Naples is ‘certainly the most disgusting place in Europe’, judged John Ruskin. The boisterous yelling in the corridor-like streets and beetling humanity filled the Victorian sage with loathing. (‘See Naples and die’ became for Ruskin ‘See Naples and run away’.) In the city’s obscure exuberance of life he could see only a great sleaze. Naples still has a bad name. Tourists tend to hurry on through to visit the dead cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, or jet-set Capri, renowned for the debauched excesses of Tiberius. Naples may lack the monumental grandeur of Rome, but visiting it constituted the gracious end to the Grand Tour during the 17th and 18th centuries. Naples, one-time Arcady of Bourbon kings and queens, has seen better days.

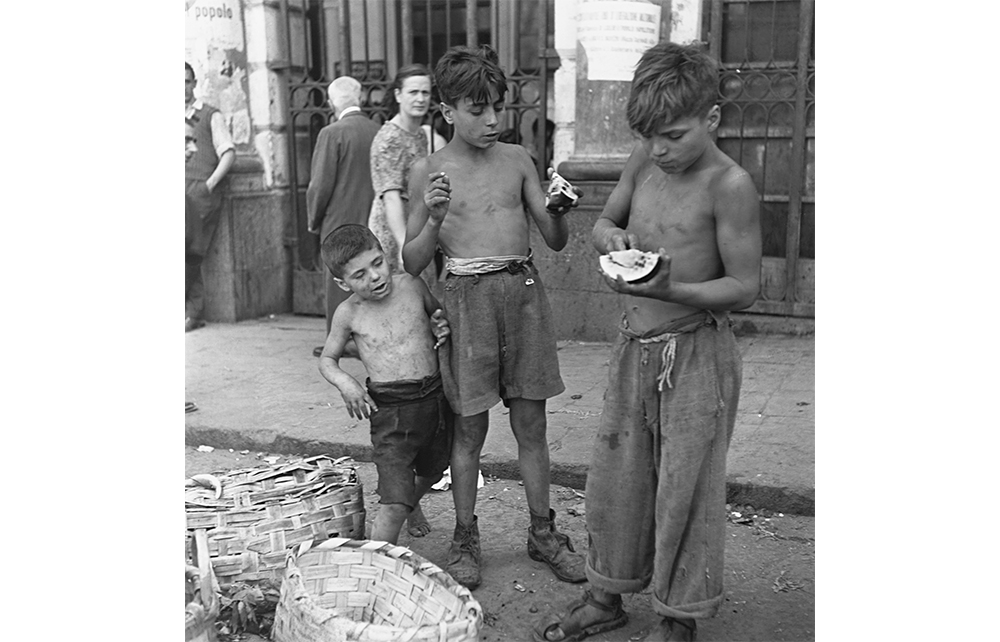

Barefoot scugnizzi hawked everything from contraband cigarettes to their own sisters

When the Allies arrived in the city in late 1943 in the wake of the German retreat they found a shell-pocked architectural magnificence shadowed by pickpocketing crime and downright miseria. The spectacle of child prostitutes and urchins on the make shocked many British soldiers. Norman Lewis was a military intelligence officer stationed there at the time. Naples ’44, his revered diary-memoir, evoked a Mediterranean outpost maudlin with nostalgia for the mandolin and the knife. Though he often embellished or transmuted his impressions into something approaching semi-fiction (only Lewis could convey so vividly the heady liquid softness of a Neapolitan evening or the tatterdemalion allure of the city’s Spanish Quarter), his book remains the great journalistic account of Neapolitan suffering and survival in wartime.

Naples 1944, Keith Lowe’s history of the nine-month Allied stewardship of the city, quotes Lewis and shares his indignation at the presence of underage prostitutes and other black-market depredations. But, unlike Lewis, Lowe is at pains to distinguish truth from invention. One of the abiding myths of Allied-occupied Naples is that tropical and other fish from the municipal aquarium were boiled up in a variety of pasta dishes, owing to food shortages. Contemporary Allied news-papers show the story to be untrue, says Lowe: the aquarium charged soldier-tourists 20 lire to admire the marine species (among them, presumably, the giant turtle which had been nosing round its tank since 1928).

Lowe, a British historian, has uncovered a wealth of previously unpublished military police reports and diary accounts. Naples 1944 is advertised as the first substantial history of the wartime city to appear in the English language. In the tangled wreckage of the city Lowe sees a reflection of the moral and material ruins of fascism. Mussolini had entered into a catastrophic alliance with Hitler following the Armistice of September 1943. Nazi Germany’s short-lived tenancy of Naples was barbarous as well as spitefully vindictive. In three weeks of vandalism, the National Library was set ablaze, large parts of the port detonated and Neapolitan men seized by the thousand for use as slave labour in the Greater Reich. In the legendary ‘Four Days of Naples’, the city rose up in protest and hounded the Germans out. For Lowe this was one of the ‘most remarkable’ (if still least known) acts of heroism of the second world war.

In occasionally repetitive pages (do publishers no longer employ copy editors?), Lowe brings Naples and its oppressed citizenry to life. The Galleria Umberto, a Victorian-era arcade, functioned as a hive of shady commerce as well as a sexual trysting place. Allied bombs had collapsed the glass skylight, but beneath its shattered dome card-sharps worked alongside Camorra gangland chancers to filch cash and rations. Italian Red Cross volunteers were assailed on all sides by the wolf-whistling of US servicemen and sex-hungry Neapolitan youth. In the winter of 1943-4, ‘Naples was probably the worst governed city in the western world’, judged one AGM (Allied Military Government) officer. Even so, the Allies managed to reinstate some kind of law and order after the Wehrmacht, in a Furor Teutonicus, blew up power plants and water supplies.

Lowe, who wrote a bestselling history of post-Hitler Europe, Savage Continent, portrays the sleazy chaos as Naples struggled to function. Along Corso Umberto I, an unlovely boulevard ploughed through the city slums after the cholera outbreak of 1884, barefoot scugnizzi (ragamuffins) hawked everything from contraband cigarettes to their own sisters. (One American soldier got so sick of being propositioned by child pimps that he hung a sign round his neck with the word ‘NO’ on it.) Dreadfully, cholera returned in 1944 to ravage the over-populated Spanish Quarter, where the streets are still so cramped that they seem barely to admit the light of day (and ‘where the sun does not enter’, goes the Neapolitan adage, ‘the doctors does’.) How the bombed-out city induced a state of blissful intoxicated self-forgetfulness in some Allied soldiery is a mystery. Naples 1944, a wonderful, valuable document, is the beginning of wisdom in these things.

Comments