A few weeks ago, in a cover piece for the magazine, Rod Liddle

backed John Sentamu as the next Archbishop of Canterbury. Given that Rowan Williams announced his resignation today, here’s that article again:

Who shall be the next Archbishop of Canterbury, do you suppose? They are jockeying for position at the moment, suffused with godliness and the distinct suspicion that old beardie has had more than

enough and may wish to shuffle off to a warm university sinecure some time soon. The more cynical among you might not give a monkey’s and, indeed, suggest that jockeying for position to

inherit Rowan’s mantle is akin to jockeying within the Romanov family to inherit Nicholas II’s mantle in about 1915. As with most artefacts of western civilisation —

manufacturing, education, the armed forces, the press — the story is about managed decline. That will be the job of the next Archbishop of Canterbury, as it has been the job of the previous

three, at least: to shepherd us all, as slowly and comfortably as possible, towards oblivion.

The Church of England’s decay right now is even more marked, mind; only at the clean-cut shiny-faced guitar-toting creationist and fundamentalist margins is the Church punching at its weight, with the number of worshippers actually increasing year on year. At the high-church end there is the distinct whiff of dissolution, or even extinction. In Rome, the Pope issues the occasional laconic invitation to distressed Anglo-Catholic communicants to join the proper Church, in the manner of a top-four Premier League football team acquiring aspirant players from the likes of Barnsley or Gillingham. The Church seems confused and fragile. The problem is less that it is split on the issue of whether or not God loathes homosexuals, or just loathes what they get up to with one another, or actually quite likes them and doesn’t mind either way, than that a dispute so fantastically banal could be allowed to threaten its existence. The root of the dilemma, I would guess, is that with the leadership of the Church of England entrenched in its most bien-pensant phase it is caught in that most tricksy of bien-pensant traps: whom should we offend, the black people or the gay people? Rowan Williams, who would much prefer to annoy the black people on this particular issue, has opted for trying to keep both sides, well, if not actually happy, then less mutinous than might otherwise be the case. Then you add in the third dilemma for a bien-pensant Anglican — how to get on with good old Islam, another Premier League outfit which we might compare to Don Revie’s Leeds United team of the early 1970s — and the confusion is complete. Like all bien-pensant lefties, Rowan Williams went out of his way to accommodate Islam, going so far as to suggest that aspects of Sharia law should be tolerated in areas with a high Muslim population. He did not call for Christians to be actually executed, mind you (a course of action upon which Sharia law is, to be fair, somewhat equivocal) but his pronouncements suggested that at precisely the wrong time, the Church of England was opting for collaboration or submission rather than simply ‘interfaith dialogue’.

Islam and the C of E are opposite sides of the equation, when it comes to the vexed question of survival. Islam has survived and prospered by making as few concessions to the secular world as it possibly can, thus allowing its adherents to root themselves in a moral continuity. The Anglican Church has, until recently, survived and prospered by doing precisely the opposite. Its strength has been an ability to assimilate social change, to move with the times — which is, of course, why it was set up in the first place, if you recall. But it did so with a gradualism which is now beyond its reach; the most successful elements of the Anglican communion are those bits which hate homosexuals and aren’t terribly keen on women doing stuff; they are also, in Africa at least, the parts which are most viscerally opposed to Islam (because of course the threat to Christians in the likes of Nigeria and Sudan is rather more pressing than it is around Lambeth Palace). There are one or two African bishops who favour a — shall we say — very muscular Christian, Old Testament approach to the question of what to do about Muslims. And again, within this most civilised of countries, the strongest and most thriving parts of the Church reflect the views of the Africans, if a little more palely.

So, where should it go next? You’d get very good odds on Nolbert Kunonga, the berserk Bishop of Harare, being the next Archbishop of Canterbury. This maniacally homophobic thug was imposed upon the Church by Robert Mugabe and immediately began nicking Anglican property and having more traditional worshippers beaten up. Nolbert would certainly bring a little zest to the proceedings but sadly he is not in the running. Instead we have two prominent candidates — and regrettably, neither of them are Michael Nazir-Ali, the former Bishop of Rochester, either. He retired two years ago having looked, one assumes, ever more askance at the church’s sublimation before Islam, not to mention its fashionable metropolitan liberal bias. Nazir-Ali is a Pakistani by birth, so he knows of what he speaks when he attacks Islam for its intransigence and hostility and indeed its sense of perpetual victimhood. Further, his view that multiculturalism was ‘newfangled and insecure’ ran at odds to the views of Lambeth Palace, even if it was in accordance with the views of most people in the country. But he is gone, which is a shame. Much of his time now is spent attempting to protect persecuted Christian minorities in Islamic hellholes, a chore which has been overlooked for a long while by Lambeth Palace.

