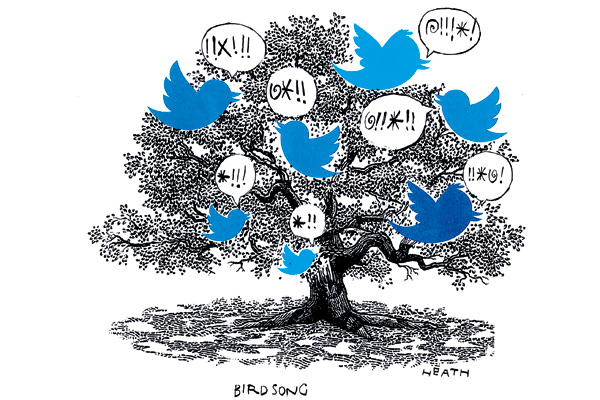

This is not to be a column about Twitter. Can’t abide columns about Twitter. I’ve written a few, I know, but this is not to be another one. I promise.

Time was, though, it was actually quite hard to find out what people thought, if they weren’t you. I mean, you could go out and ask them, but the process always ended with you being in a supermarket car park, and them being mental and not knowing what the Working Time Directive even was anyway. Twitter is a pipe of views coming straight to your screen. So explicitly not writing about it can feel like going out into the world with a bucket on your head, simply because you’re a bit bored of people writing about what they’ve seen with their eyes.

Anyway, the thing that happened this week on Twitter that this column, which is not about Twitter, is to concern itself with was a bunch of people threatening another person with rape. She was Caroline Criado-Perez, a woman who had campaigned to put Jane Austen on a banknote. They were… well, I don’t know. That’s rather the point. One of them, a 21-year-old man, has been arrested. Potentially he was almost all of them. Potentially not. Who knows? There was lots of outrage, either way, and lots of angry columns about how bad it is that people are bad. And this, just so we are remaining clear here, is not to be one of them.

The thing is, it strikes me that when a person goes online to threaten another person with rape for wanting to put Jane Austen on a banknote, there can logically be one of two things going on. Either this first person genuinely feels that making somebody scared that they might be raped is a justified and measured response to his sense of irritation about a presumed feminist victory over a banknote. Or he doesn’t think that at all, and he’s a moron.

I think the latter. Which is not, by the way, intended as any sort of defence or mitigation, because this isn’t to be that sort of column either. But I have a longstanding theory that people are inexplicably weird online, and that quite a lot of the trouble they get into while online is directly the result. It’s a guess, obviously, but most likely most people who threaten rape online are no more rapists than that plonker who threatened to blow up Robin Hood Airport last year was a terrorist. Nor, I’d also guess, would most of them ever dream of threatening a women with rape to her face, however upsetting her views about the decor of currency appeared to be.

So the great question becomes this: does the presumed shield of web anonymity make them feel emboldened to say the nasty things they truly think? Or does it make them feel, perhaps inexplicably, that they’re free to pretend to think nasty things that they actually don’t? Take Oliver Rawlings, who the Daily Mail tells me is 20 years old and a student at Nottingham University. Last week he also took to the internet to say nasty things about the vagina of Professor Mary Beard, a prominent classicist. Then he apologised, after the professor threatened to tell his mum. Chances are his mum knows now.

Only Rawlings could truly tell us. But there is a school of thought that says he’d have been thinking these thoughts anyway, in the pre-internet age, but merely not speaking them, and I simply don’t think that’s right. Rather, I actually doubt he’ll have honestly grasped how hateful he was being even while he was being it. Should have done, obviously. No excuse for not doing. But I just doubt he did.

We are getting no better at this stuff — that’s what is striking. We remain unsure whether an utterance online is a shout in the street or a scrawl on the toilet door or a joke between friends. Each one has to be all three. Which is not to say, of course, that there are no true villains out there, because I’m sure there are plenty. But those of us with public profiles, or who write for a living, are perhaps prone to overestimating how many of them there are. We complain of being beleaguered by ‘trolls’ but remain lousy at distinguishing between those who merely disagree with us, those who disagree with us but rudely, and those who express a desire to sever our head and keep it in a box. Because it all looks the same in cold hard print. It all has the same stature, whether it means to or not.

When I wrote about this phenomenon five or six years ago I thought it was a temporary stage; that the world would evolve an understanding of what could be acceptably said and where. But I don’t think that any more. All this will keep happening. Nasty people will keep saying nasty things, and we will all keep caring even when we shouldn’t, and nothing will ever change.

A hidden gem

But listen. I’m miserable. Years ago, I wrote a well-received but poorly purchased novel about a thief stalking high society and stealing jewels. Now, suddenly, a thief is stalking high society and stealing jewels. Last week he hit an exhibition in Cannes and made off with 100 million euros worth. ‘This is it!’ I thought to myself, when I say it on the news. ‘Seven years late, this is where it all takes off!’ Nobody has called. Not Londoner’s Diary, not Heat magazine. Not even Vanessa Feltz. Bloody unfair.

Comments