Kommilitonen! is Peter Maxwell Davies’s new opera, to a text by David Pountney, who also directs the première production at the Royal Academy of Music.

Kommilitonen! is Peter Maxwell Davies’s new opera, to a text by David Pountney, who also directs the première production at the Royal Academy of Music. It makes a stirring, invigorating evening, though at the end it isn’t clear which direction it is pointing in, while the whole mode of the work makes you feel that it must be pointing somewhere.

The title means ‘Fellow Students’, and there are three separate strands, which become interwoven towards the end. One is of the black American student James Meredith, who insisted on attending the University of Mississippi in 1962, and had to have massive military protection. The second is of the Weisse Rose, a student protest group in Munich who rebelled against the Nazis in 1942, and were guillotined in 1943. The third is of students in Mao’s China, who were forced to denounce their parents, and one of whom becomes a professor of history but refuses to admit what happened — that shows, says Pountney in his note, that student activists aren’t always to be sympathised with.

Maxwell Davies has written music of different styles for each thread, and they combine in a massive finale, to exhilarating effect. What is perhaps the most surprising thing about all the styles is how conservative they are, with none of the rebarbativeness that we still associate with this composer. That contributes to the sense that we are witnessing the resurrection of a forgotten German opera written in 1932 — with dates adjusted, naturally.

Yet the piece undoubtedly works, showing that with enough conviction and enthusiasm and skill what are widely regarded as outmoded idioms can, occasionally, be regenerated. A lot of the credit for that goes to the superlative quality of the RAM’s production and musical performance. Jane Glover conducts with passionate verve, and the large parts for chorus come off thrillingly. The only demanding solo vocal part is for James Meredith, sung on the evening I went by Adam Marsden, strongly and confidently, if with an irritating phoney American accent. I felt Kommilitonen! should be instantly committed to DVD, partly to show how appealing a new opera can be, partly as an advertisement for the superb establishment which mounted it.

The operatic experience of the week, and of a lot more than that, however, was English National Opera’s production at the Young Vic of Monteverdi’s penultimate surviving opera The Return of Ulysses. It goes without saying that it is updated, more or less to now. The sets, the atmosphere, even the Penelope, suggest a contemporary Antonioni movie, with her home a revolving place of chic misery. For most of the opera everything is black and white, and colour only floods the scene at the end. The opera is quite extensively cut — this is very much Monteverdi as ‘music theatre’ — but it does work wonderfully well. The cuts mean that this is much more the Patience of Penelope than the return of Ulysses.

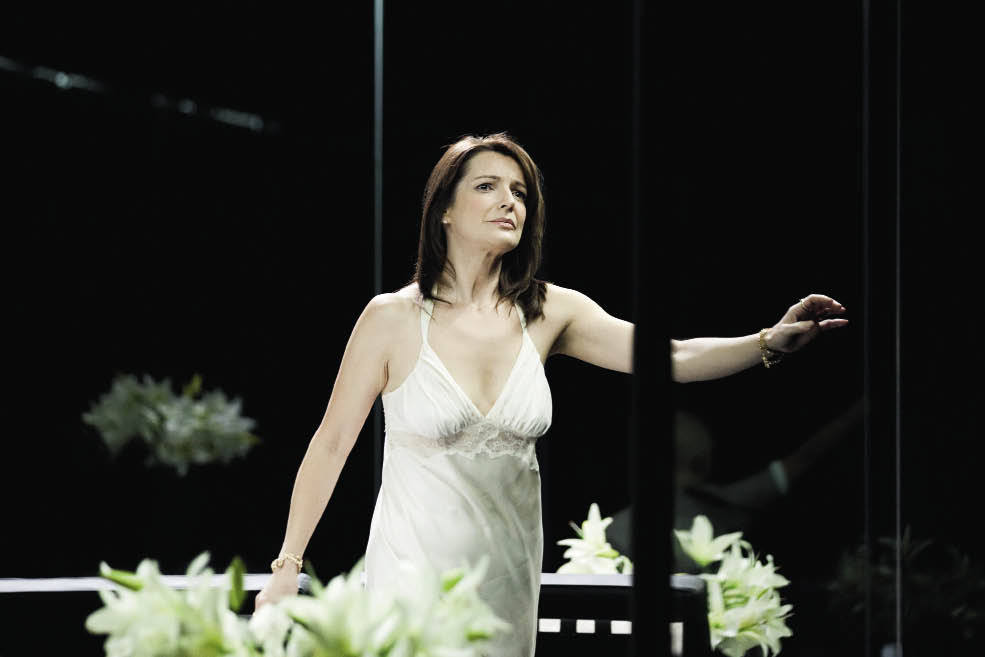

As a study in the agonies and doubts of prolonged separation, reaching the point where happiness seems like a threat, this opera has never been surpassed in any medium: it is one of the defining masterworks of the genre, and certainly one whose ending, when Penelope and Ulysses at last sing together, is almost as hard to bear for the audience as it is a relief for the protagonists. Fortunately, the pair in this production are fully up to every demand made on them — and that is a vast number — by the director Benedict Andrews. Pamela Helen Stephen is the only Penelope I can imagine — and one sees her, for much of the time, suffering in close-up on two large screens, as well as crumpled on a Barcelona chair or crawling round her apartment. She even seems, momentarily, to respond to the advances of one of the Suitors. Her lower register is almost speech-song — but that is true of a fair amount of the singing, and isn’t a criticism. There are stretches where she sings to ravishing effect.

Tom Randle has an immense gamut of emotions as Ulysses, and he, too, gives a performance which obliterates my memories of any other. In the suffering stakes, this Ulysses is at least the equal of his wife, even though he has the sublime consolation of the recognition of his son (superbly performed by Thomas Hobbs) and the victory over the Suitors, whom he dispatches with a pistol and with terrifying ruthlessness. I can’t go on, because of space, but this is one of the operatic productions I have seen which I feel anyone who says things about the medium being elitist, inaccessible, etc. should be forced to attend and report on.

I can only mention University College Opera’s latest brave rescue: Weber’s fragmentary opera The Three Pintos, completed in 1886 by Mahler. It all sounds authentically Weberian, if not of the top class. UCOpera’s performance was of a higher standard, all round, than they often achieve, and showed that this piece deserves an occasional airing — the most, it seems, that even the finest Weber is ever likely to get.

Comments