In 2006, after five decades, Shaun Greenhalgh lost his enthusiasm for the British Museum. From a very early age, he had been inspired by its contents to a profitable and diverse career in art forgery from his Bolton garden shed. A teenage talent for faking Victoriana had led him on to make an array of millennia-traversing art works, in all media, which he sold with the help of his ageing parents and which came to rest in eminent quarters both private and public.

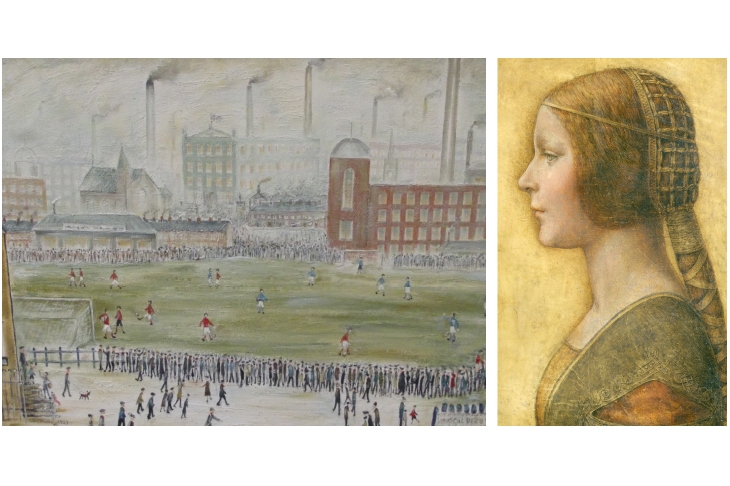

His work was taken by one American president to be that of the distinguished neoclassical sculptor Horatio Greenough. Others took him for Leonardo, Lowry, Gauguin, Moran or Hepworth. Among the few to acquire a genuine Greenhalgh was none other than Barbara Hepworth herself. She hurried away without paying for the booty under her arm: a ‘shark with a toothy grin, hanging tail up, its head resting on a lobster pot and some nets.’

For years, Greenhalgh had flown high over the heads of experts and dealers, but he came too close to the sun with the British Museum. Hitherto a happy customer, it backed away just in time from paying at least £300,000 for a supposed Assyrian relief of a priest dating from the seventh century BC.

When Scotland Yard arrived at his front door, one of the arresting officers remarked that the crammed house was ‘the northern annexe of the British Museum’; you could also see it as an off-shoot of Ealing Studios. But despite all the chicanery (redolent of Kyril Bonfiglioli’s art-dealer Mortdecai) here is riveting and affecting Northern realism: Greenhalgh’s knowledge is as daunting as it is inspiring.

Born somewhere between the end of the Chatterley ban and the Beatles’ first LP, he had little time for the era’s music. ‘My own favourite sound is the wind in full-leaf trees, something unmatched by any composer. Nature, at full stretch, always surpasses art.’ His modest family circumstances were no obstacle to his talent. When he was two or three, his father guided the pencil in his hand so that ‘a creature would appear magically before me’. He was off.

He learned on the hoof, inspired by Bolton Museum’s Egyptology department, even sneaking away from a Doctor Who movie to study the mummies (‘I got a good slapping for my trouble. I’ve rarely been to the cinema since’). Omnivorous, forever alert, he revelled in a childhood holiday in St Ives — where Hepworth acquired that shark picture when she passed by. There were other enthusiasms, including falconry and motorcycling, and, although shy, he chose geography over history, such were his adolescent hopes of the teacher in a short dress.

Formal education ended at 15, but two years earlier his garden sculptures had netted as much as a friend’s police-sergeant father made in a month. So it went on. The book is most fascinating in detailing his many techniques, which span the centuries and avoid such pitfalls as trying to age oils. Here are paper treatments and a walking stick’s antler head creating corrugation. All this supports his assertion that ‘there’s more to art than just art history. Those expert bodies probably need a few practical people on their staff’.

Perhaps best of all is a short, painful section about a girlfriend who died from a brain tumour. Had she lived, he suggests, his life might have taken an entirely different course. As it is, his story brings to mind David Bowie: ‘I’ve never caught a glimpse / of how the others must see the faker, / I’m much too fast to take that test.’ Greenhalgh’s pace matches Bowie’s, and only later does one start to reflect that the border between taking inspiration and promulgating fakery is fluid. For a chameleon, the fork in the road can bring either acclaim or, in Greenhalgh’s case, four years in jail.

Meanwhile, all those who sold on his works remained at large — even one who ensured that a piece reached the Royal Collection, for a low price (apparently no one outbids Her Majesty). But Greenhalgh himself is most startled that the ‘Greenough’ bust of Jefferson is now Bill Clinton’s property. He had made it by ageing some ‘bog-standard’ Stoke clay with squirts of Mr Sheen.

Meanwhile, whether or not that early shark picture survives in the Hepworth archive, perhaps a canny spirit could re-create it. There are many out there who would delight in claiming ‘I’ve made a killing with an early Greenhalgh!’

Comments