Not only Webster but most of us are much possessed by death. Even if we don’t see the skull beneath the skin, we enjoy the thought that it’s there and look forward to the day when it will turn to dust so that we can sing its bygone glories.

Notoriously, the ancient Anglo-Saxons allowed their Roman buildings to fall into ruin and then wrote elegies to mourn their passing. The rise of Greek cities left the countryside to languish outside its walls and gave birth to bucolic poetry. Trains and planes proclaimed the end of parochialism and allowed for the rebirth of patriotism.

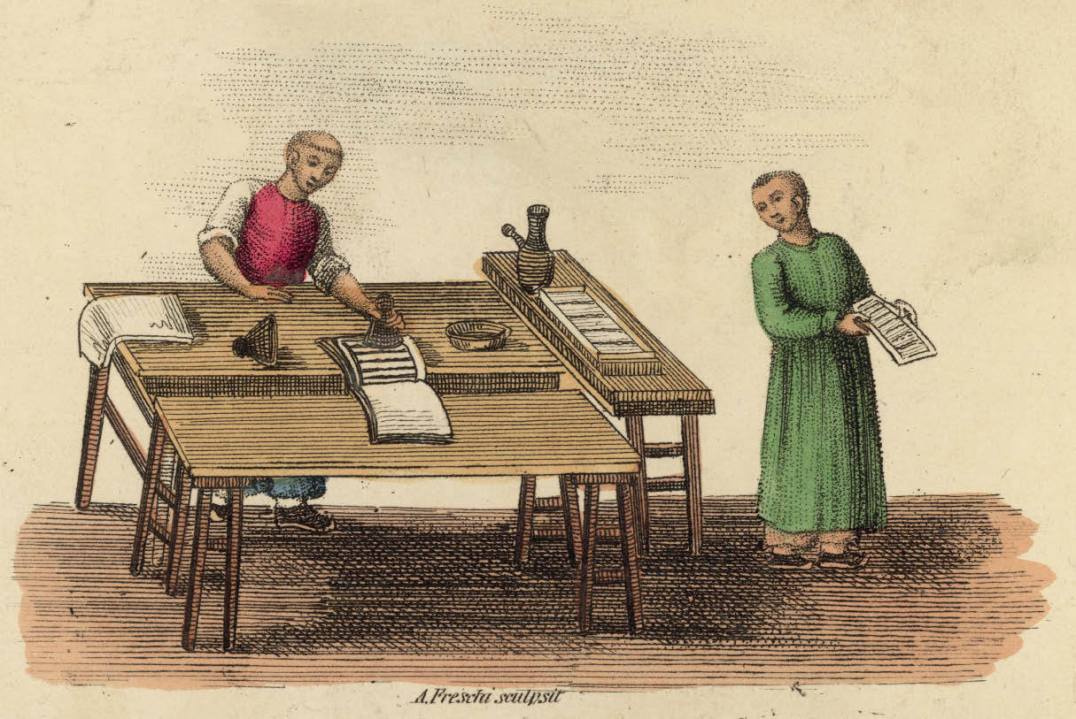

Likewise with new technologies. Photography proclaimed the death of painting, before the birth of Picasso and Jackson Pollock. Cinema announced that theatre was a thing of the past, though Brecht and Beckett were still to come. And when Gutenberg’s printing press decreed the end of the manuscript book, there sprung up a sudden passion for calligraphy, and calligraphy handbooks became early 16th-century bestsellers. Our death wishes are highly suspect.

It is therefore hardly surprising that in this age of the electronic text, which repeatedly proclaims the death of the printed book, there should be an outpouring of books on its courageous survival, on the role of the persistent reader and on our recalcitrant libraries. Bookworms appear to be crawling out from under every electronic gadget, and not a day goes by without someone, somewhere, announcing to a less than surprised world that the printed word’s pulse is still beating. Even Bill Gates, virtuality’s virtuoso, brought out his apocalyptic book on the end of paper on paper, a gesture which seemed to lack the strength of its proclaimed convictions. Now two huge compendiums have been added to the flood. One is a splendid and erudite achievement, ambitiously conceived and intelligently executed. The other is neither.

The Oxford Companion to the Book is split in two sections. The first (occupying two-thirds of Volume I) consists of essays on various aspects of the book and its history: writing systems and theories of text, editorial theory and textual criticism, the book as symbol, children’s books, etc. as well as over 30 essays on the history of the book divided geographically and ranging from Britain to sub-Saharan Africa. The second section (the last third of Volume I and the whole of Volume II) is an encyclopedia of subjects related to the book and to reading, for the most part concise and comprehensive, and thoroughly up-to-date.

In their introduction, the editors quote Dr Johnson: ‘A large work is difficult because it is large.’ Undaunted, they seem to have surmounted much of this difficulty by judiciously choosing what may be useful to both a scholar and an amateur. The scholar might be interested in comparing the problems of punctuation (or lack of it) in Greek texts of the sixth century BC to those of printed Muslim texts in the 19th century AD, as outlined in the corresponding essays on the history of the book; the amateur may want to read the brief notice given under Punctuation in the alphabetical section.

Though the notion that a book is companionable is at least as old as the Epic of Gilgamesh when, the poet tells us, ‘the king carved, for the sake of comfort, his trials on stone tablets’, the word ‘Companion’, the editors note,

does not appear as a substantive part of an English printed book title until 1576 and does not figure more than sporadically until the 17th century.

After that there are companions for everything under the sun and

among this profusion, the title that the OCB might most reasonably aspire to is A Thousand Notable Things: or, A Useful Companion for All People (London, 1701). Of course, the value of any companion depends upon one’s preference in friends.

Indeed.

For those who prefer their friends to be readers, the OCB offers a wealth of delights and a few disappointments. The delights are too many to mention; among the disappointments for this particular reader, is the fact that there is nothing but a stark scattering of bibliographical references to Jorge Luis Borges who surely redefined our relationship to the written word in texts such as The Library of Babel and Pierre Menard, Author of Don Quixote. Nor is there anything concerning two fundamental publishing ventures of the Sixties, in South America and Canada respectively: EUDEBA, the University Press of Buenos Aires, that brought affordable literary and scientific works to the general public by setting up book kiosks in streets and schools (a project dismantled by the military dictatorship) and Coach House Press in Toronto that published for the first time many of today’s best-known Canadian authors. Perhaps a future edition (and I hope there will be many) will remember these worthies.

The Cultural History of Reading is not what it proclaims to be. Like the OCB, it consists of two volumes, but there the similarities end. The editors have seen fit to divide their subject into two areas of equal importance: ‘World Literature’ occupies the first volume, ‘American Literature’ the second. One could argue that the combined literatures of Canada, Central and South America, Europe (including Great Britain), Asia, the Pacific, Africa and the Middle East, spanning over 5,000 years, carry perhaps a little more weight, universally speaking, than the two centuries of certainly important literature of the United States. But that is not the main problem of this ‘cultural history’.

Though the first line of the editors’ preface announces that their book ‘explores what people have read and why they have read it’, little, in the more than 1,000 pages that follow, support that assertion. It is rather a simplistic, superficial literary primer, aimed at readers who need to be told that

although today the term ‘epic’ is often employed to describe blockbuster Hollywood films, in antiquity, it referred to poems that followed certain rules and conventions

and that ‘Geoffrey Chaucer centred his best known work, The Canterbury Tales (c.1386-1400), on the theme of pilgrimage.’

Certainly no one will argue with these assertions, but their usefulness for someone seeking to understand ‘what people have read and why they have read it’, can be questioned. The synoptic timelines at the beginning of each section are helpful; most of the rest, for this reader at least, is not.

Comments