A new exhibition of paintings and drawings by Leon Kossoff (born 1926) is an event in the art world. Kossoff is an intensely private man and keeps such a low profile that many people react with surprise to the information that he is still very much alive and working. Not for him the carefully calculated public appearance or widely disseminated views; he is reluctant to give interviews and finds it increasingly difficult to say anything at all about his pictures. In fact, he is so reticent about his art, and so much wants it to speak for itself, that he has discouraged several people from writing books about him. To date, there are a number of Kossoff exhibition catalogues, with more or less revealing texts, but no heavyweight monograph. For an artist of his international stature, this is remarkable.

Kossoff’s work is increasingly celebrated in America, and his current exhibition, after its London run, will travel first to New York (Mitchell-Innes & Nash, 534 West 26th Street, NY 10001, 5 May to 18 June 2011) and then to California (LA Louver, 45 North Venice Boulevard, Venice, CA 90291, 8 September to 8 October 2011). In recent years he has had museum shows in America, Australia and Switzerland, and in 2007 there was an exhibition of his drawings from the Old Masters at the National Gallery in London. His paintings are achieving higher and higher prices at auction and, after years of relative obscurity, Kossoff’s work is finally beginning to receive the attention it deserves.

In order to write about this exhibition before it opened, a special preview was arranged for me at Annely Juda Fine Art, Kossoff’s dealers for the past decade. I had hoped to interview the artist about his new work, but he politely insisted that I refrain from taping our conversation. I’m used to this — Kossoff’s contemporary, Jeffery Camp, also forbade the machine. I rather admire this mistrust of the packaging of soundbites, though this is something I’ve also striven to avoid in more than 20 years of interviewing artists, preferring a presentation that catches the flavour of an individual without processing them. With Kossoff, though, I have an additional restriction: he doesn’t want anything he says to be quoted. As far as he’s concerned, I should concentrate on writing about my own responses to his work.

Fair enough, but the artist makes the work, and a few observations are surely in order here. A small, slight man, dressed in black, clean-shaven and with a tendency to melancholy, Kossoff doesn’t look his 84 years, and shifts heavy paintings around like a much younger person. He’s not exactly lugubrious, but you sense that he is appalled by the challenge of communication, and that desperation is never far away.

It’s clear that life does not rest lightly on this man. Anxiety pursues him, the business of painting is an all-encompassing struggle which makes a contented existence impossible; but, on the other hand, not to paint is worse. He draws or paints most days, and regards painting as a form of drawing, an extension of it, as it were. Kossoff paints the same subjects: a few trusted and familiar sitters and a series of urban landscapes that have shed new light on the city in which he lives. He is a Londoner born and bred, the son of a Russian–Jewish immigrant baker, growing up in Shoreditch where one of the neighbourhood landmarks was Christchurch, Spitalfields, Hawksmoor’s famous masterpiece, massive and dominating as an Egyptian temple. Kossoff began painting its magnificent façade in the late 1980s, and three paintings of it are included here. Other subjects have ranged from a children’s swimming-pool to Kilburn Underground Station and the flower and fruit stall at Embankment Station.

People hurry through his cityscapes, but in the figure paintings they are arrested, held up for our scrutiny. Kossoff refers to the paintings of people as ‘heads’ rather than ‘portraits’, and there is something distilled and essential about their construction which suggests more of a type than an individual. His latest heads look like ancient and abraded frescoes of matriarchs or priests — wise, modest, all-seeing, ascetic. There is a hieratic quality to their depiction, a certain fierceness and lack of compromise, yet for people who know who the sitters are (his wife Peggy and the painter John Lessore are favourite models), likeness also emerges from the pared-back forms.

Kossoff agrees with Euan Uglow’s definition of a painting being ‘a state of emergency’. He makes many drawings of a subject before he feels sufficiently familiar with it to attempt a painting, after which the actual painting may take months — or years — to emerge. Kossoff’s practice is to paint and scrape off, paint and scrape off, until something tells him to leave the image. A morning’s work might be left overnight, but then ruthlessly scraped back to the bare board, leaving just a ghost of what was painted, before he starts again. It’s a kind of Sisyphean process of seemingly endless endeavour, lightened by moments of recognition, when the artist accepts that he has achieved something passable. Doubt is his constant companion, and disbelief in his abilities. Yet somehow, after Herculean exertion, he still manages to produce memorable and surprisingly positive images that look the reverse of laboured.

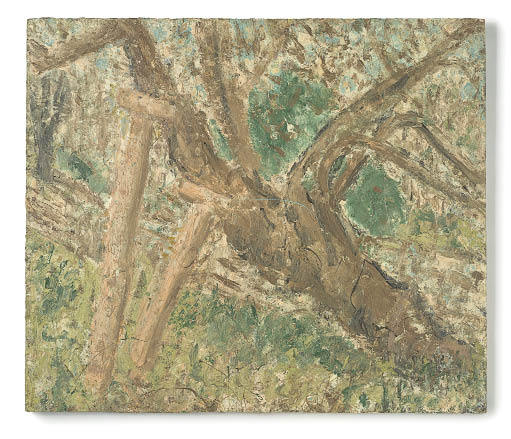

There are only 27 items in his new show, and five of these are charcoal drawings. All the drawings are studies of a particular branch of a cherry tree in his garden in Willesden, which has been propped up in an attempt to prolong its life. The drawings have led on to a series of nine paintings made between 2002 and 2008 which are marvellously varied evocations of age and infirmity, as witnessed in a London garden. The stakes that support the tree resemble pit-props in a mine shaft or crutches a person might use, and the literal image undoubtedly has a wider allegorical resonance. One of the finest paintings is the very first one Kossoff made, ‘Cherry Tree, Autumn 2002’, an amazing reconciliation of surface and depth, design and description. My other favourite is the last in the series ‘Cherry Tree, and Tube Train 2007–8’, a beautiful green painting that breathes tenderness and resolve.

Kossoff is famed for his thick surfaces, for making images from heavy deposits of paint layered on to boards. These days he paints more thinly, but the worked and reworked paintings nevertheless give the impression of a substantial impasto build-up. Over this body of paint, the main substance of the image, is another layer, a linear tracery of drips and runs of paint, which have fallen from the loaded brush in its urgent dash to get down a telling mark. This arbitrary-seeming pattern is more obvious in some paintings than in others — it is particularly noticeable and beautiful, as it sets up a poignant counterpoint with the weightier marks, in ‘Christchurch, Spitalfields, 1999–2000’. The whipping lines of these paint trickles are reminiscent of the dancing rhythms in Kossoff’s etchings (he is a prolific and inventive printmaker) and are as essential a part of the finished painting as any other mark.

The cherry-tree paintings could be seen as a celebration of the dynamics of the diagonal, with vectored energies shooting off at all angles through these powerful compositions. But for all their formal toughness, these are marvellously lyrical, even gentle, paintings, luminous and fluid, not betraying any of the hesitancy of their lengthy gestation. This is the end of this particular motif: the cherry’s branch finally had to be removed or the tree would die. Thankfully, it has recovered and was blooming again this year, but it has lost its appeal for Kossoff. He must turn his attention to other subjects.

Comments