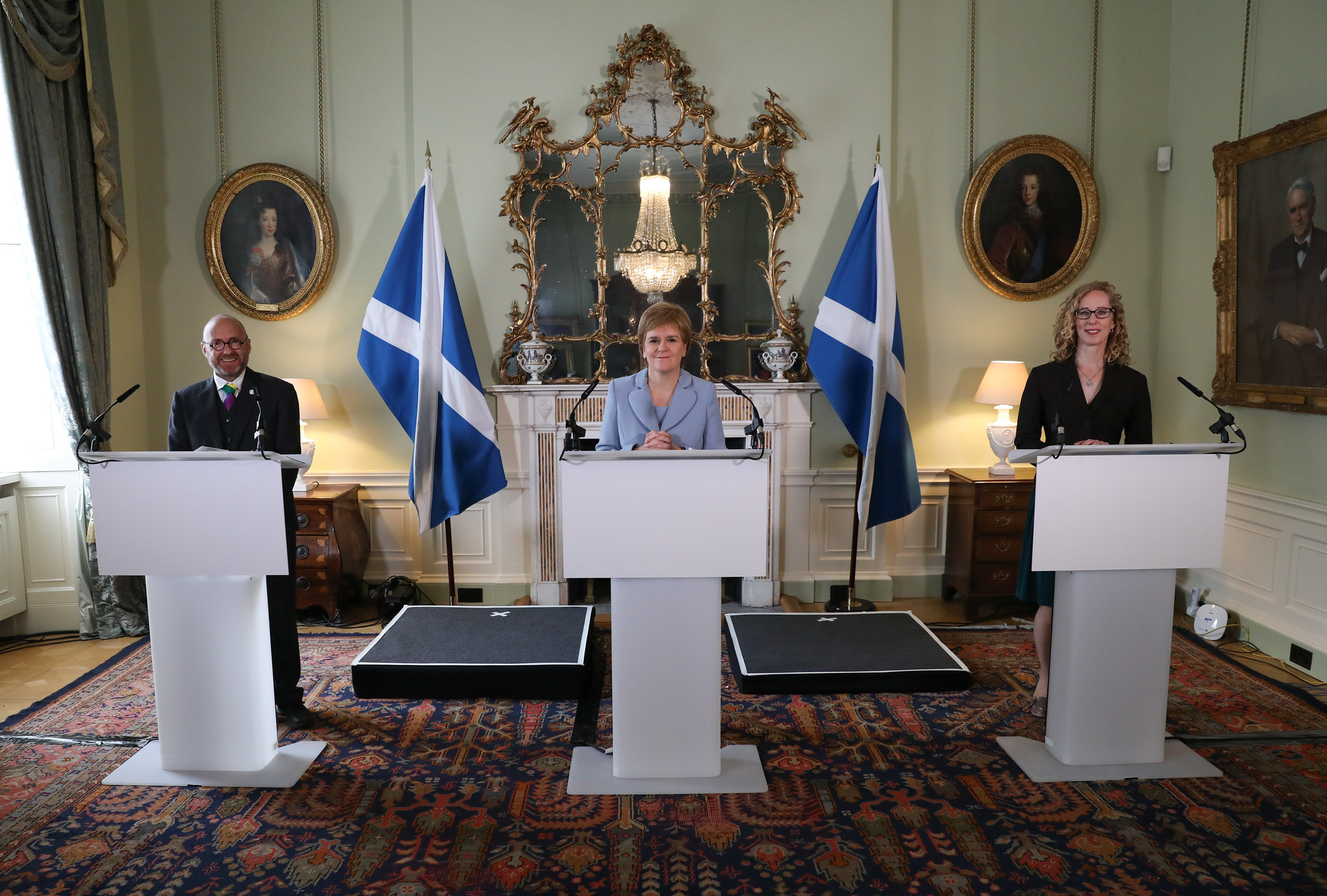

The deal struck between Nicola Sturgeon and the Scottish Greens takes Scotland’s devolved government into new territory. For one, it is the first time a Green party has been part of a ruling administration anywhere in the UK. For another, it is a different kind of governing alliance from that which we’re used to in Britain (though less so in Northern Ireland). It is not quite a full-blown coalition like the Cameron-Clegg government — the pact, published this afternoon, outlines areas where the two parties will continue to express separate positions — but nor is it a mere confidence and supply arrangement like the one Theresa May secured with Arlene Foster after the 2017 election.

Two Green MSPs will take up ministerial posts, albeit as junior ministers, and the government will pursue a joint programme. The set-up is remarkably similar to that agreed last year in New Zealand between James Shaw’s and Marama Davidson’s Green party and the minority Labour government of Jacinda Ardern, who is known to be one of Sturgeon’s political heroines.

