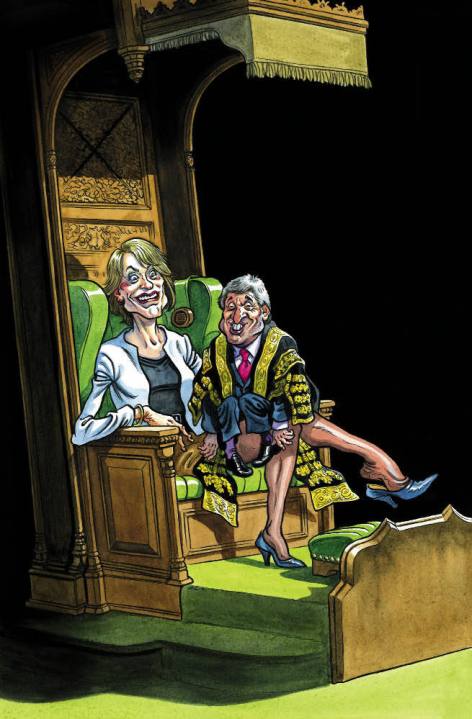

A mad, muscular Sally Bercow cavorts on the Commons chair, diminutive husband on her knee, his features impish. With a few scratches of the nib, the Independent’s merciless Dan Brown, in his cover design for this biography, passes judgment more viciously than Bobby Friedman manages over the next 250 often unexciting pages. The book is not entirely without merit. It is earnest in the manner of a schoolgirl’s essay. There are not too many spelling mistakes. The author has plainly made scores of telephone calls to old acquaintances of the man we must now, revoltingly, call Mr Speaker. Friedman deserves a B-plus for effort.

His book is not, however, as vivid as it should have been, given the preening, sycophantic, short-tempered grotesque it has for a subject. One also hoped for more humour. Bercow is a figure ripe for mockery, as Brown’s cartoon shows.

It begins with some only mildly interesting stuff about John Bercow’s Romanian grandfather, a Jewish furrier who fled to the East End of London. Friedman points out that Bercow has used his ancestry to personal advantage at times, telling the Board of Deputies of British Jews in 2010 that his father taught him to be proud of his Jewish heritage and to ‘stand up for what I am … and not to seek to hide it’. At other times, however, the same John Bercow has been distinctly reticent on the subject. Is that because Britain has been anti-Jewish and Bercow was legitimately worried? Or is it because this man has long been as slippery as an avocado stone?

Bercow’s drift from Monday Club right to Harmanesque left — a voyage which won him enough Labour votes to seize the Speakership in 2009 — is well known. Friedman is good on the rightwingery, describing in detail the manoeuvres which brought the spotty young Bercow to the leadership of the Federation of Conservative Students in the 1980s. What a frowsty spectacle they presented, sending a get-well card to General Pinochet after an assassination attempt. Some of them wore ‘Hang Nelson Mandela’ T-shirts. Friedman panics. He writes that ‘Bercow never wore one of these shirts or believed in the sentiments expressed’. How can he be so sure? It might have been better to write that ‘Bercow claims never to have worn one’. This is but a small example of the book’s credulous approach, also evident in numerous tributes to Bercow which feel like little more than padding.

We keep being told what an ‘outsider’ Bercow is and how hard it was for him to have been state-educated. Hang on. He was a university politician. He worked as a lobbyist, banker and Whitehall special adviser before landing a safe Tory seat. An outsider?

As I trundled through the book I sensed that Friedman had started with a benevolent view of Bercow, only to realise, slowly, what a horror he had uncovered. He records the various close shaves and the rackety nature of Bercow’s career with application. What the book quite fails to examine, however, is the expectations we have of a Speaker. It is also lamentably incurious about Bercow’s habits. Here is a life with, so far as the book tells us, little hinterland save for the high-class tennis of his early teens and the later arrival of children. We learn nothing about the books Bercow reads. We gain no sense of his tastes, his phobias (other than of bees), where he holidays, what he drives, how he dresses in his spare time, what his houses have looked like, what makes him laugh, what music he enjoys. A good biography does these things. Is there any religion in his life save the worship of self? My copy of Who’s Who reports that he likes films. What sort? And what are his core political beliefs? After reading this book I still don’t really know.

Comments