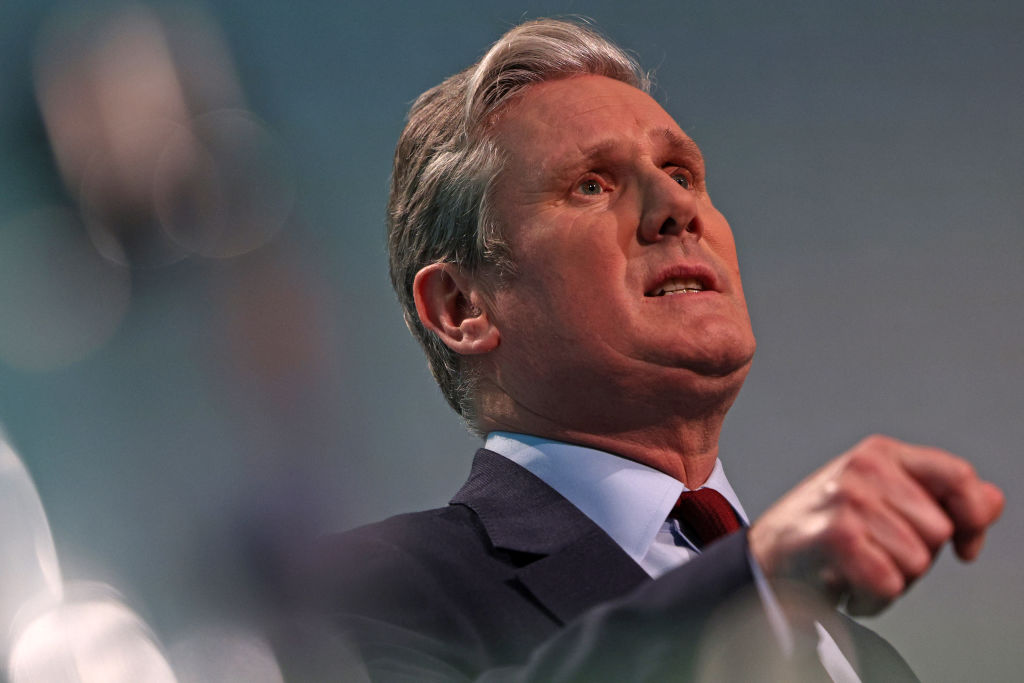

Keir Starmer wants to set expectations early. Speaking at the Resolution Foundation’s economy conference later today, the opposition leader used his speech to emphasise just how little scope he’d have at the start of any Labour government to splash the cash. His party will not ‘turn on the spending taps’, he told an audience of economists and policy analysts. Anyone expecting them to do so is ‘going to be disappointed.’ The speech seemed to deliberately echo the infamous ‘I’m afraid there is no money’ note left for the incoming Tory government by a Labour minister.

Starmer responded to the spending trap laid out in the Autumn Statement last month: where Chancellor Jeremy Hunt used almost all his fiscal headroom to cut taxes rather than boost public sector spending. As a result, the Office for Budget Responsibility has forecast a £19 billion hole, as inflation has – and continues – to strip departments of their spending power.

The government’s defence of this spending hole is that it thinks it can be filled with productivity gains rather than additional cash, with Hunt promising back in October to aim for 0.5 per cent gains in the public sector, which would translate into billions of pounds saved. Starmer addressed this too, insisting that ‘raising Britain’s productivity growth’ would become ‘an obsession’ of his party.

‘Having wealth creation as your number one priority, that’s not always been the Labour party’s comfort zone’, he noted, in another bid to push Labour’s more moderate economic credentials. But productivity gains weren’t his only answer. He also had an accusation to dish out: that the Tory ‘record over the past 13 years will constrain what a future Labour government can do’.

In other words, any perceived austerity taking place under a Labour government, Starmer wants to pin on his predecessors. He’d be inheriting an economy, he is set to claim, ‘worse than the 1970s, worse than the recessions of the 1980s and 1990s, and worse even than the great crash of 2008’.

But will voters agree that Labour’s hands are completely tied? Starmer and his shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves could, in theory, find more cash if they were to reverse the tax cuts announced last month, or usher in new ones. This is exactly where the Tories were hoping to apply pressure ahead of an election: forcing Labour to make clear what action it would take to find more money for public services.

It seems, for now, Starmer doesn’t plan to take the bait, and instead will point the blame back at those currently in charge. It could work for some time. But even under the projected spending crunch, public sector net debt is still steadily increasing, expected to reach £3 trillion by the end of the decade.

Furthermore, Starmer couldn’t help but introduce a big dose of interventionism, spelling out slightly more what Reeves’s ‘securonomics’ agenda includes. So far, it seems to mean a lot more state interference in the economy. Starmer said that ‘government can and must shape the mission…shape the markets’, with bigger industrial strategies, to reshape the economy to ‘better serve working people.’ It’s the kind of vague language that can put workers and businesses on their guard, who, through experience, have come to doubt descriptions of the state as a ‘careful steward’, as Starmer described it today.

With Whitehall already collecting more tax receipts and spending more money than ever before, Stamer is likely to come across similar questions being put to the Tories right now, especially given his zest for growing the size of the state: where exactly is the money going to come from, and why are taxpayers getting less and less for their growing contributions?

Comments