Soap bombshells are nothing new, but the land of light TV entertainment was rocked by some real-life drama this week: ITV announced that Coronation Street and Emmerdale will be cutting back on episodes permanently next year. It was also revealed that viewing figures for EastEnders have plummeted from 30 million at its 1980s peak, to just four million. As one of those lost viewers, I’m not surprised.

The storylines are becoming ever more unrealistic, undermining the realism that is supposed to be at the heart of the genre

I gave up watching soaps decades ago because the challenges of real-life adulthood made me less keen to soak up the fictional woes of others. But there was a time when I was hooked. I should have known my soap obsession was out of control when, during a family holiday in Greece in 1986, I hunted down a phone box to call friends and discover the outcome of that week’s big soap reveal: who had raped Brookside’s Sheila Grant? I then spent the rest of the trip shaking my head in disbelief that the taxi driver was the culprit. This was strange behaviour on a holiday, but in my defence I was only 12.

I watched soaps religiously as an adolescent. Most evenings, I’d be waiting in front of the TV long before each episode started and then I’d watch them again when they ran omnibus editions at the weekends. I’d pull a sickie off school to find out what happened in Neighbours, which was only shown at lunchtime at first, and I stayed up late at night to watch Prisoner: Cell Block H. Soap characters were my friends and family, and the theme tunes were a big part of the soundtrack of my teens.

But then I grew up. I recently started re-watching 1980s episodes of Brookside and EastEnders on streaming apps. I hoped it would be a heart-warming, nostalgic trip down memory lane, fondly revisiting the storylines and characters of my youth. Yet I was actually shocked by all the violence, despondency and abuse. As I re-watched the programmes of yesteryear, the unremitting negativity of their storylines left me feeling sad and jittery. If re-watching them made me feel that unsettled and hopeless, I can only wonder what they did to the childhood me who watched them the first time around at such an suggestible age.

By all accounts, soaps are just as gloomy now. Andrew Billen of the Times recently returned to watching them, and he found he was “struck by their homogeneity, especially their reliance on violence”. Infidelity was “rife”, there was “drug abuse” and “no public gathering proceeded peaceably”. In the end, the various plots “merged into a mush of grim, formulaic or fantastical unpleasantness”.

When I watched soaps as a kid, there were two episodes every week, but now a lot of them are on four or five times. As TV bosses panic over how they can hold onto viewers in the digital age, scripts are being churned out, actors are under more pressure and the storylines are becoming ever more unrealistic, undermining the realism that is supposed to be at the heart of the genre.

In some ways, I’m glad I watched so many soaps as a kid. There’s no doubt that following the misfortunes of working-class communities in London, Liverpool and Manchester from my position of relative privilege in leafy Putney will have made me more socially aware and the depiction of women can only have made me more empathic as a man.

Television can depict the darker sides of life brilliantly in dramas like Cathy Come Home, about homelessness, and Threads, which tackled nuclear war. More recent dramas like I, Daniel Blake have also been important works. Although Mr Bates vs The Post Office isn’t fictional, it was a reminder of the positive contribution that considered gritty broadcasting offers.

But the unremitting pace of soaps these days means they don’t have a hope of tackling the darkness artfully or sincerely. It’s almost inevitable that they’ll simply bombard viewers with shallow takes on a checklist of social issues, often acted out less than brilliantly.

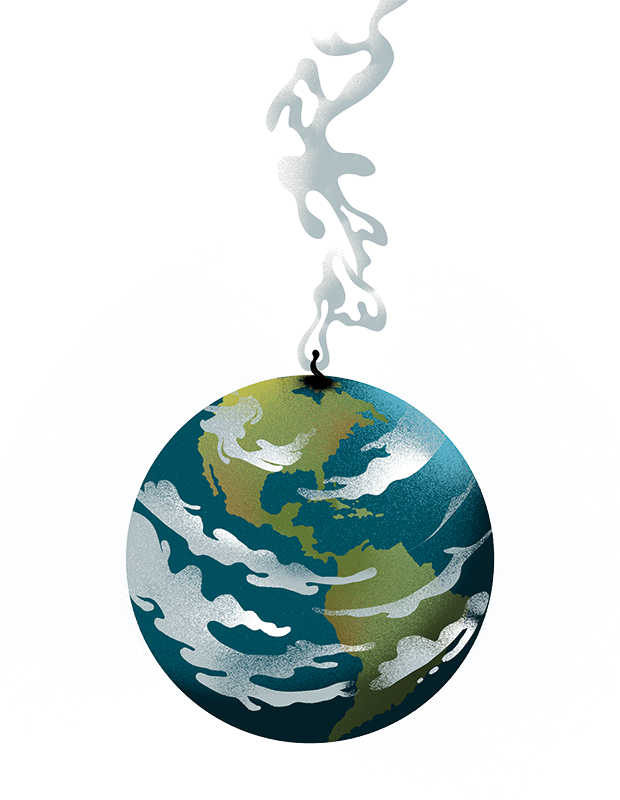

Times are gritty and unsettling enough in the real world right now, so I wonder if we still need night after night of gloom on our screens. Perhaps the collapsing viewing figures give us the answer.

Comments