Whereas it is generally agreed that music has charms to soothe a savage breast, Congreve might have added that music also has the power to inflame bellicose fervour. Patrick Bade, who lectures at Christie’s Education and the London Jewish Cultural Centre, has written a commendably exhaustive history of how all sorts of music were used to strengthen civilian and military morale and to demoralise enemies immediately before and during the second world war.

The BBC radio programme Music While You Work, for example, was believed to help make British factory workers contentedly productive. Musical propaganda broadcasts were supposed to convince Germans that we were patriotically more ardently motivated than they. ‘Music wars’ of the 20th century were waged with demonstrations of high culture and popular entertainment. Every national anthem was a militant Christian proclamation of superior righteousness, strength and joy. According to Bade:

The endless stream of military marches broadcast from German radio stations was intended to induce a state of mindless obedience and aggression in the German military and civil population, particularly towards the end of the war, when authorities feared a breakdown of resolution and discipline.

Although his anti-Semitic policies forfeited any just claim to civilisation, Hitler cited Germany’s musical tradition in an attempt to assert cultural superiority. In a speech broadcast in November 1939, he asserted that: ‘One single German, shall we say Beethoven, achieved more than all the English put together.’ Of Wagner, his favourite composer, he said: ‘Whoever wants to understand National Socialist Germany must first know Wagner.’ Bade goes on to quote Woody Allen’s later response: ‘Every time I hear Wagner I feel like invading Poland.’

As it is obviously true that Germany’s classical musical heritage outweighs any other, Britain continued to perform the Germans’ music during the war and played it back to them, most notably Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, whose opening bars reminded European resistance fighters and ourselves of the morse code dot-dot-dot-dash of V for Victory. Britain’s symphony concerts and operatic performances, though fewer than the Germans’, were enriched by the talents of Jewish musicians who had left Germany as refugees.

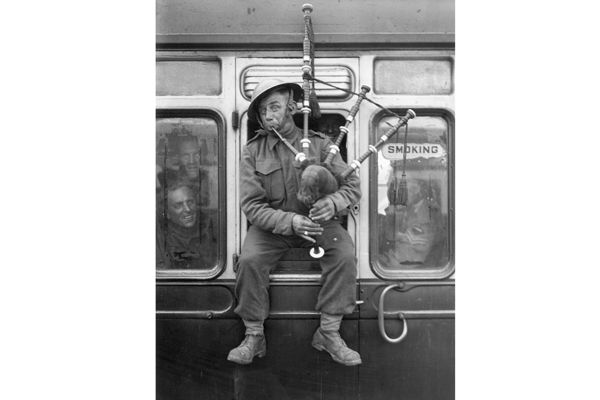

Bade devotes his most appreciative attention to high culture, but also acknowledges the important influence of popular music. As Noël Coward observed: ‘Extraordinary how potent cheap music is.’ Britain had a populist musical team of great potency, in the inherited spirit of the music hall and the palais de danse — Gracie Fields, George Formby and Vera Lynn, to name but a few. For the majority of the population, at home and in the forces, ‘The Biggest Aspidistra in the World’, ‘When I’m Cleaning Windows’ and ‘We’ll Meet Again’ were worth more than any number of foreign-language arias.

Technological developments in the 1920s and 1930s, Bade points out,

conspired to give American popular culture an unprecedented world dominance that was deplored by conservatives all over Europe and deeply feared and envied by the Nazis in particular. Swing came along at exactly the right moment, emerging from black into mainstream American popular culture in the mid 1930s through popular dance bands such as those of Benny Goodman, the Dorsey Brothers, Count Basie and Glenn Miller, and crossing the Atlantic towards the end of the decade.

As early as 1935, Nazi officials attempted to ban American jazz, a public relations exercise rather like trying to hold back a tidal wave with a sieve. That year, Bade writes,

the programme director of the German broadcasting company, announced: ‘We mean to eradicate every trace of putrefying elements that remain in our light entertainment and dance music. As of today, Nigger jazz is finally switched off the German radio.’

During the 1940s, however, though Nazi authorities looked for signs of subversive Kulturbolschewismus, some German bands continued to imitate American style, while in occupied France: ‘Swing rebels were known as “Zazous” a term ultimately derived from the scatting of the black American performer Cab Calloway.’

There’s an entertaining chapter on ‘War Songs: Humorous, Patriotic and Military’. Bade allows himself to reproduce the ‘scurrilous, earthy vulgarity’ of possibly the most effectively derisive anti-Nazi lyrics of all:

Hitler has only got one ball Göring has two but his are small Himmler’s are very sim’ler And Goebbels’ got no balls at all. How could we fail to win?

Comments