•••

This leaves us with Richard Chartres, the Bishop of London, and John Sentamu, the Archbishop of York. Both are decent men, both are — in the very broadest sense of the term — conservative, by which I mean only that they are not bien-pensant liberal. Neither is so gung-ho for sodomy as the more ‘radical’ elements of the church might like. One has an ecclesiastical beard and is much liked by the royal family — another institution where managing decline is the imperative, you might argue. The other is black and is terribly popular with the media.

Chartres was overlooked last time around, presumably for political reasons, despite having been the favourite. He is a traditionalist who nonetheless mixes well with liberals: he had a strong relationship with the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie, who on social issues was of course further to the left than a fish-fork. He is given to the occasional weirdo pronouncement, such as that it is deeply sinful to fly on an aeroplane, a statement which brought a long guffaw from the boss of Ryanair, Michael O’Leary. On the subject of homosexual priests, Chartres seems to believe that homosexuals should be welcomed into the Church but should try to refrain from buggery, if at all possible. A priest should be either celibate or living within a faithful heterosexual relationship, and further he is not terribly fond of women priests. The vote of the Queen, by the way, did not help him very much last time around.

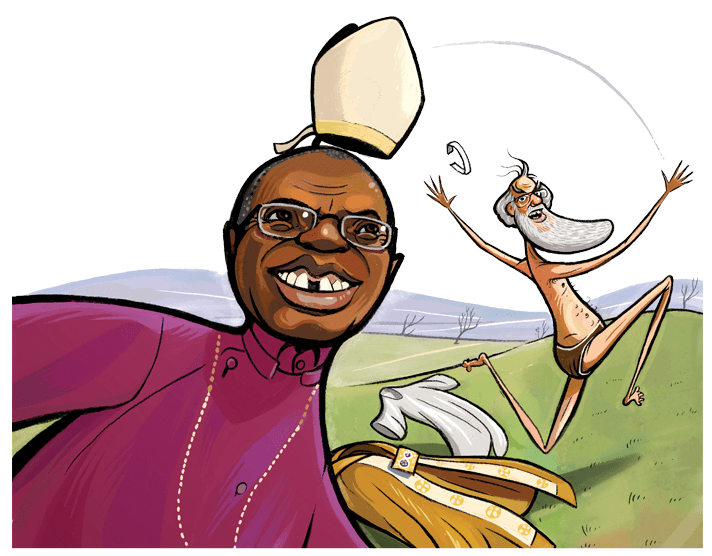

Which leaves John Tucker Mugabi Sentamu, Ugandan-born and easily our most charismatic — in the secular sense — churchman we have at the moment. For this, he is sometimes pilloried: for grandstanding, showboating and what have you. But you have to say, the Church of England could do with a little bit of charisma right now. He is outspoken; he was fantastically acute about New Labour, for example, suggesting that the government was ‘sacrificing liberty in favour of an abused form of equality — not a meaningful equality but one based upon diktat and bureaucracy which overreaches into the realm of personal conscience’. That, I think you will agree, is good stuff. Indeed, his views on the now despised creed of multiculturalism would have landed him in hot water were he not himself black. Multiculturalism was a betrayal, he argued, which led to the isolation of communities. The vast majority of people in Britain, he suggested, wished to get along peaceably enough with their neighbours, no matter from what ethnic background or religious denomination they hailed. There will always be a small tranche at the margins who will refuse to get along with anyone, ‘but you cannot use legislation to cure a minority. It will not work.’ He is not terribly keen on gay marriage, which would put him at odds with the present government, and he has been as outspoken about Islam as Michael Nazir-Ali, having on at least one occasion accused the BBC of being ‘frightened’ to criticise Islam, and on another of attacking the state-led persecution of British Christians in the workplace. As a black African himself, he may be a unifying appointment for the Church of England; as a populist his views will not alienate his British Christian congregation. He is not a ‘large C’ Conservative and may find himself at odds with the present administration. But he is the best bet for the Church, by some margin.

Comments