One of the troubles with opera is that since creating and putting one on involves so many people many composers write as if for eternity, or at least for a sizeable segment of it. It’s been a great boon in recent years that some companies, notably Tête-à-Tête, have encouraged the creation and production of operas-in-progress and of short pieces which enable composers and librettists, and the mainly young performers they recruit, to find out what they might be good at. It’s a great boost for the spirits of the opera-goer to realise that, if he is being bored rigid by a piece, there is only 20 or so minutes of it.

ROH2 at the Linbury Studio has its own interesting variation on that, Operashots, in which established figures, but not necessarily in opera, are invited to write a piece which makes no great demands on staging, but which is mounted by seasoned performers. In May there is a new opera by James MacMillan, but for the present there is a double-bill which I found immensely enjoyable.

The first piece, about 40 minutes long, is The Tell-Tale Heart, a close adaptation of the very short story by Edgar Allan Poe. The libretto and music are both by Stewart Copeland, founder and drummer of The Police and writer of many movie scores, a previous short opera and miscellaneous works in various genres. The action involves an obsessive who insists that he is sane, but needs to get rid of a neighbour, who has a troubling hypnotic blue eye. To that end, he is extremely kind to the old man, until he murders and dismembers him and puts him under the floorboards, only to be overcome by horror at the insistent noisy beating of the dead man’s heart, so that he confesses to the visiting policeman and neighbours.

It’s a vivid, fairly funny and very macabre piece, performed brilliantly. Edgar, the murderer, is played by Richard Suart, incomparable Ko-Ko of many ENO Mikados, and ideal for poker-faced lunacy. Almost all his words are audible, too, more than can be said for most of the evening’s singers. The orchestra is the chamber ensemble CHROMA, and they provide a continuous, propulsive, often scarcely noticeable commentary, much of it appropriately onomatopoeic.

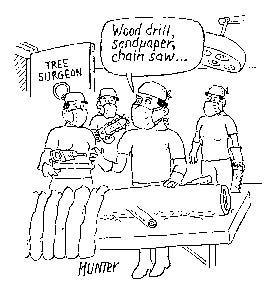

After an immense interval, most of it required for the audience to clamber out of and back into the auditorium, we had the hour-long The Doctor’s Tale. The libretto for this is by Terry Jones, director of such masterpieces as Life of Brian and Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life. Expectations were high, and partly fulfilled, though as in most of Monty Python’s extended pieces, quality control was on the relaxed side. The music, much more eclectic and varied than in The Tell-Tale Heart, is by Anne Dudley, Oscar winner for the superb music of the movie The Full Monty. The doctor of the title, also a dog, is the accomplished, versatile tenor Darren Abrahams: he sported a convincing tail but inadequately floppy ears. Anne Dudley’s note in the programme makes it clear that she and her team are much less concerned to create a coherent piece than to exploit and make fun of the preoccupations and passions which they take to be typical of the genre of opera.

One can imagine that, with enough encouragement, The Doctor’s Tale, which is at present a somewhat inchoate work, could be expanded, worked on in several ways, until it became a full-length zany entertainment, doing for opera, or some kinds of opera, what The Life of Brian did for religious epic movies. Some of what will be the highlights of the envisaged finished product are already there, such as the marvellous scene in heaven, populated of course by insufferably happy angels on Styrofoam clouds, with appropriate musical accompaniment. Dr Scout, as the slain dog-doctor is called, is eager not to stay there, and is revived so that he doesn’t have to.

There are lots of jokes involving the singing of the names of diseases, but if this work is really to take off, it needs to satirise not only the things that, it’s always said, opera is best at — Anne Dudley lists ‘love at first sight, irrational hatred, death, prejudice…’ — but also some of the idioms in which it has dealt with them, and that isn’t really achieved here, or only with so broad a brush that it doesn’t do its target sufficient damage. Still, whatever one’s reservations, it evoked more laughter than you expect to hear in an opera house, and gave a gifted small team of singers a chance to display their comic talents to the full.

Comments