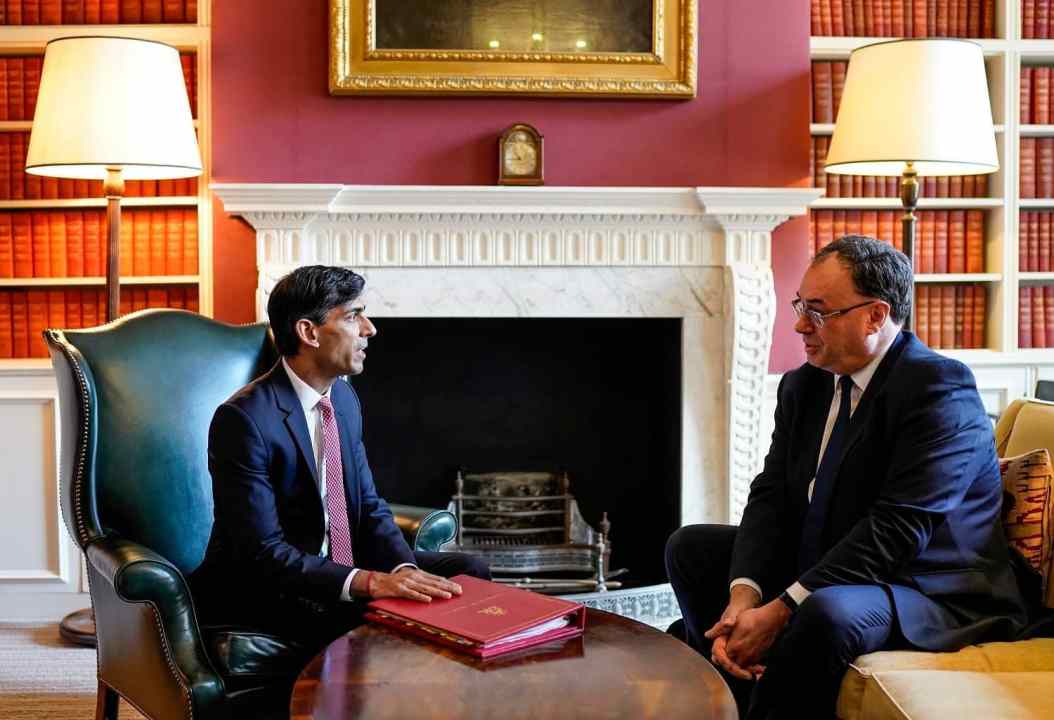

Inflation has hit a 40-year high. The cost of household utilities rose by an average of £700 last month. We are now facing inflation of 9 per cent and the figure is still careering upwards. In response, politicians and ministers have attacked the Bank of England. Some commentators have even started to call for Governor Andrew Bailey to resign. The Governor himself and Chancellor Rishi Sunak say there is nothing that can be done about prices rising. They’re both wrong.

First, let’s understand why it is unfair to attack the Bank of England. Under our system, the Bank is not independent, as some like to claim. Rather, it has what is called ‘operational independence’. That means that the rate of inflation is the responsibility of the Chancellor of the Exchequer but how that rate is achieved operationally – through a blend of interest rate rises, money-printing or intervention in foreign exchange markets – is a matter for the Bank of England.

Under our system, the Bank is not independent, as some like to claim

To understand the concept of operational independence a bit better, imagine that Transport Secretary Grant Shapps decided to build a new road. He’d instruct the relevant officials to arrange the construction and give them a budget. But he presumably wouldn’t arrange the hiring of a construction company to build it. Or when Defence Secretary Ben Wallace decided the UK would supply arms to Ukraine, he presumably didn’t personally schedule which planes would carry the munitions or what time they landed.

In both cases, such operational matters are for officials to manage. And it’s the same for monetary policy. The actual execution of the policy is a matter for the Bank of England to arrange. But in none of these cases – neither the road nor the weapons nor the rate of inflation – is it true that the government minister is not responsible for the policy decision.

The rate of inflation is chosen by Rishi Sunak. If it doesn’t happen – if the target isn’t met – we should hold him just as accountable as we would hold Shapps if the road wasn’t built or Wallace if the weapons weren’t delivered. If it didn’t happen, in each case we’d expect the minister responsible to chase the matter and hold the failing bureaucrats to account.

Yet since 2007, when the inflation target was first missed, the message to the Bank of England from chancellors of all political stripes has been that this doesn’t matter. Thirty letters have been written by Bank of England governors explaining why they missed their targets. Not once has a chancellor admonished them or sought to enforce the target in any way. The Bank has had every reason, therefore, to believe that the inflation target is entirely notional, the management of inflation is entirely up to the Bank, and it can deliver whatever inflation rate it sees fit. In particular, if it believes inflationary pressures are transitory – so they’ll be gone in a couple of years – it doesn’t matter what inflation is in the meantime.

Since that is the message chancellors have given to the Bank for the last 15 years, it is hardly reasonable for politicians to suddenly start demanding the Governor’s resignation now. How was the Bank to know that politicians would suddenly change their mind and decide that missing the target mattered this time when it never has before?

Sunak and Bailey are wrong to say inflation is beyond their control. Only about a third of the current inflation spike is down to energy prices and other central banks (for example in Switzerland) are not seeing the inflation rise as we have. But even if all of the price rises were down to energy that would still not mean it could not be controlled. Inflation in the 1970s was heavily driven by oil price rises, but no one thinks that means the UK was powerless to prevent inflation from going above 20 per cent as it did. The German Bundesbank refused to accommodate the price rises, kept inflation down at a short-term economic cost and in the process built up a credibility that was central to West Germany’s economic success in the 1980s.

Perhaps it wouldn’t have been right for the UK to fight inflation this time. But that’s a matter the Chancellor should be deciding upon, not the Bank. Sunak needs to decide, now, while there is still time to do something about it, what inflation rate is acceptable for 2023 and 2024 and set the Bank credible targets that he expects them to meet and will enforce.

People say Sunak should do other things about the cost of living – defer tax rises; impose price rise caps; limit public sector wage rises; subsidise the bills of the poor. But these are all details, secondary matters. The main thing he can and should do about the cost of living is tell the Bank what rise in the cost of living he wants it to deliver. If he fails to do that, there is little point in debating these secondary details.

Take responsibility for the inflation rate, Chancellor. It’s your call.

Comments