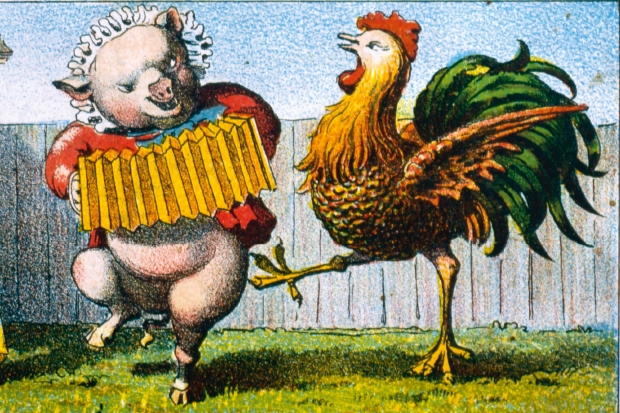

Here are two parallel books, both by Americans, both 260 pages (excluding indexes) long, both using ‘likely’ as an adverb. One looks at the history of the world through the story of the chicken; the other does the same through the story of the pig. Which would you prefer? I found the chicken one harder going — like ploughing through one of those brilliant but exhausting New Yorker articles that never seem to end, for which the journalist with too generous a budget has spent years interviewing hyper-specialist scientists in labs and ‘facilities’ across the USA — but I found the pig one sadder. There’s an illustration I had to cover up while reading page 174: of a pig being hauled onto a huge wheel, looking terrified, about to have its throat slit as part of an early pork-production line in 19th-century Chicago.

In the chicken book, you know that every chapter opening — whether it’s about the ancient city of Ur or a Greek vase — will lead up to the word ‘rooster’. Likewise, in the pig book, you know that every opening paragraph — whether it’s about Beowulf or the Greek physician Galen — will lead you to the word ‘pig’ or ‘hog’.

The chicken book hardly mentions pigs, and the pig book hardly mentions chickens, although both authors portray their chosen animal as central to the history of civilisation. One author counts the chicken bones at a dig in the Middle East; the other counts the pig bones at another dig in the Middle East; and each result seems to emphasise the supremacy of the author’s subject. Which just shows that you could put forward the story of the dog, the cat, the rat or the gumboot and your readers would accept your chosen subject as the driving force of civilisation if you wrote persuasively enough.

Never mind the chicken crossing the world: Andrew Lawler crosses it himself, visiting the corner devoted to chicken-bone samples at the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA; a cockfight in the Philippines (always to the death, and watched by huge cheering and betting crowds); a priest on a velvet sofa in Iraq who tells him about the chicken’s central role in the Yezidi religion; a factory complex in Dresden to which 360,000 eggs a day are delivered for the manufacture of the flu vaccine; the Natural History Museum annexe in Tring to look at Darwin’s chicken samples sent back from his voyages; countless US genome-investigating labs, university campuses in Michigan, and poultry farms; and a US rescue sanctuary for chickens, whose owner wears a T-shirt that says, ‘I dream of a society where a chicken can cross a road without its motives being questioned.’ All this, and much more, in the effort to work out exactly how and when in the last 20,000 years the red jungle fowl became domesticated. And did the chicken reach the USA from the Pacific (with the arrival of the Polynesians in Chile) or from the Atlantic (with the arrival of the Spaniards in the Caribbean)? The debate continues.

‘Only five foot three inches tall, Thutmose III’s conquests took him across the Euphrates River…’ That type of mismatch of subclause and subject of main clause grates in the chicken book. Mark Essig, the author of the pig book, is a more elegant writer, and it’s a relief to turn to the lower decibel level of his prose.

The Chinese character for ‘home’ he tells us, is formed by placing the symbol for ‘pig’ under the symbol for ‘roof’. Pigs and humans have lived together for at least 11,000 years, as the dig at Hallan Cemi in Turkey testifies. Every part of the pig’s anatomy has proved useful; the Romans feasted on ‘udder of lactating sow’ (which sounds like a line from three witches in Macbeth). The great thing about pigs is that they eat everything, including human waste: this has made them highly popular with some, who marvel at their ability to double as urban sanitation service and food, but has caused them to be derided and spurned by others from the more squeamish religions. Pigs reproduce fast and profusely: they have a four-month gestation period and up to 12 piglets — piglets which, as Essig can’t resist telling us, are ‘as intelligent, playful and curious as puppies’, which makes it all the more unbearable to read about their slaughtering through history in increasingly cruel conditions.

Leave a male and female pig on a shore, as the Pilgrim Fathers did, and they will feed and breed happily: when you or your descendents come back the next year there will be enough pigs to sustain a small town. Having pigs rootling about near the kitchen door used to be standard practice, right up to the 19th century: to have a sty in the garden was held to be as essential to the happiness of a newly married couple as a living room or a bedroom.

Both these books have succeeded in luring me away from the ‘striplit morgue’ of the supermarket for my next meat purchase, to the extortionate organic butcher.

Comments