When it comes to making the case for removing Scotland from its most important trading bloc, Nicola Sturgeon takes her lines directly from the Brexiteer playbook. Asked about the possibility of a post-independence hard border between Scotland and England, Sturgeon’s standard response has been to tell people what she would want instead of the reality of what would be.

Just as Brexiteers started off under the delusion that both frictionless trade with the EU and the freedom to trade on UK terms with the rest of the world was what they wanted and was achievable, so too Sturgeon liked to suggest she was aiming for an independent Scotland with all the benefits of open trading relationships to EU and remaining UK markets. Now that the terms of the EU-UK trade deal are established, however, that line is no longer tenable.

As outlined in a new report from the Institute for Government, the border realities of Scotland leaving the UK, particularly if Scotland then joined the EU, are dramatic. ‘After more than three centuries as part of a single market, Scotland and England would find themselves on either side of a hard economic border,’ says the report.

The sight of a physical border being erected between Scotland and England would come as a shock to many Scots.

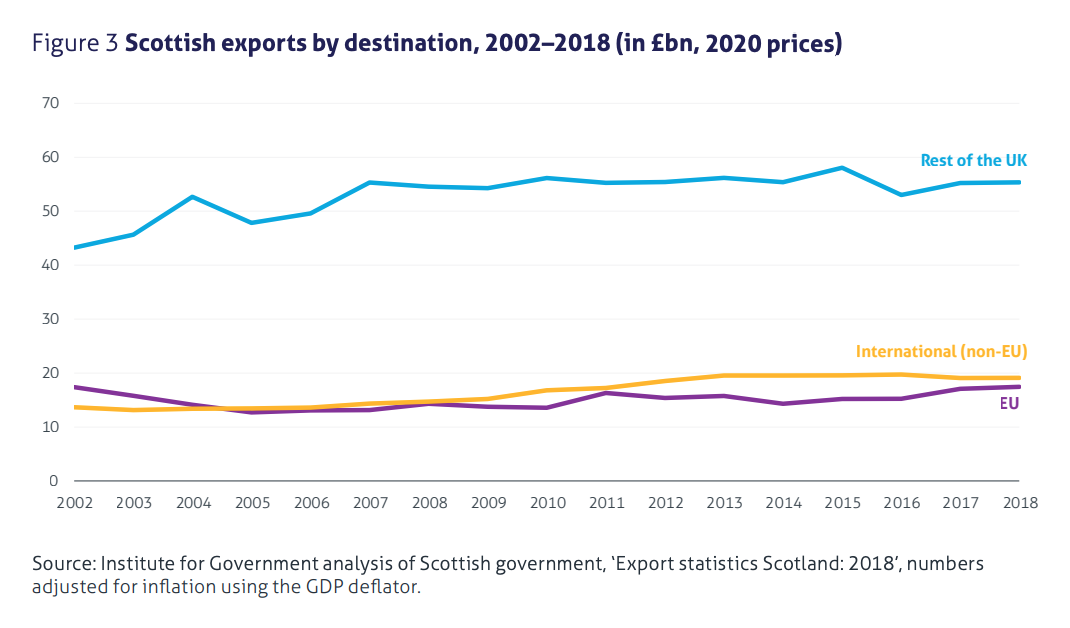

If an independent Scotland were in the EU then trade between Scotland and England/Wales would be governed by the terms of the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), which came into effect at the start of the year. Scottish exports to the rest of the UK are worth three times as much as exports to the EU, as the the Institute for Government’s chart below shows. An independent Scotland entering the EU would suddenly find a big chunk of its exports subject to trade barriers.

The Anglo-Scottish border would become a new external customs and regulatory frontier for the EU. Scotland would have to enforce the EU’s customs processes and implement regulatory checks on goods such as animal and plant products. For example, products of animal origin would have to be accompanied by an export health certificate signed by a vet. These currently cost between £50 and £175 per certificate. VAT processes and rules of origin requirements would create more barriers to trade and costs for businesses. Physical border infrastructure would be required.

Whether or not there would be free movement of people is an open question. To remain outside the Schengen Area of European free travel and within a British Isles Common Travel Area, which Ireland and the UK currently form, Scotland would have to secure a special opt-out as part of its EU entry agreement. The Institute for Government says it is conceivable Scotland could get this, but there are no guarantees.

If Scotland were part of Schengen, then entry and exit checks on people entering Scotland from the remaining UK would be required. A grandmother from Coventry visiting her nephews in Glasgow would have to get her passport stamped at a border checkpoint before entering the country.

The land border between Scotland and the rest of the UK extends approximately 154 kilometres, from Lamberton on the east coast to the Solway Firth in the west. The border is crossed by 21 roads and two railway lines. A significant amount of infrastructure would therefore have to be put in place to create the new EU external border.

And even if Scotland did not go for EU membership but instead something lesser, such as joining the European Economic Area (EEA), which grants access to the single market while being outside the customs union, barriers to trade across the Anglo-Scottish border would still be an issue. Extensive checks and paperwork on agri-foods for instance would be required.

The sight of a physical border being erected between Scotland and England — the fences going up, the new motorway sidings and customs blocks being built at Gretna — would no doubt come as a shock to many Scots. For a nurse living in Annan who works in a Cumbrian hospital, or a north Northumbrian family who send their kids to school just over the border, it could be life-changing.

Nicola Sturgeon might well say the fences and the border controls are not something she wants to see, but they would be an inevitable outcome of her separation policy. Just as those who advocated the UK leaving the EU single market and customs union have to take ownership of the difficulties exporters now face, so too Sturgeon has to take ownership of what she advocates.

And the outcome of that is now clear: the harsh reality of a hard border cutting its way across the island of Britain for the first time in hundreds of years.

Comments