It is more than ten years since Natasha Walter published The New Feminism, a can-do look at the ‘uniquely happy story’ of the women’s movement.

It is more than ten years since Natasha Walter published The New Feminism, a can-do look at the ‘uniquely happy story’ of the women’s movement. Then she urged the sisterhood to cast aside the puritanical fixations of yesterday and instead concentrate on politics, pay and the right to work part-time for a year or two without being left behind. At the time I was one of the several crosspatch hoodies who said ‘steady on: patchwork careers are all very well, but what about the uses and abuses of pornography?’ It’s good to see that Walter has now changed her tune. I got it wrong, she proclaims at the beginning of Living Dolls, arguing that the hypersexual culture in which we live is a sign not of equality but its opposite.

As a moral pamphleteer Walter is a vivid chronicler of the culture she deplores. Here is her description of a ‘babes on the bed’ competition organised by Nuts magazine at a club in Southend in the spring of 2007. ‘The first woman to get on the platform was a confident girl with long, fair hair, in high-heeled boots and hotpants, holding a microphone.’ She is introduced by the DJ — ‘This is Cara Brett! She’s on the cover of Nuts this week! So buy her, take her home and have a wank.’ The introduction is completed and Cara takes over. Walter watches:

In the pages which follow, Walter talks to Cara, who comes to the interview with her best friend beside her. Cara earns a living as a ‘glamour model’; the best friend is a law student at university, but fully supportive: ‘It’s in a magazine that people choose to buy — you don’t have to buy it’.

Walter notes that the ‘emphasis on choice is key’. Small wonder, then, that she reports in triumph when Cara’s house of cards collapses into a not quite so uniquely happy confession: ‘A lot of girls don’t know how to make choices. They think that because one girl’s doing it, and everyone’s going wild, they should do it. Maybe that will change one day.’

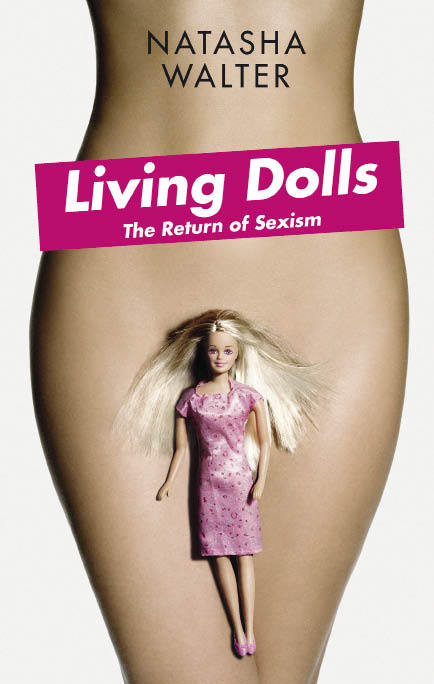

Walter doesn’t share that wistful hope. Not unless women regroup to reclaim the night, and mothers save their daughters from the sea of candyfloss pink that begins the conforming rot. This surprising yoking together of causes large and small is the most original aspect of Walter’s argument. One doll leads to another — the unprecedented accessibility of internet porn has bred a generation of girls who take their lessons on how to look from the hairless whores with silicone implants they are accustomed to seeing on screen.

The first half of Living Dolls consists of a series of sketchy interviews with girls and young women, students and sex workers, in which the mantra of choice is ripped away to reveal an ersatz world of copycat promiscuity, dieting and plastic grooming which bears little relation to desire and none to empowerment. But still the surveys show a pronounced tendency among the young to see Jordan as a role model. And no wonder, is the conclusion which Walter doesn’t quite spell out, given the way girls are seduced into identikit fashions from an early age. The mother of a daughter herself, Walter is good on the tendency of parents to ascribe the same characteristics differently according to the sex of their children. She goes to a party where a shy, clinging girl is described as quiet and good, while the boy who also opts out is a restless handful.

Walter is less convincing in the second half of the book, when she turns her guns on the scientific literature concerning sex difference. One academic study is pitched against another with wearying inconclusiveness, while the media are in the dock for making news out of difference rather than sameness. But the reason that difference is news is because it is sameness which, quite rightly, must be legislated for. As long as the pieces are in place for any girl who wishes to study engineering, how much should we bother with the left brain/right brain, nature/nurture ping pong so beloved of bores the world over?

I thought this anyway, but with better foundation, after reading Walter’s exposition of the ‘Stereotype Threat’ evidenced by experiments showing that differences in empathy levels between men and women disappear when the subjects don’t know the reason why they are being assessed. Once we accept that much (so-called) research fails to screen out our unconscious determination to conform to social norms we can relax into throwing away both baby and bathwater.

Comments