T he historic graffiti at Eton College, chiselled into its stone walls, wooden panelling and ancient oak desks, serves as a reminder to any Etonian that he’s merely the latest in a long line of boys stretching back to 1440 who have passed through the school and occasionally bent the rules. Two names chiselled together into a wall of the Cloisters are ‘H. COLERIDGE’ and ‘E. COLERIDGE’.

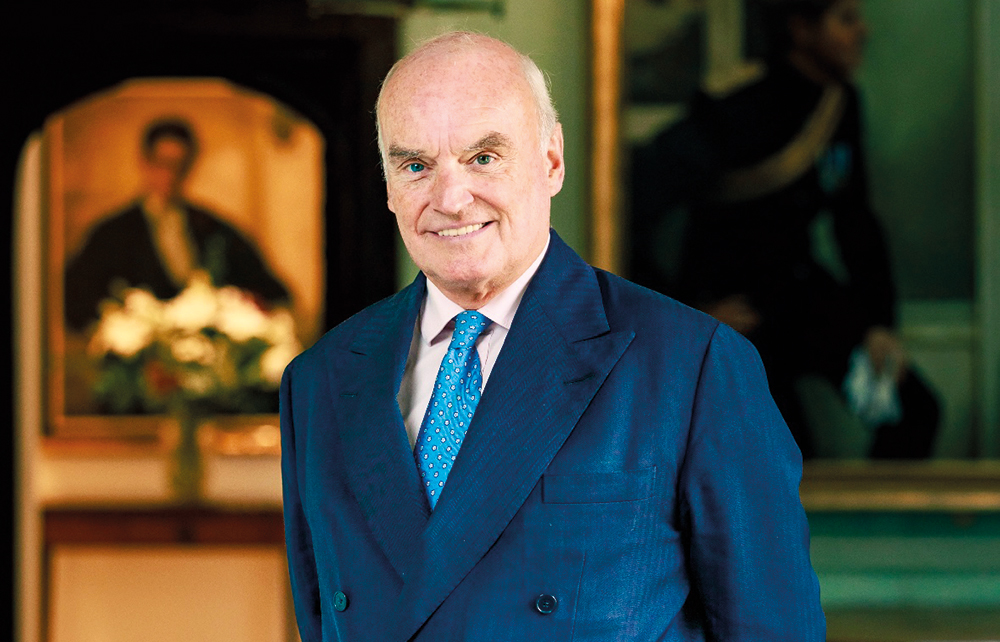

‘Not me!’ says Sir Nicholas Coleridge, Eton’s 43rd Provost, when I visit him on the last day of the summer term, ‘or any of my sons. They’re dated 1817, luckily, so we can’t be blamed.’

‘The imposition of VAT has been a very damaging thing for education. It’s pernicious’

On being given his initial tour of the 15th-century Provost’s Lodging last year by Caroline Waldegrave, wife of his predecessor, Lord Waldegrave, Coleridge experienced that same sensation – of being merely the latest in a long line. ‘Caroline took us up to a little-visited bathroom on the top floor, and said, “Oh look! That’s Martin Charteris’s bathmat! I’ve been meaning to throw it away for the last 15 years but never got round to it.”’ (Charteris was the 39th Provost, starting in 1978.)

The day of my visit happened to be the last day of Coleridge’s first year in the job. He and his wife, Georgia, were about to vacate their temporary accommodation, the Vice-Provost’s Lodging, and move into the Provost’s Lodging which has been refurbished. ‘It was last rewired in 1950 and last replumbed in 1870. Things have been accumulating in its rooms since 1440. It’s a labyrinthine house of great beauty. We feel extremely lucky.’

You really would want Coleridge as the figurehead of your institution. Fizzing with positivity and enjoyment, he’s an enhancer of success at any institution he chairs, as well as promoter of its profile, raiser of its funds and guardian of its soul. Condé Nast International (of which he was president) and the V&A (of which he was chairman) basked in the Coleridge effect, and he’s still chair of Historic Royal Palaces. Now – having been shortlisted, interviewed seven times, selected and endorsed with signatures of the Prime Minister and the King – he’s bringing his chairman’s gifts to his alma mater.

The Provost’s role is ‘Executive Chairman’, Coleridge explains, and Chairman of the Governors (‘the Fellows’) – but unlike most chairmen of governors, ‘who might visit a school 15 times a year’, Eton’s Provost is expected to live on site full-time during term-time, which he’s more than happy to do: ‘I find it incredibly inspiring and energising to be surrounded by young people.’

What does the job involve? ‘A great many meetings, on a huge variety of things. One minute we’re talking about the heritage collections here, then it’s finance meetings, audit committee meetings and board meetings. I have weekly meetings with the headmaster and the Vice Provost, and the Deputy Headmaster. We meet in a beautiful room, the Election Chamber.’

In a gown? ‘Yes! That was one of the things that took a bit of getting used to: what to wear for different occasions. I have a crib sheet. A surplice in chapel on Saints Days and Foundation days. Sometimes a gown on its own, sometimes a gown with hood, and sometimes a surplice with hood. There’s a great deal of processing in and out of halls and chapel.’

