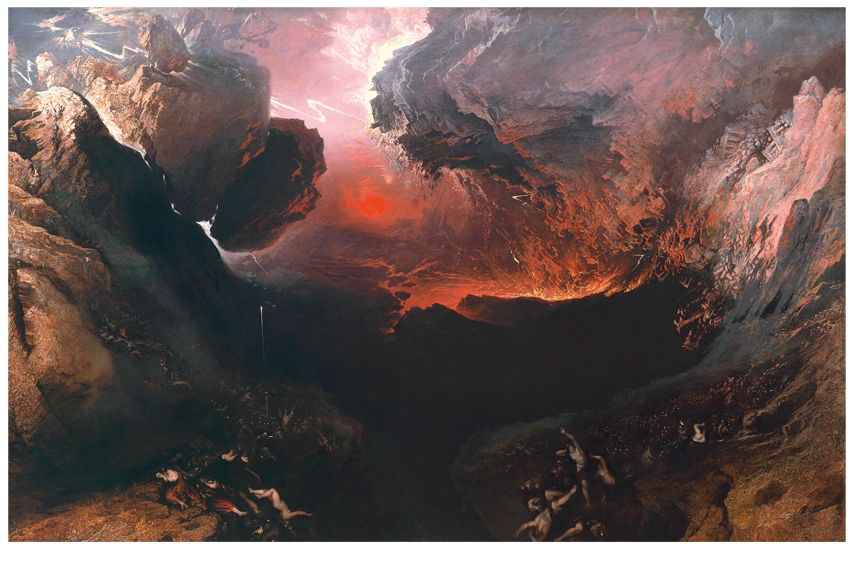

The Tate’s exhibition, as nearly every show in the Linbury Galleries, is too drawn out, though full of prodigious things. In Room 1, together with a group of small paintings including a couple of landscapes of Kensington Gardens, is the first appearance of Martin’s trademark forked lightning or zigzag thunderbolt, just visible in the background of ‘Sadak in Search of the Waters of Oblivion’. Room 2 witnesses his rise to fame with ‘Belshazzar’s Feast’ and ‘The Destruction of Pompeii’. In these grand paintings, the people are almost incidental; what rivets our attention are the sublime light effects, the overpowering architectural settings, the caves of molten rock and lava falls. Room 3 focuses on Martin’s mezzotints, the engravings that helped so much to spread his fame, and whose tonal subtleties accurately and effectively reproduced his images.

As a painter, Martin has his technical deficiencies, but the opportunity to study his surfaces here is fascinating. Look, for instance, at the remarkable scraped and scrubby canvas ‘Battle Scene’ of 1837 in Room 4. Compare the more traditionally painted ‘Celestial City and the Rivers of Bliss’ nearby, with its areas of considerable impasto in the lower sections. Occasionally, I found myself thinking of Samuel Palmer, or the scene painter de Loutherbourg, who was so good at depicting the new furnace-strewn landscape of the Industrial Revolution. Martin’s paintings didn’t all spring fully-armed from his imagination, they were formed by what he himself witnessed, from the unspoilt Tyne valley of his youth to the fire-lit industrial vistas of his maturity.

At the heart of the exhibition is a show within the show, a trio of huge paintings, the ‘Last Judgment’ triptych, hung in front of tiered seats, with a ten-minute performance every half-hour. This is a true spectacle, gimmicky but effective, the soundtrack a combination of music and emotive commentary, the lightshow an impressive display of special effects. Projection on to these vast canvases makes waves ripple and ember caverns pulse fiercely; the lecturer becomes a hellfire preacher, and thunder and earthquake shake the auditorium. Filmic effects are appropriate for paintings which prefigure the works of D.W. Griffith, De Mille and Ridley Scott. The performance is a marvellous bonus, and there’s still a room of fine late paintings before you leave. What an artist — eminently sane, I’d have said.

By way of contrast, let me recommend an exhibition of new work by Nina Murdoch (born 1970), at Marlborough Fine Art, 6 Albemarle Street, W1, until 26 November (see page 35). Murdoch paints striking scenes of illuminated darkness, superficially rather like John Martin’s. There is the same passion for large architectural effects and for the unexpected richness of natural light. Coming from the Tate, you might be forgiven for finding the same sense of menace and eschatological threat. But Murdoch is not a maker of apocalyptic narratives; in fact, she is against narrative altogether. Her paintings are composed of many layers of tempera paint, constantly reworked until the right formal equation is achieved. Their ostensible subjects are the exterior spaces between buildings, or the interior corners of shadowy chambers. Their real subject is the intense, almost mystical drama of the fall of light. Her deep blues and pearlescent golds may be less doomy than Martin’s blazing reds, but they are equally as engaging.

Comments