I’m standing alongside Angela Rosengart, in a room full of portraits Picasso drew of her, when something spooky happens. Out of the corner of my eye, the old woman beside me becomes the young woman on the wall. It’s over in an instant, but it’s still strange and rather wonderful. For a moment, Frau Rosengart is young again, just as Picasso saw her.

We’re in the Rosengart Museum in Lucerne, a grand neoclassical building (formerly a branch of the Swiss National Bank) that houses Rosengart’s extraordinary art collection — more than 100 works by Klee, plus dozens of other modern masters: Léger, Kandinsky, Modigliani…Yet it’s her Picassos (32 paintings, plus about 100 other artworks) that really arrest the eye, for this collection is also a record of a unique friendship that lasted more than 20 years.

Angela’s father Siegfried was an art dealer, with his own gallery in Lucerne. Angela was his only child. In 1937, Siegfried acquired a still-life by Cézanne and became too fond of it to sell it. From then on, he became a collector, too. When Angela was 13 she ‘woke up’ to art, and when she was 16 she started working for her father. It was then that the Rosengart Collection really began to grow. ‘I suggested many times we should keep things, and my father agreed,’ she says, with a cheeky grin. Clearly, she was the apple of his eye.

Her mother preferred the Impressionists they hung at home but her father’s tastes were more modern, and in 1949 he took her to Paris to visit Picasso at his studio. ‘Picasso liked my father,’ says Angela. ‘My father had charisma. He wasn’t a good-looking man — one couldn’t say that — but everybody was attracted to him. He had a very good eye for quality, and all the painters appreciated that.’ Yet for his 17-year-old daughter meeting such a star was overwhelming. ‘Everybody knew the name Picasso,’ she says. ‘I was so impressed that I couldn’t utter a word!’ Picasso was nearly 70, but his lust for life endured. ‘You have a beautiful daughter,’ he told Siegfried. ‘It was the first time a man had paid me a compliment,’ recalled Angela. ‘I was thrilled.’

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the Rosengarts visited Picasso every year, in the south of France, to buy his latest paintings. ‘It was always something special when he was in the mood to show us what he’d done the day before.’ As her father’s apprentice and then his colleague, Angela was always at his side (‘Have you divorced your daughter?’ asked a friend, when he encountered Siegfried without her). Between 1956 and 1971, they mounted eight Picasso shows. She visited him dozens of times, and soon became more relaxed around him. ‘He had remained so simple. You knew he was the most famous artist of the century, but he never gave you that feeling.’ Indeed, he suffered from the same doubts as any artist. ‘There is nothing as frightening for a painter as to stand in front of an empty canvas,’ he told her.

She met Miró, Matisse, Braque and Chagall, but none of them had the same impact. ‘There’s no doubt that Picasso was the most exciting, and each of these meetings was extraordinary. It was wonderful to talk with the others, but they never made such a deep impression.’ Picasso’s aura eclipsed them all.

