‘It is impossible that you should not have sensed,’ wrote Wagner to Ludwig II shortly before the first performance of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, ‘under the opera’s quaint superficies of popular humour, the profound melancholy, the lament, the cry of distress of poetry in chains, and its reincarnation, its new birth, its irresistible magic power achieving mastery over the common and the base.’ The King, and anyone else, might well not sense that in the latest revival of Graham Vick’s production of the opera at Covent Garden.

Always a toy-town affair, with little high-roofed houses and distant spires, all lit in glowing colours, and an oppressive cheerfulness reigning over all the characters, it has now become at best cute and often a lot worse than that. ‘I feel as if I’m about to drown in Gemütlichkeit,’ someone said to me in the second interval, and I saw what he meant, though I was feeling unusually gemütlich myself. Even the brawl at the end of Act II, which should be terrifying, not only in its suddenness but also in its brutality, is mostly a romp, though David clobbered Beckmesser with moderate enthusiasm.

If you prod Die Meistersinger at virtually any point, you see that it is dealing with the relationship between surfaces and depths, even Beauty and Truth, and the place that art, and especially new, novel art has in relationship to these troublesome couples. Art is illusion — Sachs says in his marvellous scene with Walther in Act III that all art is true interpretation of dreams — but so is everything else that we usually deal with, so it is the job of the reflective person, such as Sachs, to distinguish between good and bad illusion, to foster the first and if possible eliminate the second. That’s hardly something that the townspeople are going to understand, and Walther is not of a philosophical turn of mind either, so the sophistication of the great Wahn (‘madness’ or ‘illusion’) monologue is something that Sachs shares with the audience, and that a great director will, with skilful touches, help us to grasp and think about.

But where is such a director now? Either they tend to go the way that Elaine Kidd has taken a production which never scratched the surface very hard, or they labour to deal with the alleged political undertones of the plot, an utter red herring. Richard Jones in Wales gave intimations of a deeper sense of the work, but uncharacteristically pressed no further. So at Covent Garden one watched innocuousness and hoped for illumination from the music. And to a very large degree this Meistersinger did what one can reasonably hope for from any performance: give an overall impression which is more, much more, than the sum of its parts. Nearly every performance I have been to, or recording I have listened to, has had one or more fairly serious inadequacies, and yet has left me feeling as one should at the end of this work.

This was Antonio Pappano’s first account of Meistersinger, and no doubt it will improve in various ways. It is still by far the best Wagner interpretation I have heard from him. The Overture got off to a magnificent start, swept forward with grand resolution, but had time for many usually unnoticed details; and the whole first act, which can easily fragment, moved effortlessly forward, though its final climax, like that of the other two acts, was less cathartic than it should be. But the predominant chamber-textures of the scoring were almost all exquisitely realised.

Among the singers, Toby Spence’s David stood out as almost ideal, both in acting and in his impeccable singing. As often, I wished David had been singing Walther, instead of teaching him badly. Simon O’Neill, who seemed so promising, has developed into a tight-voiced singer and a wooden actor, though he managed some of his set pieces well, if not his public rendering of the Prize Song. Eva is at last in the hands of a singer with a big enough voice to encompass the role’s few opportunities for letting rip, and Emma Bell also led the Quintet movingly.

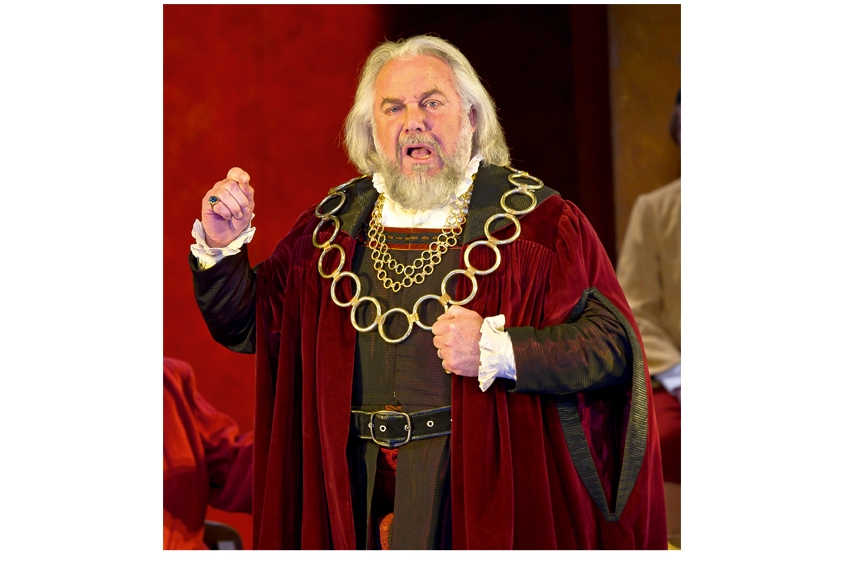

John Tomlinson has moved from Sachs to Pogner, but — at least on the first night — his voice was a ruin of its former self, even earlier this season, when he was a great Gurnemanz. Wolfgang Koch, the new Sachs, has a lot to learn about the role, but he at least realises that he has to have enough voice to bring off all his meditations and orations in Act III, and he did them commendably, if not memorably. Now he needs to make the most of the previous acts too. The outstanding Master was Donald Maxwell’s Kothner, fully in command of his coloratura. Peter Coleman-Wright seemed so intent on not overdoing Beckmesser’s complex character that he fell rather short, but sang well. It’s the usual kind of balance sheet but, despite loathing almost every aspect of this ghastly time of year, I loved the performance and felt grateful for it.

Comments