I asked him for three examples of how the school has changed since he was here in the first half of the 1970s. ‘Physically it’s almost identical,’ he says. ‘There are the same 25 boarding houses, but each one is in better condition. There’s the most extraordinarily luxurious indoor pool that in no way resembles the unheated outdoor pool where my contemporaries and I passed our swimming tests. The school is much more international than it was in my day, when I think there were two maharajahs, one African boy (a great friend of mine) and 24 from Scotland who got special leave to go up the previous evening at half-term. Out of the 1,350 pupils we have today, 325 have overseas addresses, of which the USA is the largest contingent, followed by China, India, Africa, France, Italy and Germany. The international mix reflects the working world these boys are going to be going into.

‘Another thing: in my day, you could learn Latin, Greek and French. Now you have a choice of 12 languages. You can do computer sciences – a very popular subject. Georgia and I have sat in on some divisions [lessons], and we’ve loved it. We’ve sat in on history, computer sciences, history of art… Georgia wants to sit in on a maths lesson, but I’m a bit nervous, as the last time I was in a maths lesson at this school was when I was 15 and about to do my maths O-level. Although I can read a balance sheet.’

The place is utterly seductive. Coleridge says: ‘The beauty of the architecture seeps into your soul.’ Any parent of a bright 11-year-old would long for him to go to such a school. The standard of music is ‘so high that you could be sitting in Carnegie Hall’, Coleridge says. ‘We currently have a superb pianist, Ryan Wang, who won the BBC Young Musician award last year. The school choir is superb. I go to chapel four times a week, sometimes five. And the plays! In a typical 12-week term, Georgia and I go to about 14 plays. The school play this year was The Revenger’s Tragedy. I’ve paid good money at the Almeida to see no better.’

Yes, but – how can any normal, middle-class parent afford the fees, which have risen to £63,000 a year since the imposition of VAT? ‘The first thing I’m going to say,’ he says, ‘is that the imposition of VAT has been a very damaging thing for education. We’re the only country in the entire world that taxes education. It’s pernicious. There’s no upside to it whatsoever. It has already driven 11,000 children whose parents used to pay for their education into the state sector and no plans have been made for that, of any kind. What are we doing? Well, we’ve been pleased to help 100 parents with the VAT. The Board of Fellows here felt instinctively that if a boy was already in the school, it would be the most awful thing if this new tax on learning meant that he had to leave.’ But he admits they can’t carry on helping in this way for ever.

Three hundred boys, he tells me, are on some kind of bursary, ranging from ‘partial’ to ‘110 per cent’, i.e. covering uniform and extras. ‘Eton has more bursaries than any other school of its kind in the country.’

Is there any chance of a bursary for families from the ‘squeezed middle’? ‘Eton does have a few bursaries,’ Coleridge replies, ‘endowed by generous alumni, for the “squeezed middle” as they’re sometimes called. They’re means-tested, but intended mostly for Old Etonian families who can pay part of the fees but not all, and need a top-up. I wish we had more of these.’

How has the social engineering by Oxbridge colleges, virtue-signalling as they hike their state-school quotas, affected Eton, I ask. (Oxbridge entrances from Eton halved from 99 in 2014 to 51 in 2024.) ‘Social engineering happens everywhere you look these days,’ Coleridge replies. ‘But Eton has 60 boys going to Oxbridge this year – the highest for five years. And there are 40 going to American universities. Yale, Harvard, Princeton, Brown, some on scholarships… let’s hope President Trump lets them in. He’ll be staying up the road soon.’ (Coleridge points towards Windsor Castle beyond the trees.)

‘There are 40 boys going to American universities… let’s hope President Trump lets them in’

I mention an essay by Julian Barnes, published earlier this year, in which the author lists the banning measures he’d take if he ran what he calls ‘The Benign Republic of Barnes’. They include ‘a 50-year ban on any Old Etonian becoming prime minister, and a 25-year ban on one becoming a cabinet minister’. How does Coleridge deal with that instinctive, post-Boris Johnson anti-Etonian feeling? ‘You know, Eton has to live with that stereotype. And I don’t think there’s anything that anyone can say or do that’s going to change that. Obviously not every single OE is arrogance-free, but I speak as I find. And I think most Etonian stereotypes are way wide of the mark. Since I’ve been here, I can say completely honestly that I have not seen a trace of arrogance from any boy. The characteristics of an Etonian, as I see it, are: friendly, chatty, well-informed, good-mannered, independent-minded and fun. Eton boys are usually quite confident, which is emphatically not the same as being show-offy.’

How often is he asked whether Eton plans to take girls? ‘All the time,’ he says. ‘And no human soul has ever dared to ask the headmistress of an all-girls school when she’s going to start taking boys. My answer is: never say never. We have two or three boys applying for every place here, so I can’t see the need for it yet. But we’ll see how it pans out in the future.’

After our chat, and a delicious summer lunch prepared by Georgia in the kitchen, Coleridge dashes up to London to visit a possible generous donor to the college; and his visit is entirely successful.

Comments