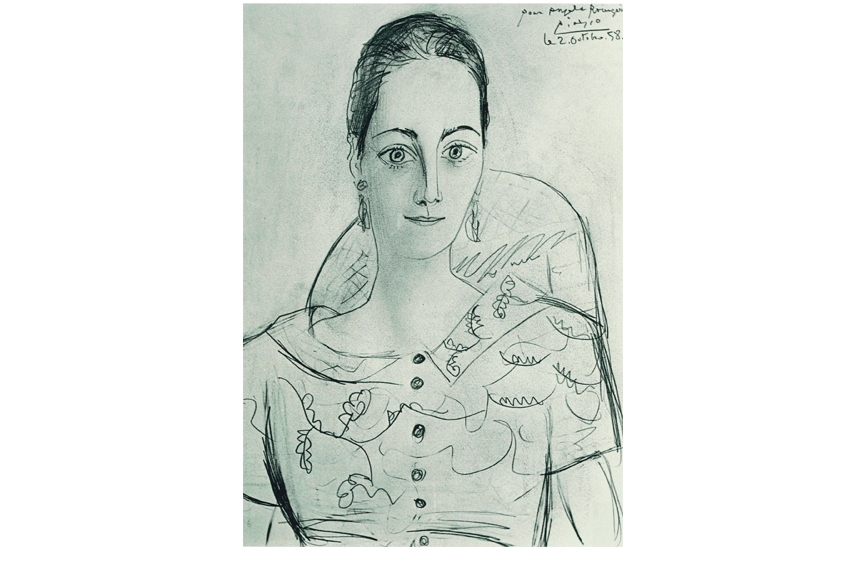

In 1954, the Rosengarts visited the artist in Vallauris, on the French Riviera. It was here, on impulse, that Picasso decided to draw Angela for the first time (if it had been her idea, she says, he would have refused). He drew her again at his villa in Cannes, and finally in his house in Mougins, where he lived until he died. The first portrait took just 20 minutes. The last one took three hours. He drew her five times, the last time in 1966. ‘I always felt burnt out afterwards,’ she says. ‘I felt he was taking everything from me.’ She says it was like an X-ray, but she found it exhilarating all the same. These five portraits, which he gave her, comprise the centrepiece of this permanent exhibition, which she opened here in 2002. They’re tucked away in an upstairs room, but there’s no doubt they’re the heart of this intimate, arresting show. Angela never married. She had no siblings and no children (‘I couldn’t have done this if I’d had children’). Her mother died in 1968, her father in 1985. This museum is her life’s work, a life devoted to fine art.

So what are they like, these portraits? How do they compare with Picasso’s other pictures, in the bigger rooms below? Standing in front of them, with Angela, they strike me as quite different from any of the Picassos I’ve seen before. Usually, Picasso is a ruthless portraitist, honing in on every blemish, but his portraits of Angela are compassionate, the sort of pictures a father might make of his own child.

In the photos Siegfried took of Picasso sketching, Angela looks shy and awkward. In Picasso’s tender drawings, she looks like a Madonna — chaste and innocent, but supremely self-assured. So why are these portraits so different? This is just a hunch, but I’d say it’s because they’re utterly platonic. ‘He was always very kind and polite to me — loving, but never aggressive,’ says Angela. There’s no carnal knowledge in these pictures, no sexual intent. ‘He only wanted to know whether my mother liked them.’ It may mean nothing, but Picasso’s childhood sweetheart was a Spanish girl called Angela.

Of course the Rosengarts’ main business was buying and selling art, not sitting for impromptu portraits, but they also bought lots of paintings they couldn’t bear to part with. ‘Sometimes, we just fell in love with a picture,’ says Angela. ‘That’s how the collection grew.’ One of their clients was especially exasperated by Siegfried’s reluctance to sell him a Picasso he coveted. Siegfried said he’d promised it to his daughter as a wedding present. Since Angela had no plans to marry, the painting didn’t belong to either of them. This frustrated collector was infuriated. ‘Then why didn’t he marry Angela?’ asked Picasso, much amused, when Siegfried told him what had happened.

That painting now has pride of place in this museum, alongside dozens of other Picassos that the Rosengarts couldn’t bring themselves to sell. ‘We never intended to make a collection,’ she says. ‘When we had a picture that we felt we couldn’t relinquish, it ended up in our house.’ Several of these paintings depict the studios where Picasso captured Angela, in pencil, linocut, charcoal and lithograph. Others portray Picasso’s second wife, Jacqueline (who became a friend), and his muse and mistress, Dora Maar. ‘He really had a special style for each of his women,’ says Angela. She neglects to mention he also had a special style for her.

‘I come here every day and look at the pictures again and sometimes get a revelation,’ she says, as we walk through her museum. She never lends to other galleries. Her collection is too personal — biography and autobiography combined. There are some fine early Picassos, but its greatest strength is its rich selection of his late, relatively underrated works, which Angela adored for their vitality. ‘No museums wanted them,’ she says. ‘They’re much more 21st century than 20th.’ These dramatic daubs are complemented by the playful sketches Picasso gave to Angela, and photos by David Douglas Duncan, showing a genius at work — and play. There are countless other treasures — M

onet, Renoir, Pissarro — but Angela’s Picassos have pride of place, rivalled only by her Klees. ‘I love Klee,’ she says, and her eyes light up like a child.

We finish our tour in front of the first work she bought, when she was 16. It’s a small drawing of a little girl, by Klee, enchanting in its simplicity. It cost her a month’s wages — 50 Swiss francs. Her Klee collection is probably the most comprehensive, but as we say goodbye the image that lingers in my mind’s eye is of Picasso’s sympathetic portraits, which transformed this timid bluestocking into a beautiful, blushing bride.

Great portraiture is a sort of sorcery, turning base metal into gold, and in this tranquil gallery, a refuge from the business bustle of Lucerne, this remarkable old woman has become an embodiment of that ancient, alchemistic art. So when she went with her father to see Picasso, did she realise she was witnessing history? ‘No,’ she says, with a nostalgic chuckle. ‘We were going to see a friend.’

The Rosengart Collection in Lucerne is open daily, including holidays. 00 41 41 220 1660; www.rosengart.ch

Comments