‘Everything obscene comes from France,’ wrote James Dixon, an eye surgeon retired to Dorking, in 1888. He was provoked by learning of an item called a condom, and explained to his correspondent, James Murray, that this was ‘a contrivance used by fornicators, to save themselves from a well-deserved clap’. Surely the word had no place in the Oxford English Dictionary, of which Murray had for the previous nine years been editor? Murray was persuaded and left it out. Dixon was a useful source of information about words relating to medicine, and Oxford’s team of under-resourced lexicographers relied on the goodwill of such volunteers.

Ogilvie’s book is an engaging sideways look at one of the great monuments of erudite collaboration

Sarah Ogilvie’s sprightly book celebrates the OED’s unpaid contributors. The first advertisements inviting readers to be part of ‘this truly national work’ appeared in 1857, and 166 years later the OED still periodically appeals to the public for help. But Ogilvie concentrates on the ‘ordinary people doing extraordinary things’ to gather material for the first edition, published in instalments from 1884 to 1928. She is able to shed light on this because in 2014, while killing time in the dictionary’s archive, she chanced on a small black volume tied with a cream ribbon. This was Murray’s address book. Its pages hum with pithy judgments on the individuals who promised much, yet failed to deliver (‘gave up’, ‘gone away’, ‘no good’, ‘nothing done’). They also illuminate the labours of an army of the linguistically alert and curious-minded – a total of 3,000, in Britain and America as well as South Africa, New Zealand, the Congo and Japan.

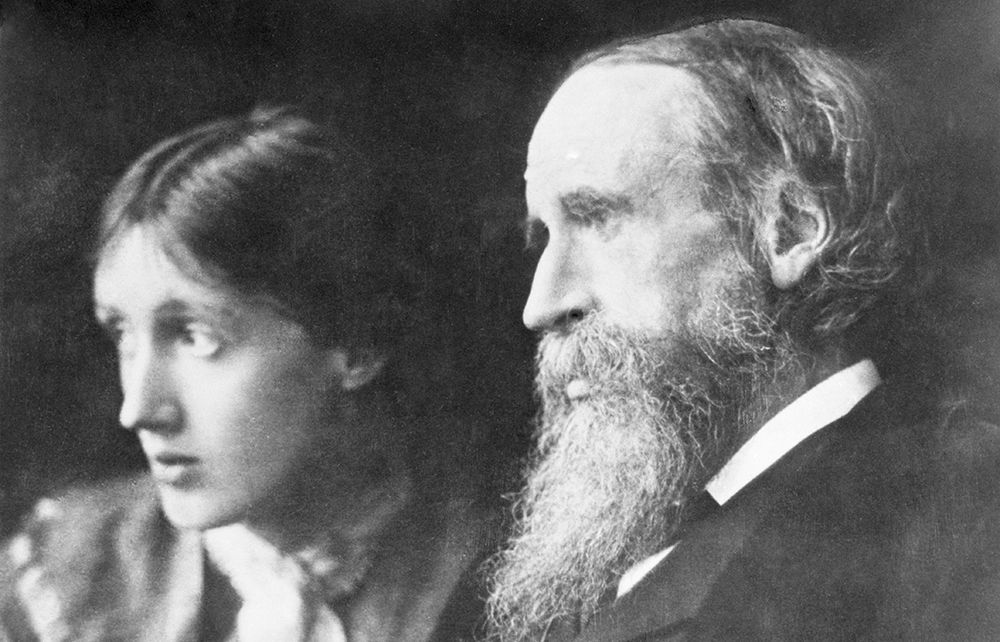

Some are familiar: Virginia Woolf’s father, Leslie Stephen, the first editor of the Dictionary of National Biography; Eadweard Muybridge, whose images of galloping horses and boys playing leapfrog were landmarks in the photographic study of motion; and the translator Eleanor Marx, daughter of Karl. The best known, thanks to Simon Winchester’s account of him, is William Chester Minor, a doctor imprisoned at Broadmoor and troubled by sexual hallucinations which ultimately caused him to lop off his own penis. Yet the OED was, as Ogilvie puts it, ‘a project of the crowd, the autodidacts’. We encounter not Charles Darwin or William Morris, Oscar Wilde or Beatrix Potter, but instead the likes of the astronomer Elizabeth Brown and her sister Jemima, who cared for their elderly father in the Cotswolds, and the splendidly named London schoolmaster Tito Telemaco Temistocle Terenzio Pagliardini.

Readers seeking the full story of the project will want to consult Peter Gilliver’s impressive The Making of the Oxford English Dictionary (2016). But Ogilvie’s book is an engaging sideways look at one of the great monuments of erudite collaboration. In 26 chapters running from A to Z (H is for Hopeless Contributors, V for Vicars and Vegetarians), it pays generous tribute to figures such as Abraham Shackleton, an employee of a tram company in Birkenhead who mined the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Frederick Elworthy, scion of a family of woollen manufacturers, who knew a vast amount about folklore and coined the word ‘ophiolater’ to denote a person who worships snakes.

Clifford Beakes Rossell of New Jersey carefully read for the OED a history of the 15th-century warrior Charles the Bold; otherwise he was notable for developing a kind of elliptical sewage pipe that could ‘accommodate… maximum flow’. Herbert Spencer Ashbee had the trying tic of selecting racy quotations to illustrate the most humdrum words – not a huge surprise, since he owned the world’s largest collection of erotica. Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper, friends of the sexologist Havelock Ellis, were aunt and niece as well as a lesbian couple, and sent examples from the poems of another of their friends, Robert Browning, who according to Murray ‘constantly used words without regard to their proper meaning’. He had a point: Browning’s misunderstanding of a 17th-century text led him to suppose that a ‘twat’ was a garment worn by a nun.

Among the book’s brightest characters is Alexander Ellis. His areas of expertise included algebra, acoustics, barometers and spelling reform. Except in summer, he wore a greatcoat known as Dreadnought, the 28 pockets of which contained a corkscrew, two sets of nail scissors and even an emergency scone. Utterly idiosyncratic in appearance — he insisted on wearing shoes that were three inches too long — he was nevertheless sociable and genial. Ogilvie, originally a computer scientist, has carried out data analysis to identify the OED’s ‘super-connectors’, who proved most influential in involving others. Ellis ranks first. Like the other heroes of The Dictionary People, he has remained largely ‘unsung’ because he espoused an ideal of unobtrusive public service. Aptly, he displayed on his desk at home in Kensington a quotation from the philosopher Auguste Comte: ‘Man’s only right is to do his duty.’

Comments