Keir Starmer looked blank. The shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, seemed confused. Only the old Stalinist Seumas Milne seemed really to understand.

It was 2019. Labour’s front bench team, and their leader Jeremy Corbyn’s close advisers, were being upbraided – from the left. Why were they putting the interests of international capital ahead of our workers? Why were they abandoning the chance to implement a meaningful industrial policy? Why were they giving up on the chance to save British steel, to give all support necessary to our manufacturing sector, to make a stand against neo-liberalism?

The person in the room making the challenge, over ginger beer and sandwiches, was not Owen Jones, James O’Brien or Mick Lynch. It was me.

The occasion was one of the ill-fated talks between Labour and the government in the last days of Theresa May’s premiership. Our failure to command enough Conservative votes to get a Brexit deal through parliament had driven the cabinet to see if compromise was possible with the opposition. It was never likely to be. But the government was running out of time, opportunities and indeed ministers, so one last throw was attempted.

Most of the time I kept uncharacteristically schtum, except for one moment when the tragically limited, anaemically timid, intellectually impoverished, morally pusill-animous, pre-emptively cringing nature of Labour’s position provoked me.

Starmer was once again laying down Labour’s ‘red lines’. To nods from his colleagues, he stressed how important it was to be in the European Union’s single market. In other words, to accept that a newly sovereign Britain could not control its borders, could not direct investment to infant enterprises, could not alter regulations, could not change procurement rules to favour British business, and in all these and thousands of other areas would have to accept foreign jurisdiction.

‘I’m sorry,’ I replied, ‘but I thought the whole point of Labour, the whole purpose of its creation, was to allow democratic control over capital? The single market was designed to fetter the discretion of democratically elected governments and allow business interests to prevail over the popular will. It’s only outside the single market that a UK government can decide UK economic policy in the interests of UK workers… That’s why Labour were committed to withdrawal in 1983. That’s why my parents voted Labour then.’

There was a brief silence. Looking at the blank eyes opposite, I realised that for all the understanding they showed, I might as well have been speaking in Russian. Indeed, given that only the avowedly Marxist Milne seemed to appreciate the point I was making, I wonder if I might have been.

The rest is history – or politics. Theresa fell. Boris got Brexit done. Then he got done. Liz succeeded him in September 2022. That was the only time the word ‘succeeded’ was attached to her name that year. She was followed by Rishi, who tried to tie up some of the loose ends Boris had left, before the Tories fell to their lowest tally of seats in the Commons since 1832.

This week’s agreement with the EU isn’t so much a reversal of Brexit as a refusal to see why it happened

And this week Starmer fell – into the embrace of Ursula von der Leyen. Brexit was a journey he’d never wanted to go on, and now he was coming home. Like a curate who’d been taken on a stag weekend against his better judgment, had his return ticket ripped up by the lads and thought he’d never see a sober evening again, he was, at last, after far too long queuing at the airport, back home in the arms of his fiancée. No more waking up to Brexit hangovers.

