Perhaps to contradict the shocking fade-out of sculpture post-1970 in the Royal Academy’s Modern British Sculpture exhibition, just ended, there are a number of good sculpture shows in the commercial galleries.

Perhaps to contradict the shocking fade-out of sculpture post-1970 in the Royal Academy’s Modern British Sculpture exhibition, just ended, there are a number of good sculpture shows in the commercial galleries. A survey at Waddington’s of Bill Woodrow’s witty recycled works from the 1980s ends on 16 April, but over the road is a fine display of recent prints and sculpture by Ivor Abrahams (born 1935), entitled Suburban Encounters (Mayor Gallery, 22a Cork Street, W1, until 28 April). Abrahams is our greatest interpreter of the suburban dream, whether it be the kempt lawns and borders of the gardens, the trophy window boxes and gables of the houses, or the edging into night-time activity (the hidden and the unconscious), here symbolised by the owl.

Go through to the back room at the Mayor Gallery and gaze down into the pit below: in the lower sculpture gallery is a group of works which perceptively anatomise our dreams and realities in imagery spiced with humour, oddness and originality. An abiding theme is the threshold: inside and outside, doorways, differences in looking — Abrahams invents textures and shapes to deal with the sloganised and graffiti-spattered façades of modern life.

His structures resemble seaside kiosks or totem poles, monuments to the extraordinariness of daily existence. ‘Hatton Cross’ is a stainless-steel cross faced with the copper etching plates used to make the large totem print hung nearby. The painted bronze ‘Tudor Totem’ varies the traditional black and white with pale greeny-blue, and proposes a new and slightly sinister category for Osbert Lancaster’s itemisation of popular architecture.

Abrahams’s interest in the lurid and macabre is further explored in an exhibition of two suites of prints he made in the 1970s, currently on show in the Tennant Gallery of the Royal Academy (until 22 May). One is devoted to E.A. Poe, the other to Edmund Burke, and the display — full of hourglasses, skulls, funerary monuments — is appropriately called Mystery and Imagination. Abrahams’s career is ripe for reassessment.

Another artist fascinated by the sublime, and of the same generation, is John Hoyland (born 1934). His exhibition of new paintings is entitled Mysteries (at Beaux Arts, 22 Cork Street, W1, until 7 May), and is testament to the unflagging verve with which this remarkable artist greets the challenge of growing older. Hoyland is a highly individual colourist whose inventive approach to working in acrylic sets even fellow artists wondering how he does it. Years of experiment have equipped him with a technique capable of exploiting and controlling chance, while his naturally audacious and restless spirit has ensured that he rarely repeats himself.

All is variation, inquiry and unexpected subtlety among the poured and thrown pigments. The work is as much about emotional states or intergalactic space as it is concerned with the shapes and textures made by the determined application of paint. Intriguingly, many paintings in this new group feature a cross: is it a cancellation or a multiplication sign, a kiss or ‘x marks the spot’? It is all of these and none, both negative and positive, dark and mellow, the cross beneath the skin. However, the cumulative effect of this show is undeniably joyful: a great, though not naive, affirmation of life, like the forward stride (but backward glance) of the exuberant ‘Saffron Medusa’.

Another great life-enhancer is William Nicholson (1872–1949), celebrated now in a splendid show at Browse & Darby (19 Cork Street, W1, until 6 May). Although mostly a loan exhibition of very high-quality works, there are also some items for sale, including drawings and prints, but the bulk of the show consists of exquisite still-life paintings. Browse & Darby has done much over the years to promote Nicholson, and the catalogue reprints the late Lillian Browse’s 1995 essay on him.

‘The Duchess of Cork Street’, as she was affectionately nicknamed, knew Nicholson and she recalled his habit of picking up hair-pins in the street and using them later to scratch alterations to a painting. ‘Granada Window’ (1935), an atmospheric and curiously textured picture, looks as if it might have suffered such attentions. Others here are so perfectly pitched, it’s impossible to imagine them being revised. ‘The Silver Casket’ (1919) is a good example of this, as is the small but potent ‘Fuchsias in a Blue and White Jug’ (1909). On the whole, the still-lifes make a greater impact than the figures or landscapes, with the notable exceptions of ‘The Lepers’ Walk’ (1906) and the beautiful ‘El Arroyo in Flood’ (1935).

Jack Milroy (born 1938) is a very different kind of artist, a sometime surrealist and scourge of the indulgent society, a satirist of contemporary attitudes and received opinions. He makes cut-out sculptures from paper or transparent polyester sheet, filling cabinets with thronging forms, which might refer to other artists (such as Hieronymus Bosch, whose ‘Garden of Earthly Delights’ gives this exhibition at Art First, 21 Eastcastle Street, W1, until 30 April, its title), or to the condition of social and economic meltdown we find ourselves in. His interleaved sheets of imagery, abstract or representational, take a great deal of deciphering if you wish to trace their narrative or formal complexities rather than rely merely on their initial impact.

Aside from the Magrittian snakes, the Calder pop-up and the deconstructed Jackson Pollock, Milroy tends to a strong narrative which alternately conceals and reveals. His work is a sum of mutilations: an intuitive transformation of existing imagery, in which the ideas emerge from the process of cutting and reordering. Bat-like bankers behind umbrellas meet Bosch, Gucci and the Kama Sutra or a Japanese book of wild grass drawings spills its paper-chain of leaves in elegiac restraint.

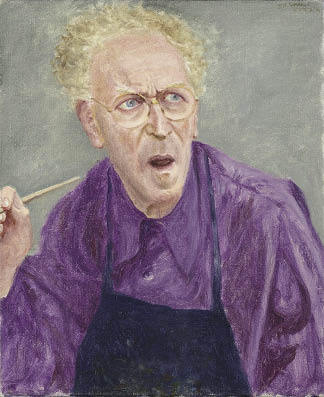

At Marlborough Fine Art (6 Albemarle Street, W1, until 7 May) is a memorial show for Avigdor Arikha (1929–2010), the Paris-based artist who began as an abstract modernist and converted around 1965 to figuration. Artists usually traverse the opposite track, starting figurative and becoming abstract (Victor Pasmore, for example), so it’s refreshing to encounter an exception. Arikha was a very considerable draughtsman, as can be seen from the prints and drawings here, and a painter of precise details. He seems to owe something to the landscapes of Morandi (see his ‘Mount Zion, The Dormition’, 1991) and insisted on completing a painting on the day it was begun. This led to some vigorous brushy renditions, among which the near-abstract ‘Corner of the Studio’ must stand supreme.

To return to sculpture, I cannot recommend highly enough Nigel Hall’s latest show, entitled The Spaces Between, at Annely Juda (23 Dering Street, W1, until 14 May). This is his tenth solo exhibition with the gallery, and quite possibly his best yet. The visitor to this elegant top-floor space is greeted by a single wooden sculpture of breathtaking beauty placed on the end wall. This is ‘Compass’, a double loop arcing up the wall in polished grey-white birch veneer, curving upwards like an enigmatic smile. Around this memorable piece is a compelling group of new works: sinuous gouache and charcoal drawings, wood, bronze and steel sculptures of interlocking and congruent shapes, all informed by an inspired simplicity. This is Hall at the height of his powers.

Comments