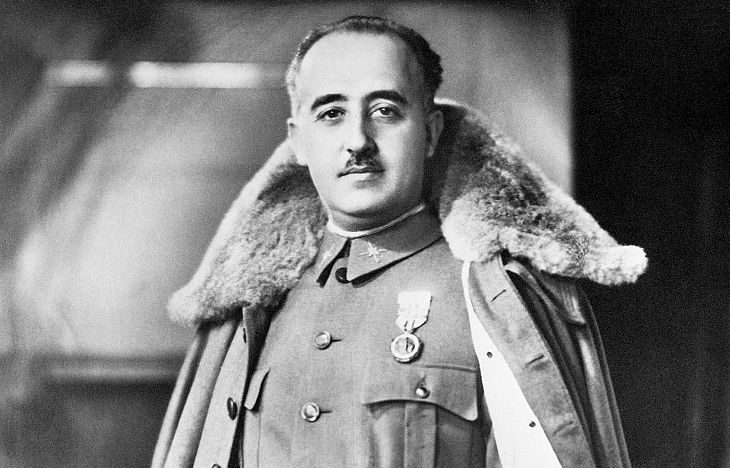

‘Fine weather in Malaga’ proclaimed the banner headline of a Spanish newspaper in 1974 – that was the day’s big story. There was nothing about the country’s social and economic problems or the Carnation Revolution bringing democracy to neighbouring Portugal. After almost four decades in charge, the dictator Francisco Franco had effectively depoliticised Spain. ‘A century and a half of parliamentary democracy,’ Franco said, ‘accompanied by the loss of immense territory, three civil wars, and the imminent danger of national disintegration, add up to a disastrous balance sheet, sufficient to discredit parliamentary systems in the eyes of the Spanish people.’

Yet once Franco died – fifty years today – a brief but remarkable period of consensus, compromise and reconciliation brought a rapid transition to democracy. A vibrant press catering for every political perspective sprang up as ‘the fresh air of freedom blew through all parts of society’ and Spain became one of the most socially liberal countries in the world. Living standards rose and the country’s Human Development Index score improved greatly.

Spanish society has become increasingly fragmented and exclusive

But as democracy was being established, mistakes born of haste and inexperience were inevitable. As a backlash to Franco’s centralism, the country was somewhat arbitrarily divided up into 17 ‘regional autonomies’, each with its own elected assembly. Today, then, Spain is governed at five levels: local, provincial, regional, national and European. It’s estimated that there are somewhere between 300,000 and 400,000 politicians – twice as many politicians as doctors. Franco would be horrified.

There are now nearly two million public servants in the regional bureaucracies – over 200,000 jobs have been created since 2018. Education and health services have been devolved and regions operate their own companies and broadcasting networks. The steady increase in administrative layers has driven up public debt while fostering corruption and inefficiency. One recent estimate is that well over a hundred pages of regulation are generated every hour.

Since one region’s licences and permits often aren’t valid in another region, small businesses find it difficult to expand beyond their home base. Meanwhile, the regions wrangle constantly with central government over the division of powers, responsibilities and finance. Coordination was conspicuous by its absence during both the pandemic and this summer’s wildfires. And Madrid and Valencia are still arguing about who’s to blame for the deaths of 229 people in the flash floods last year.

Spanish society has become increasingly fragmented and exclusive. In Catalonia, which in 2017 briefly declared independence, all state school teachers must be fluent in Catalan and a whole generation has imbibed a distorted ‘anti-Madrid’ version of history. And, since the central government often depends on the support of regional parties, Spain suffers from a parochial, inward-looking political culture.

Last year’s Pew survey showed that close to 70 per cent of Spaniards are dissatisfied with their democracy. It’s hard for ordinary people to access public contracts and government reports; a Franco-era law allows documents to be kept secret for ever. Citizens aren’t even trusted to vote for individual candidates – only for a party. So, while the votes cast determine how many councillors and MPs each party will get, the party leaders decide who those councillors and MPs actually are. Since they owe their well-paid, undemanding jobs to their leader not the electorate, most politicians are sycophantic ‘yes men’.

And it’s not only the politicians whose livelihoods depend on immediate, unquestioning obedience. When the socialists took office in 2018, some 6,000 public servants were promptly purged. Incoming prime minister Pedro Sánchez parachuted hand-picked party loyalists into plum posts at the state-run broadcasting company, the state-owned hotels and, of course, the state pollster. The polls have been biased ever since.

The post-Franco spirit of consensus and cooperation has disappeared and the quality of the politicians has declined rapidly. The Minister of Transport in the socialist government, who seems happier trading playground insults than doing his job, recently charged his team – paid of course with public money – with collecting and cataloguing the abuse thrown back at him (195 pages’ worth apparently). William Chislett of the Elcano Royal Institute, a Madrid think-tank, concludes: ‘Political life has become woefully polarised, making the consensus that would enable structural reforms to be achieved for the benefit of the greater good impossible to achieve.’

The politicians are forever being caught out in lies. In the 1980s and 1990s, the socialists denied all knowledge of the state death squads targeting ETA, the Basque terrorist organisation – right up until the convictions. In 2004, the right-wing government tried to pin the Madrid train bombings on ETA – a cynical fiction sustained even as the evidence pointed unmistakably to Al Qaeda.

Today Pedro Sánchez’s socialist-led minority government is immersed in corruption scandals. After Franco, the socialists promised ‘a hundred years of honesty’ but instead have demonstrated spectacular venality and contempt for the law. Meanwhile, right-wing politicians claim with breath-taking effrontery that their vast corruption scandals prove that actually they are very honest: ‘You see, it never even crosses our minds that a few bad apples might be doing these terrible things.’ Meanwhile, the trial of the family of Catalan nationalist Jordi Pujol, who headed his region’s government for 23 years, is about to begin. Pujol and his seven children face long prison sentences if found guilty on corruption charges.

But Spain’s corrupt politicians rarely seem to spend long in prison. Around 1,800 politicians (compared to just one in Portugal and Italy) enjoy ‘aforamiento’, meaning that, unlike ordinary citizens, they can only be tried in the highest courts, where their cases often remain unresolved a decade after the events occurred. While 32 countries have significantly improved their corruption score since 2012, Spain has dropped dramatically, from 30th in Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index to 46th position – below Botswana and Rwanda.

In the 20th century many Spaniards, acutely conscious of how politicians had failed their country, put their trust in General Franco. Today many pin their hopes on the European Union. In Malaga, meanwhile, the weather’s still fine.

Comments