Scent and the Art of the pre-Raphaelites… there’s an obvious problem here: how do you represent one sense by another? Synesthesia is a neurological condition whereby some people do just that: they experience colour when they hear music, or taste words – think of the Revd Sydney Smith describing heaven as eating foie gras to the sound of trumpets. There may come a time when we get all-enveloping sensory effects when we look at paintings – an exhibition on medieval women at the British Library uses the stink of sulphur to suggest Julian of Norwich’s vision of hell and strawberry and honey for Margery Kempe’s scent of angels – but still the most obvious way of representing scent visually is by painting things that smell. And that’s the idea behind this stimulating little exhibition at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts in Birmingham.

The only clue to her unpleasant intentions is a phial of liquid, tinged violet: sniffing it would do you no good

It’s just 11 paintings and they represent a spectrum of scent, not just flowers but less agreeable sorts too. Why the pre-Raphaelites? The introduction explains: ‘With its unflinching realism and controversial spotlight on social issues, pre-Raphaelitism brought themes of stench and urban morality into the realms of “high art”. As pre-Raphaelitism transitioned into aestheticism, with its delight in beauty and sensuous pleasure, perfume was particularly appealing to artists.’ Quite the programme for a little space.

The poster image for the exhibition is Millais’s ‘The Blind Girl’ (1856) which shows a girl sitting on a grassy bank with her eyes closed, oblivious to the double rainbow behind her (see below); at her side her little sister peeps from behind the older girl’s shawl, perhaps smelling the damp wool, certainly feeling its texture. Deprived of sight, the girl can smell… what? On the bank there are harebells, the field behind the stream must have an earthy smell. On the blind girl’s lap there is an accordion, which could come in handy if the gallery ever decides to do ‘Sound and the pre-Raphaelites’.

The opening image is Evelyn de Morgan’s ‘Medea’ (1889), an odd depiction of the worst mother in history. She’s not obviously evil; serene and contemplative, with limpid blue eyes and a rose at her feet. The only clue to her unpleasant intentions regarding her husband’s new wife is a phial of liquid, tinged violet at the top; we surmise that sniffing it would do you no good. We see smoke curling out of an ornate golden box that a young girl is peeping into in John William Waterhouse’s exquisite ‘Psyche and the Golden Box’ (1903). Sleep is being released and an odour is being suggested. Indicative of the slumber that will befall her, there are white and purple poppies at her feet – unscented, I fancy. I expect the lighted oil lamp smells too.

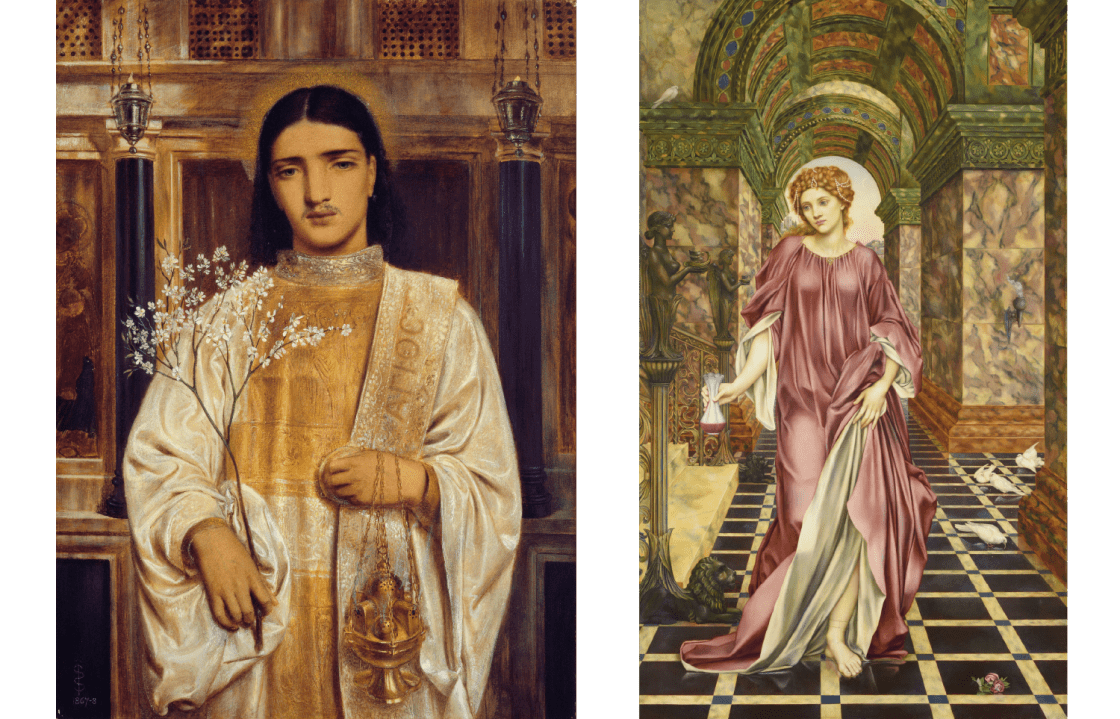

Another visitor to the underworld was Proserpina, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s depiction, painted in 1894 has an incense burner beside her, the only olfactory element in this picture of Jane Morris on which Rossetti had worked obsessively.

As for smells unpleasant, there’s an absurdly long, thin painting, ‘London Fog’, by Anna Alma-Tadema (Lawrence’s daughter) from 1906 showing a full moon over… the river? (It’s hard to tell.) We’re invited to think back to the Big Stink of half a century earlier. More subtly, Roddam Spencer Stanhope’s ‘Thoughts of the Past’ (1858-9), showing a prostitute against a river view, is very suggestive of malodorousness. But the crushed violets at her feet tell their own story about a nice country girl gone to the bad.

A more straightforward image of the pleasure of scent is Waterhouse’s ‘The Shrine’ (1895). The shrine itself is invisible; what we see is a young girl furtively sticking her nose into the roses on the altar. John Frederick Lewis’s ‘Lilium Auratum’ (1871) shows two young women in a Middle Eastern garden surrounded by roses and lilies, a charming image which the caption denounces as racialised. Really?

There are other bells and smells here. ‘A Saint of the Eastern Church’ (1868) by Simeon Solomon shows a young, barely moustachioed Greek priest holding a branch of myrtle in one hand and a censer in the other. Solomon, brought up an orthodox Jew, was homosexual and this effeminate figure would have enraged low church Victorians – not just for the cleric’s effeminacy but also his rituals.

Puig, the big Spanish fragrance manufacturers, have installed an intriguing device in the show. At the press of a button a puff of scent evocative of Solomon’s painting, as well as of ‘The Blind Girl’, is provided. One produces the aroma of incense, another fabric, the third a grassy, slightly floral, meadowy smell. The fabric one escaped me, but the other two worked. What we don’t sufficiently appreciate is that we’re living in a golden olfactory age. It is possible for scent-makers today to replicate smells on a molecular level with extraordinary exactitude. It can’t be long before fragrance is allied to art in ways this exhibition only hints at.

Comments