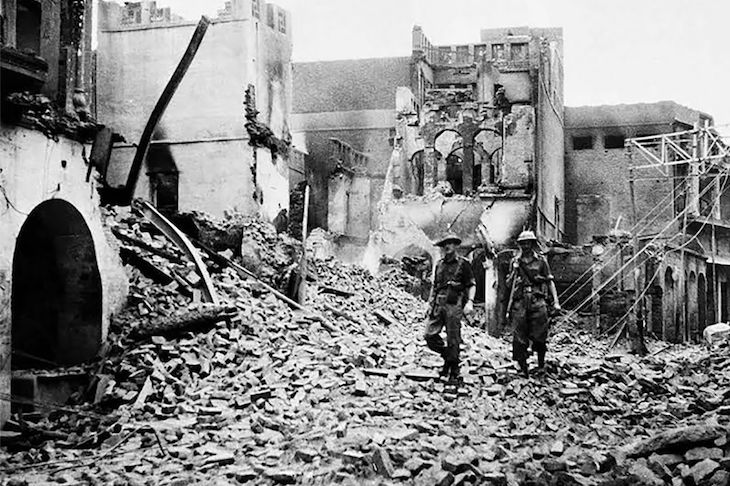

As Europe remembers Passchendaele, India and Pakistan recall Partition, just 70 years ago, when Britain so hastily abandoned its Indian empire, exhausted by the costs of war in the world and troubled by the upsurge in violence between Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs as the campaign for Britain to Quit India took root. In Partition Voices on Radio 4 (produced by Mike Gallagher, Tim Smith and Ant Adeane), we heard from those who witnessed the bloody terror that broke out across the subcontinent as it was divided on religious, not political, ethnic or communal grounds, many of whom fled to Britain to make new lives for themselves. Harun, who was a child in Delhi, remembers the smell of excrement and the sound of women crying as his family waited in a place of refuge until their safe passage out of the country could be secured. Ten million people were forced to move away from their ancestral homes and to find a new life across the artificial borders separating India and Pakistan that had been finalised by Cyril Radcliffe, a lawyer from England who had never before visited India and who was appointed in June to draw up those borders just a few weeks before the declaration of Indian independence at the stroke of midnight on 14/15 August 1947.

In the first of three programmes we also heard from Pamela, whose father worked for the Raj. She was riding on her Raleigh bike to the market in Calcutta along a busy highway when a Muslim activist pushed her off it into the swirling mayhem of cars, carts, scooters and rickshaws. ‘I could have been killed,’ she recalled. She and her mother and sister were soon sent back to Britain, never to return. Kenneth, whose family managed jute mills in the city, remembered his boyhood love of fishing in the Hooghly and that he got so used to seeing dead bodies floating by he just pushed them out of the way with his rod.

But a far more multifaceted portrait of the aftereffects of 1947 was given by Mark Tully in his programme for the World Service, Children of Partition (produced by Frank Stirling). Tully talked to young people across India to find out what the events of 1947 meant to them. In Amritsar, in the north-western Indian state of Punjab, he met the Sikh and Christian guardians of the shrine of a Muslim saint, who have looked after it since 1947, in spite of the Muslims having left because of the blood-soaked violence. ‘It belonged to everyone,’ they told Tully when he asked them why they were still doing this. ‘He [the saint] showed love to everyone.’

In Chandigarh, the capital of Punjab and a legacy of Partition because it was built up as a new city (designed by Le Corbusier) when Lahore, the original capital, was signed over to Pakistan, Tully talked to history students who told him that they had been taught what happened and when but not why or how. They wanted the horrors of Partition to be kept alive, to ensure it never happens again, but at the same time were surprisingly optimistic about the future. ‘Because of the broader connection on a global level,’ they told him, ‘we can actually talk to other people.’

Tully, though, ensured we were also given some understanding of how difficult it can be to live with the legacy of the British withdrawal by attempting to visit Kashmir. This he could not do because of an outbreak of violent protest. Instead he met Kashmiris in Delhi who told him that not a single family in Kashmir has been untouched by the violence that has followed those political decisions. In Bangladesh, meanwhile, which suffered not just from the events of 1947 but from the bloody civil war of 1971 caused by the establishment of those unrealistic frontiers, he was told, with hope, that Bangladesh is recovering. It is possible ‘to undo the damage of history’ but this depends on leadership. ‘We need leaders who have a sense of history rather than merely read it.’

Another history lesson was provided, surprisingly, by Jane Garvey’s interviews with Patricia Greene on Woman’s Hour last week. ‘Paddy’ has played Jill Archer in the Ambridge soap for 60 years since she arrived on the scene as ‘a flighty blonde’ designed to capture the heart of the grief-stricken Phil, still mourning his late wife Grace, killed off in that infamous stable fire. Garvey took Jill/Paddy, the Mary Berry of Radio 4 with her lemon-drizzle cake and home-made pork pies, through her years as young mother, stroppy farmer’s wife, mistress of the Aga, by playing clips from old editions. Back in 1957 Jill had such a posh voice she sounded as if she was having tea with the Queen (much to Paddy’s own astonishment). Two years later, though, the series was raising the difficult question of male sperm counts, the valiant Jill always ready to speak out. Yet almost a generation later, in 1982, Phil and Jill were quarrelling because she had spent the potato money as if it was her own. It was like leafing through an album of old photos: were we really like that then?

Comments