There’s no getting away from that title. I will never see the world again. It catches your eye on the bookshelf. I will never see the world again. It’s there, at the top of every page. I Will Never See the World Again. It’s a killer opening, before the book has even begun, and it’s all true.

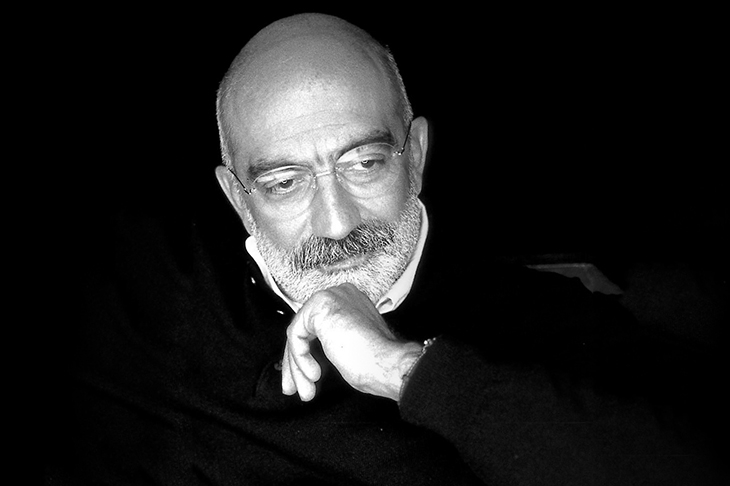

Ahmet Altan, one of Turkey’s leading writers, in 2016 was arrested on charges of providing subliminal messages to coup supporters, and has since been sentenced to life imprisonment:

Never again would I be able to kiss the woman I love, embrace my kids, meet with my friends, walk the streets. I would not have my room to write in, my machine to write with, my library to reach for. I would not be able to open a door by myself.

That’s not to say that Altan is incommunicado. He is working on the fourth book in his Ottoman Quartet in prison, and last autumn he completed a ‘20 questions’ interview with the Times Literary Supplement, though the results weren’t edifying. (Favourite new book? ‘I don’t have access to new books here. The only thing I read that was published in the last 12 months was the prison magazine. It wasn’t that interesting.’) The essays that make up this book were contained among personal notes Altan gave to his lawyers, and released one by one to his friend Yasemin Çongar, who has translated them into English.

The first essay, ‘A Single Sentence’, describes his arrest and, like the others, it’s written in short sentences and staccato paragraphs, as though each represents a thought Altan has hurried to jot down in secret. The effect of this style is to build a case, block by block, to create a solid reef by the accumulation of small, fragile ideas. When he was taken away by car, he tells us, the policeman accompanying him offered a cigarette, which Altan declined. ‘I only smoke when I am nervous.’ This simple sentence — an accidental quip — became central to his mindset in prison:

It was a sentence that put an unbridgeable distance between itself and reality. It ignored reality, ridiculed it, even as I was being transformed into a pitiful bug who could not even open the door of the car he was in.

In refusing to play the role of victim, he was able to ‘create a new reality in the mind’s safe harbour’. But this new reality still had privations, like the lack of mirrors in the police cell toilets. He looked at the wall, expecting to see himself, but ‘I wasn’t there. It was as if I had been erased from life.’

These essays often read like Altan’s therapy for himself, and it’s a pleasure to find him exploring ideas, turning them around, arguing against himself and conjuring up the reader — you, me — as a form of companionship in isolation. Perhaps it’s this that has kept his spirit intact in the face of indignities (such as seeing psychiatric patients being treated while still in handcuffs) that are, if not exactly Kafkaesque, certainly Kafka-ish. All in all, the lack of rancour in these pages is miraculous.

It would be easy to assume the value of this book purely from its subject matter —indeed, from its existence. Altan is alert to this risk: ‘Add the sentence “I write these words from a prison cell” to any narrative and you will add tension and vitality.’ But, he adds:

I am not in prison. I am a writer. I am neither where I am nor where I am not. Because, like all writers, I can pass through your walls with ease.

And so he has.

Comments