Benjamin Balint’s Kafka’s Last Trial is a legal and philosophical black comedy of the first water, complete, like all the best adventure stories, with a physical treasure to be won or lost. Balint lays out with cool, collected passion the full absurdity of the 2011 court struggle which climaxed when a couple of boxes of aged, yellowing jottings, upon which an elderly Tel Aviv lady had allegedly allowed her cats to sit for many years, were taken under armed guard, besieged by writs and counter-writs, to the highest court in Israel.

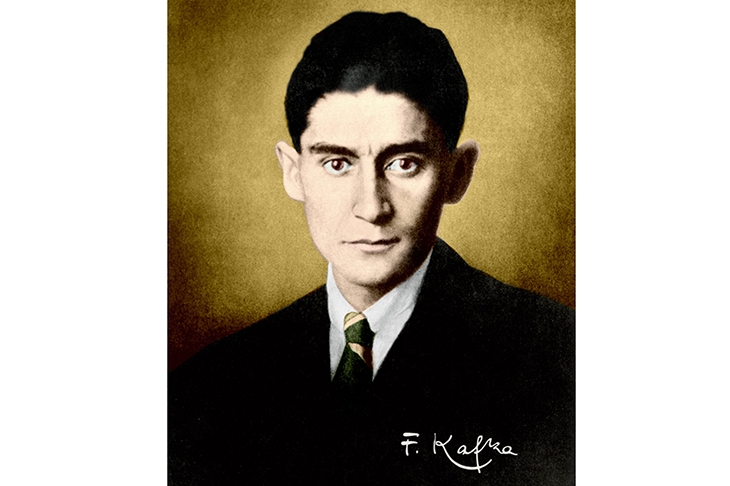

Until 1973, you see, these boxes had belonged to Max Brod, best friend of Franz Kafka, the legendary Nostradamus of Prague who (as any fool knows) somehow predicted the Holocaust. Scholars had gradually become convinced that they might hold great unpublished works. At the risk of bragging, I did warn people on Newsnight in July 2010 that they wouldn’t (they don’t), on the simple grounds that if they did, Brod, founder of the worldwide Kafka industry, would certainly have published them decades earlier.

Balint’s agenda isn’t to debunk Brod, or his myth of Kafka. He still cleaves, indeed, to the hoary legend that Kafka was almost unknown in his lifetime. In 1915 The Metamorphosis and The Judgement were given the prize-money from Germany’s biggest literary award in a bizarre insider deal, and Kafka’s publishers followed up with a full-page advert which cited five glowing reviews, all of them by friends of Kafka’s and/or Brod’s. So, not very unknown at all. But this doesn’t matter, because Balint’s book isn’t for the tiny world of Kafka scholars. It’s really a deep yet entertaining look at something we should all care very much about: the absurdity of our modern obsession with ‘authenticity’ and ‘ownership’.

Now, I’m not sure if readers of The Spectator have quite realised yet that history, literature and culture no longer exist. These days we only have splintered micro-cultures, micro-histories and micro-literatures which officially belong to one sub-group or another. These groups (like Protestant sects after the Reformation, they multiply almost daily) tell the rest of us that we have no business with their culture, history or literature. So there is now an Israeli Kafka, a non-Israeli Jewish Kafka, a German Kafka, German-Jewish Kafka, and maybe even a Czech Kafka. Or perhaps some mixture of all of them. But there is no such thing as just Kafka.

My own tutor, Sir Malcolm Pasley, was sadly unaware of this. In 1961 he persuaded Kafka’s heirs by convoluted descent (the family having been practically wiped out in the Holocaust) that if they let him bring the manuscript of The Castle and the bulk of the diaries and occasional jottings to Oxford, he and the Bodleian library would preserve them, love them and produce scholarly editions of them, for the use and edification of all mankind. So in 1981, in his rooms in Magdalen, Pasley allowed me, despite my being a mere undergraduate who was neither German nor Jewish, to look at with him, and even very briefly to hold, the original manuscript of The Castle.

My God, what an outrage! By what imperialist, colonial or other ghastly law could a mere English baronet claim any kind of custodianship of the works of this German genius? Or should that be German-Jewish genius? Or perhaps Czech-Jewish genius? Czech-German-Jewish?

Balint skilfully lays out the madness going on here. He does full justice to the matchless tragedy of Germany Judaism while turning a cool, at times almost disbelieving gaze on the absurdity of the modern battle. So, is anything written by anyone Jewish, in any age, now the rightful property of the state of Israel, even if the Jewish writer in question never set foot outside Europe? Or do works written by a German-speaking writer who was completely steeped in German literature truly belong in Germany, even though the German state would have gassed him (as it did Kafka’s sisters) if he hadn’t died first? Or perhaps Kafka truly belongs to Prague, the city where he spent almost his entire life — but where, in his day (hard as it is to recall) the people throwing stones at the Jews were Czechs, while the mounted police quelling the anti-Semitic rioters were given orders in German?

Of course, there’s another answer, and it’s the one Pasley would no doubt have given: the only reason anyone is interested at all in those cardboard boxes of yellowing papers, or in the life and letters of one Dr Franz Kafka, is that we quite rightly place his works (the most substantial of which would never have been read by anyone, but for Brod) as among the most fascinating literary productions of early 20th-century Europe: books which belong to us all.

Comments