This weekend, of all weekends, is a moment for reflection. The eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month will be a real thing. One hundred years on, but remembered all the more because of that. Here, as all across Europe, the centenary of Germany’s capitulation will be marked by the customary services of remembrance. The Great War was not, as it turned out, the war to end all wars but the shadows it casts are with us still.

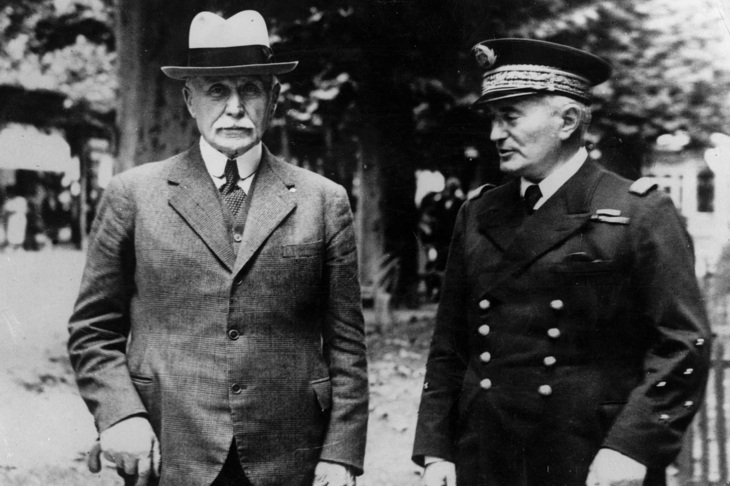

And in France there is fresh “controversy”. President Emmanuel Macron announced he would honour Marshal Philippe Petain for his part in the saving of France. The Marshal was not the only man to do this but he was the pre-eminent hero nonetheless. That was 1918, however, and what came later is a different, and complicating, thing.

Bluntly, is it possible to separate the Petain of 1918 from the Petain of 1940? That seems the wrong question or, rather, the wrong set of dates. Can the Petain of 1940 be distinguished from the Petain of 1943, 1944 and 1945?

The great advantage of Britain’s second world war story is that it is, for the most part, simple. France’s story is rather different just as the stories of so many other continental countries are so very far removed from, and so much more ambiguous than, our own. Our WW2 story is easy even if it is sometimes over-simplified. We stood alone, briefly, and even if we were not quite as alone as we like to recall we were alone enough for it to matter and be important and make the difference. We bought time.

Elsewhere, however, accommodations had to be made and we delude ourselves if we think such arrangements would not have been required here if circumstances had been different. The people of the Channel Islands did their best to muddle through their occupation but there were, if we are being honest here, few profiles in courage there. Fate was a bloody bugger and you did what you had to do to get by. There were times and places for reckless heroism and futile gestures and other times and places when these were not uppermost priorities.

So it was in France and elsewhere too. If mighty France could fall – albeit at the cost of 100,000 casualties – surely Britain would fall too? And who, in any case, was this de Gaulle? A man of whom almost no-one had heard and who commanded precious little faith even amongst those who had. In those circumstances, dire beyond description, the idea of salvaging whatever could be saved from the wreckage of defeat was neither necessarily absurd nor dishonourable. This was not the world these Frenchmen wished to live in; it was the reality they had to accommodate.

We so often forget how lucky our war was. If it was often miserable it was never nearly so agonising as the war endured by our continental friends. Britain’s role was to buy time. Victory, all those years later, was facilitated by Britain but delivered by the Soviets and the Americans. There is nothing diminishing about this; the finest hour was a real thing even if it is also something that demands perspective. Anthony Eden was right: when he was asked about our war and France’s war, he said it was not the place of anyone from a country that had not been occupied to pass withering judgement on the people of any country that had been.

Again, our war was easier. In 1940 Vichy was engaged in the business of making the best of an impossible lot. Could something of France be saved from the shipwreck? It made sense that Petain, the old man who had saved an idea of France once before, should be charged with rescuing something from the horrors of 1940. A number of novelists, including Piers Paul Read and some others rather closer to home, have explored this compelling question: could a French patriot serve Vichy as an honourable man?

The answer, as the question was asked in 1940, seems to me to be Yes. At that moment, in that place, this could plausibly appear the least terrible of all the dreadful possibilities available. Not good, but not as bad as complete capitulation or complete occupation.

Collaboration imposes its own taxes however, and they are levied at increasingly punitive rates. What might have been true, or at least plausible, in 1940 was no longer either true or plausible three years later. Evil demands accessories and that slide into willing acquiescence became both inescapable and doubly shameful. By then the idea of preserving some notion of France became a fantasy and something worse than that too: a wicked and cynical betrayal. By then, the gap between surviving and aiding became so thin the two became indistinguishable. A corruption, not a means of salvage.

The French, post-war, recognised as much while also acknowledging the complexities of the situation. Petain was tried for treason and convicted but his death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. There were reasons for this beyond his own antiquity but that verdict implicitly recognised both the ambiguity of France’s war and the necessity to try and draw some line beneath it even as a just and vital verdict was reached.

Our war, again, was blissfully simple. After America, we were the luckiest party to the conflict. Look to the east, for instance. Think of the Indian Legion, led by Sundhas Chandra Bose, that fought with the Nazis in the belief that defeating Britain would hasten India’s independence. Think too of those Estonian and Latvian and Lithuanian and Ukrainian forces that fought with Germany against the Soviet Union in the belief that Nazism was, for them, a less pressing evil than Soviet occupation. Many of those units operated with a brutality that shocked even their German allies. They were mistaken and wrong but we can also recognise they operated in an environment in which, in general terms, there were no happy or honest or good options. Sometimes making a deal with the devil can seem the best deal there is.

That is no kind of happy thing. But our understanding, or memory, of these wars is both imperfect and predicated upon what is, in the end, a happy accident of geography. Our island status saved us in 1940; our willingness to render judgment on peoples who were not so fortuitously protected by geography does us little credit.

As for the Great War, well there again even as we suffered appallingly we suffered less than peoples elsewhere. Germany had it much worse and so did France and not just because much of the fighting took place on French soil. The Somme was terrible but it was not Verdun. And because the Great War, horrific as it was, did not scar our land so we forget or minimise its impact upon the French in particular.

Petain helped save France in 1916 and 1917. That is, he helped allow for the possibility of the survival of an idea of France; the same task Charles de Gaulle took upon himself in 1940. To deny that is to deny reality and demanding that Petain be written out of France’s WW1 story because of what happened 25 years later is, in a way, to smooth history to the point at which it becomes a pointless fraud.

Saluting the Old Marshal’s first world war service can easily enough be separated from his second world war record. He saved a French army that was on the brink of collapse and that was no small thing at all. That being so it was natural, or at least understandable, that France looked to the old man in 1940 too. Collaboration is insidious, but it was also the kind of cancer that in many cases moved slowly. But while history is sometimes the business of settling old scores it is also, at other moments, a time for acknowledging the nuances of a nation’s story. It must, if truth means anything, be possible for France to commemorate the Petain of 1918 without endorsing the Petain of 1940 or, especially, the Petain of later years.

All of which is to say, again, that agonising and costly as this country’s 20th century wars were, we were so very much fortunate than peoples elsewhere. There are things to be proud of here, but also many things that demand a certain modesty. That is something to be remembered too.

Comments