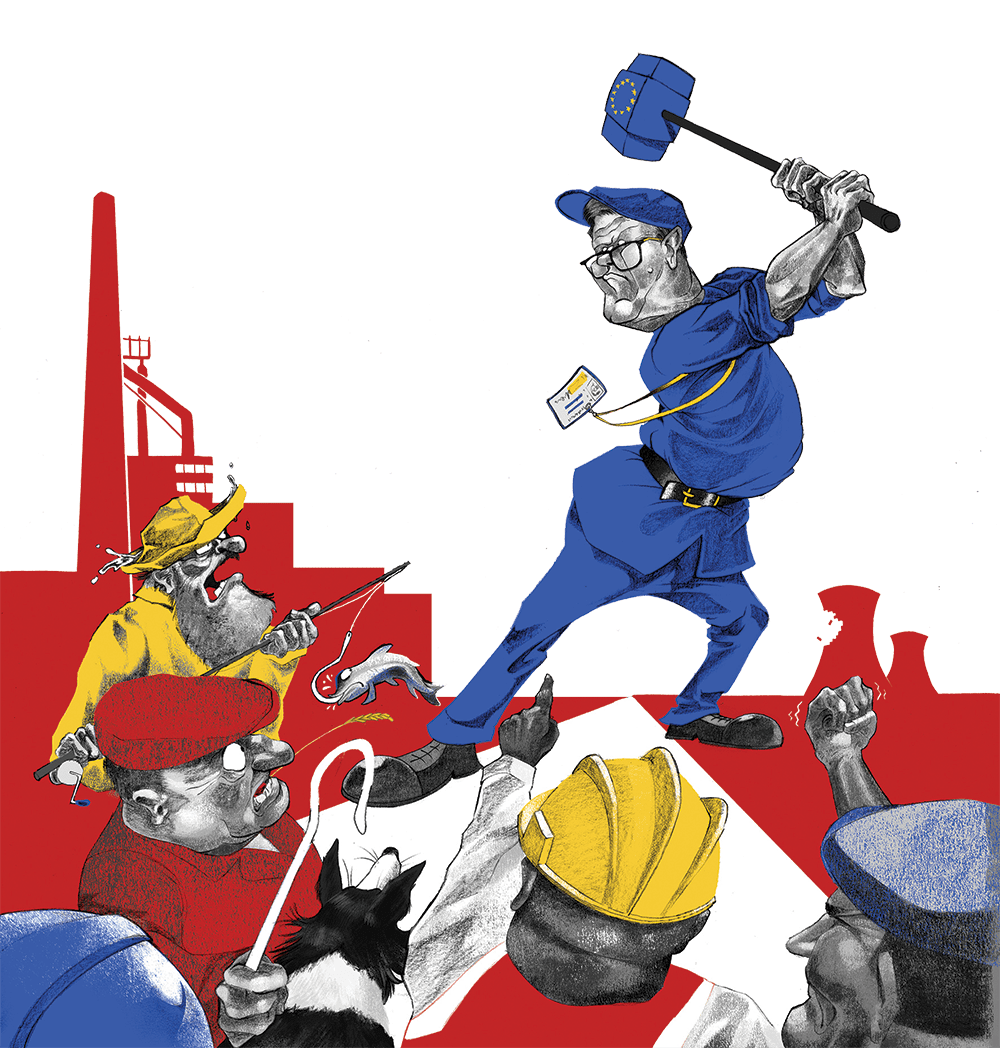

I understand why Starmer feels as he does. It’s in the nature of the priesthood of professionals to feel at home in the bureaucratically ordered world run from Brussels. The EU’s empire of complex and opaque rulemaking, in which legal directives and financial instruments can be constructed without the public having to know what’s being done or who’s paying the price, is honeyed perfection for the credentialled and connected. Whether you’re a human rights lawyer or a Goldman Sachs banker, Britain’s withdrawal from the EU meant the system that insulated you from the vulgar attentions of the people was ripped apart.

But Labour doesn’t, or at least shouldn’t, exist to make the lives of the fortunate more favourable. It’s there to wrest control away from elites and return it to the people, to make power accountable and to use the state to build a fairer society. That’s why generations of Labour politicians have been opposed to the EU project. They have known that it prevents a democratically elected government from being able to fulfil its mandate and shift power towards working people. It’s not just those on the left like Seumas Milne, Jeremy Corbyn and Tony Benn who have been Eurosceptic, but those on Labour’s right, from Attlee through Gaitskell to Barbara Castle, Peter Shore, Gisela Stuart, Maurice Glasman and (lost sheep though he was) David Owen.

People have voted repeatedly for change – in 2010, and then with increasing force in 2016, 2019 and 2024. They want a move away from an economics that favours the rich and an immigration policy that hurts the poor. It’s been noted extensively elsewhere what the government prioritised in this week’s ‘reset’ with Brussels – shorter airport queues for business travellers and Erasmus scholarships for top graduates – and who they let down – our already declining coastal towns. But what has scarcely been acknowledged is the path never taken, the potential use of Brexit powers by a government of the left to invest more in state capacity, support nascent industries, protect critical manufacturing interests, restrict reliance on cheap foreign labour, remove VAT on fuel and shift power away from distant bureaucracies to local communities.

The Vote Leave campaign was not a crusade for greater globalisation but a plea to put our own house in order

The fault, however, lies at least as much with past Tory governments, and me, as it does with this Labour government and the PM. We defined Brexit success in a way which the people who voted for it did not recognise. The Vote Leave campaign, which I helped lead, was not a crusade for greater globalisation but a plea to put our own house back in order. During the referendum, we deliberately avoided mentioning trade and instead argued for using EU funds for the NHS, more state investment in science and greater economic equality across the country.

But the Conservative governments in which I served moved only fitfully and marginally in those directions. Brexit success became measured by the number of trade deals secured. Flawed agreements with Australia and New Zealand, which undermined domestic agriculture, were heralded as Brexit ‘wins’. And so a narrative was written in which racking up signatures from foreign leaders on any old agreement was a triumph, while we failed to address the continued decline of manufacturing. Starmer can happily accuse the Tories of inconsistency and hypocrisy in opposing his own inadequate deals, because we are compromised by our own.

I recognise that I may now sound even more like my old comrade Seumas Milne than feels comfortable. I seem to be whingeing that Brexit, like communism, hasn’t really failed – it just hasn’t been implemented properly. But let me offer a prediction.

This week’s agreement with the EU isn’t so much a reversal of Brexit as a refusal to understand why it happened. And unless people get what they voted for in 2016 – a fundamental shift in how our economy works to better serve undervalued communities, investment in the industries which give people decent wages and dignity, an end to imported labour depressing wages, action to revive tired high streets, power moving from the lanyard classes to the working classes – then there will be another, perhaps even more wrenching, vote for change. Will Keir Starmer see it coming, or will he be left once more staring blankly into the middle distance?

Does Labour need to learn to love Brexit? Michael Gove on the latest Coffee House Shots episode:

Comments