The opposition is none-too-pleased. Scottish Labour leader Anas Sarwar forecasts ‘disaster’ while the Scottish Tories’ Douglas Ross is positively blood-curdling, calling the pact ‘a nationalist coalition of chaos focused on splitting up the country and dividing Scotland with another bitter referendum’. (That’s what I like about Douglas Ross. He makes me sound like a columnist for The National.) In one sense, the co-operation framework simply puts down in black and white a practice that has been apparent for years now, and especially since the SNP returned to minority government after the 2016 election.

Sturgeon has learnt more from David Cameron than Jacinda Ardern about how coalitions work

Patrick Harvie, one half of the Greens’ gender-balanced co-leadership (don’t ask), has never hidden the fact that his vision for the party is as a more progressive analogue of the SNP, an outfit with identity politics of the nationalist and gender varieties, rather than the environment and climate crisis, at the heart of everything it does. On Harvie’s watch, the Greens have come to be seen as a mere adjunct of Sturgeon’s party, a patch of political territory the Nationalists see as their own. In signing up to a unity government, Harvie has abandoned any pretence that his is an autonomous party. The SNP is Russia, the Greens are Crimea, and they’ve just been annexed.

The not-a-coalition agreement pledges a second referendum on independence within the next five years. The argument will be that the SNP and Greens combined won a mandate in May’s Holyrood election for another constitutional vote. While it can be difficult to discern from one week to the next what Downing Street’s position is on Scotland, Boris Johnson can point out that it is impossible to achieve a mandate at a devolved election for the exercise of a reserved power. Or he could just keep saying no. The SNP has previously threatened to ignore him and press ahead with a referendum, in effect daring Whitehall to take the Scottish government to court. But it’s a high-risk strategy and one with no guarantee of success.

This is, in part, what the yellow-green buddy-up is about. Sturgeon imagines herself as the Ayrshire Ardern but the New Zealand PM cut a deal because she was impatient to implement a developed and defined political agenda, Sturgeon’s tribute act has more to do with avoiding action. Folding the Greens into her government takes an entire opposition party out of the picture, gives the SNP a partner in crime with whom the blame for failings can be shared and silences the potential for criticism from the pro-independence left. Sturgeon has learnt more from David Cameron than Jacinda Ardern about how coalitions work: the dominant party gets stability and the junior partner gets the flack.

Sturgeon is many things but daft isn’t one of them. She knows another referendum on secession is probably off the cards at least until the Tories are dislodged from Downing Street. Implicating the Greens as an accessory to her government’s main policies not only insulates Sturgeon from internal criticism that she has failed to deliver a referendum but tarnishes Harvie’s party with that failure so it cannot gain electorally from SNP supporters scunnered at being marched up the hill and back down again one too many times.

As such, this deal is something of a political masterstroke from Sturgeon, though if Scotland had a more adversarial media she would be facing questions about the doubtful things her new best pals have said and done over the years. For the Greens themselves, they risk becoming human shields for Sturgeon and, in the process, being seen as sell-outs by the left. The BBC’s Phil Sim points out that the two parties are ‘largely aligned on income tax’ but this is only because the Greens have conceded that ‘now is not is not the time for increases’ for most Scots. The pandemic has forced parties of all ideological stripes to rethink core beliefs but this is an outfit that went into the 2016 election pledging a top income tax rate of 60 per cent. If the Greens reckon a global health crisis that has thrown inequalities into sharp relief is not the time to push for a more progressive tax system, progressives might wonder if it’s time to find another party.

One thing the Greens are likely to get out of their new relationship with the Scottish government is progress on one of their top priorities: gender identity. Harvie’s team are the full Judith Butler on these matters. In the last parliament, they voted against giving sexual assault victims the right to request a forensic examiner of the same sex rather than the same ‘gender’. Sturgeon is fixated on these matters too, which gives the gender ideologues real scope to press ahead with their agenda. In fact, the Greens don’t disagree with the SNP on all that much. The co-operation document lists Nato, prostitution and private schools but for the most part the Greens are simply the SNP without the endless triangulations.

Of course, they will have to start doing some triangulating of their own now they’re to be in government and the fallout will be fascinating to observe. Perhaps no one will be watching closer than Alex Cole-Hamilton, confirmed this afternoon as the new leader of the Scottish Liberal Democrats. If he is able, over time, to tag the Greens with the Scottish government’s bold-rhetoric-lame-results record on climate and the environment, there could be an opportunity for him to begin peeling away the sort of well-heeled, socially conscious, eco-fretting voters the Greens have come to rely on. If Harvie can be more Nat than the Nats, there is no reason Cole-Hamilton couldn’t make his party more green than the Greens.

This deal is canny strategy from Sturgeon, a big gamble for the Greens and gives the opposition a whole new government to get stuck in about.

Comments